Lucien refuted: 'Religious Liberty: Illusory Distinction, Unwarranted Conclusion'

Abbé Bernard Lucien's defence of Vatican II's new doctrine of religious liberty recently appeared in English. But his claims were already refuted years ago by his former colleague, Abbé Hervé Belmont.

Abbé Bernard Lucien's defence of Vatican II's new doctrine of religious liberty recently appeared in English. But they were already refuted years ago by Lucien's former colleague, Abbé Hervé Belmont.

Editors’ Notes

(WM Review) – Less than a month ago, Abbé Bernard Lucien's essays on Vatican II’s doctrine of religious liberty appeared in English translation. These essays have attracted interest from those attempting to reconcile the Council’s teaching with that of the Church’s tradition.

This effort to “square the circle” rests on a contrived distinction that runs contrary to the Vatican’s own interpretation and implementation of the Council’s teaching on religious liberty.

What follows is the refutation of Lucien’s “solution,” written at the time of his departure by his long-term collaborator Abbé Hervé Belmont. It originally appeared in the review Didasco, and was reproduced in French online in 2005.1

About Abbé Lucien

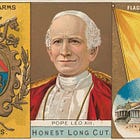

Abbé Lucien entered Archbishop Lefebvre’s seminary in 1972. Though he left in 1977 due to his adherence to then-Fr Guérard des Lauriers’s sedeprivationist thesis (the “Cassiciacum thesis”), Archbishop Lefebvre nonetheless ordained him in 1978.

He and Belmont became leading proponents of the thesis, co-editing Les Cahiers de Cassiciacum and co-authoring La Liberté religieuse, which demonstrated the radical contradiction between the traditional magisterium and Vatican II.

In the early 1990s, however, Lucien abandoned this position, claiming that there was only an apparent contradiction between the old and new doctrines on religious liberty. In 1992, he retracted some of his former positions, aligned himself with the post-conciliar hierarchy—in whose institutions he now teaches.

His reversal was all the more startling given his prior denunciations of similar capitulations—some of which are reproduced in Belmont’s refutation below.

But before we proceed to that, let us note that the new translation of Lucien’s work is preceded by some regrettable editorialising in the Translator’s Note by John Pepino, and the Foreword by Alan Fimister.

We will address these claims in a separate article.

Disclaimer

We have published several articles by Abbé Belmont in the past, and value his writing highly.

For the sake of clarity, we must note that parts of this refutation are based on a defence of Bishop Guérard des Lauriers’s “Cassiciacum thesis,” to which we do not adhere.

However, we agree with much of the argumentation which its proponents tend to employ—especially its “deductive argument,” that Vatican II and its aftermath imply that those promulgating such doctrines cannot be true popes. We have developed this argument along lines that do not lead to the materialiter/formaliter distinction elsewhere.

SDWr.

Religious Liberty: An Illusory Distinction, an Unwarranted Conclusion

Abbé Hervé Belmont

Texts from Dignitatis Humanae are generally from Michael Pakaluk’s translation. Page numbers indicated in the text are from Belmont; in the footnotes they are from English translation.

Comments made in 2005

Several messages have mentioned Abbé Bernard Lucien and the fact that he changed his mind regarding religious liberty and the situation of the Church.

Abbé Lucien was a friend to me (and remains so in corde meo) and a master, both in intelligence (which the good God granted him in great measure and depth) and in the fight. His change of position was a painful episode for me—God alone knows how much—just as were the episcopal consecration of Fr Guérard des Lauriers2 (may God rest his soul), and the reversal of Fr de Blignières and his community.

This mention gave me the idea of reproducing below the article I had written in the valiant review Didasco to try to explain why I could not follow Abbé Lucien.3

Introduction

After the publication of several works of clear and vigorous doctrine dedicated to the defence and application of the Catholic faith in our times of crisis and apostasy, M. l’Abbé Bernard Lucien has now effected a radical change of direction.

He publicly declares, in fact, that he is now convinced there is no contradiction between the Catholic doctrine condemning religious liberty—that is, condemning the claim that every man has a civil right to religious liberty—and the teaching of Vatican II affirming the existence of such a right. He declares, consequently, that he no longer adheres to the “Cassiciacum thesis,” a thesis according to which the Catholic Church is at present deprived of the authority of the Sovereign Pontiff and of all that follows therefrom, the material continuity of the hierarchy being preserved. He therefore acknowledges the pontifical authority of John Paul II and the doctrinal authority of Vatican II.

This second point is merely alluded to without detail, whereas the first is somewhat developed. Abbé Lucien appeals here to the distinction between acting according to one’s conscience and acting as one pleases: according to him, while Gregory XVI and Pius IX condemn those who affirm the existence of a right to act (in religious matters) as one pleases, Vatican II merely teaches the right to act according to one’s conscience; there would therefore be no contradiction.

If one wishes to examine this new position, two questions must be asked:

Is it true that the distinction proposed by Abbé Lucien resolves the contradiction?

Does it follow that the “Cassiciacum thesis” can no longer be considered true, as the adequate explanation of the Catholic Church’s situation since Vatican II?

If the answer to even one of these two questions is in the negative, one must refuse to follow Abbé Lucien along the new path he is taking.

1. The crisis of the Church is not reducible to the single question of religious liberty

The second question is not a new one. When Father de Blignières and the Saint Thomas Aquinas priory made, in 1987–1988, the same about-turn as Abbé Lucien has today, the latter drafted an initial refutation for which he had asked me to provide an introduction. This introduction recalled that the crisis of the Church cannot be reduced to the sole question of religious liberty, and that the “Cassiciacum thesis,” which seeks to analyse this crisis in the light of faith, is founded neither solely nor even primarily upon the contradiction of religious liberty. Abbé Lucien, in the epilogue of his work, adopted this view as his own. It is all the more surprising, then, to see him now taking the opposite stance, given that, from the point of view of the faith, nothing has fundamentally changed over the past four years. We here reproduce this introduction, and Abbé Lucien’s epilogue.

‘Introduction’

In a letter titled “News from the Society of Saint Thomas Aquinas” (Winter 1988), Father Louis-Marie de Blignières announces the change of direction recently undertaken by the Saint Thomas Aquinas priory.

Here is how this announcement may be summarised:

“Our research has convinced us that there is no contradiction between the teaching of Vatican II on religious liberty on the one hand, and the condemnations issued by the popes of the last century against freedom of conscience and of worship on the other.

“Consequently, we no longer adhere to the ‘Cassiciacum Thesis’ – which asserts that the Church is currently deprived of the Authority of the Sovereign Pontiff and of all that follows therefrom, the material permanence of the hierarchy being preserved – and we therefore recognise the pontifical authority of John Paul II and the doctrinal authority of the Second Vatican Council.”

Abbé Bernard Lucien will presently analyse the argumentation that attempts to demonstrate the absence of contradiction; this argumentation – which, in fact, brings forth no truly new element – is merely outlined in the letter under discussion here: it is developed in a pamphlet by Brother Dominique-Marie of Saint-Laumer included in the same mailing.

The purpose of this introduction is to recall that the question of the crisis in the Church and of the state of authority cannot be reduced to the single issue of religious liberty, which is but one element—albeit a very important one—of a much broader whole.

One remains astonished that the new conviction of the religious of Chémeré regarding religious liberty should call into question their analysis of the state of authority in the Church; such intellectual fragility might raise the suspicion that they had never truly adhered to the “Cassiciacum thesis”, or at least had retained from it only an intellectual framework that collapsed once their conviction changed. But reality itself, alas, does not change as swiftly as the mind of a Dominican. And since it is upon this reality—observed and theologically analysed—that the said “Cassiciacum thesis” is founded, there is no objective reason to call it into question.

The reality is that the Christian people, as a whole,4 have lost the faith. Certainly, God alone searches the reins and the hearts, but it is observable and certain that the majority of Christians no longer profess the faith of the Church—neither in their way of life, nor in their words when asked about their assent to one or another truth belonging to the revealed deposit [of faith].

The reality is that this “apostasie immannente,”5 to use Maritain’s expression, was willed by those who ought to have prevented it and who, on the contrary, first laid down the causes of it, and then—once the effects became visible—persisted in maintaining them. Certainly, the present state of the world and the techniques of subjugation to reigning ideologies that corrupt the faith do not make the Christian life easy. But it is precisely towards that world that Christians were pushed by the hierarchy and in the spirit of Vatican II. They remained defenceless, abandoned, deprived of the teaching of Catholic doctrine—disfigured as it was by many catechisms and sermons, in the face of the unbridled onslaught of heresy, which found much open and official complicity within the Church.

The reality is a liturgical reform infested with the spirit of Protestantism; a reform that is neither the fruit nor the expression of the Church’s faith; a reform that causes the Christian people to lose the sense of the infinite holiness of God by eliminating the outward signs of adoration and by diverting the liturgy towards the “cult of man”.

The reality is that the doctrine of religious liberty is not an isolated accident within an otherwise irreproachable exposition of Catholic doctrine, nor a harmless misstep that appeared by chance in a clear sky and was quickly forgotten. Religious liberty lies at the origin of the betrayal of the last Catholic states; it stands at the heart of the Church’s alignment with the world; it is a doctrine in perfect resonance with the scandalous and faith-denying ecumenism practised by John Paul II, of which it is fitting to recall a few examples:

“It is with great joy that I send you my greetings, to you Muslims, our brothers in the faith of the one God” [Paris, 30 May 1981]

Statement to Hassan II, “Commander of the Faithful”: “We have the same God” [Casablanca, 19 August 1985]

“Today, I come to you, the spiritual heirs of Martin Luther; I come as a pilgrim” [Mainz, 17 November 1980]

Active attendance and preaching at a Lutheran service [Rome, 11 December 1983]

Reception of a delegation from B’nai B’rith (a branch of the anti-Catholic Freemasonry reserved exclusively to Jews), referring to it as a “meeting between brothers” [Rome, 17 April 1984]

Representation at the laying of the foundation stone of a mosque [Rome, 11 December 1984]

Participation in animist rites in the “sacred forest” [Lomé, Togo, 8 August 1985]

Reception of the “tilak sign” from a Hindu priestess [India, 2 February 1986]

Visit to the synagogue of Rome, with active participation in the service [14 April 1986]

Organisation of the Assisi gathering [27 October 1986].

The reality is that, in fact, those who wish to preserve the Catholic faith, to confess it in its entirety, and to produce its fruits, can do so only in opposition to the authority—or at the very least, apart from it.

The reality is that the authors or abettors of heresy and immorality live undisturbed within the conciliar structures, and that the furrowed brows provoked by a few noisy agitators in no way amount to a defence or promotion of the Catholic faith.

The reality is that the understanding of the faith is being destroyed by the invasion of personalism, which is the underlying philosophy implemented by the texts of Vatican II. Personalism, which has long since poisoned Catholic thought, is the philosophy of the rights of man, of openness to the world, of religious liberty, and of ecumenism—the philosophy that has led the Christian people to think and reason outside the light of the Catholic faith—and which, in turn, undermines that very faith.

This situation is incompatible with the existence of pontifical authority in Paul VI and John Paul II, because of the promise of assistance that Jesus Christ made to the Apostles and to their successors. This is what the Cassiciacum thesis sets forth and demonstrates—whose foundation, as one can see, is far broader than the single case of religious liberty.

To be sure, that case constitutes an extreme example, in which it is easy to show the radical incompatibility between the conduct of Paul VI and John Paul II and the possession of pontifical authority. But the Cassiciacum thesis was developed and refined by Father Guérard des Lauriers without relying on the case of religious liberty, and those who have presented, explained, defended, or illustrated it have never so reduced it, even if they have emphasised this particular point, which allows the situation of the faithful amid the Church’s crisis to be observed, as it were, “in vitro”.

Such are the initial reflections that come to mind on reading this letter in which Father de Blignières sets out the reasons for a volte-face; it was fitting to recall the ecclesial reality, and thus to show the illegitimacy of the inference drawn from, on the one hand, the absence of contradiction concerning religious liberty (whatever may be the case there, which Abbé Lucien will examine); and, on the other hand, the present existence of Authority at the head of the Church

And here is the epilogue of Monsieur l’Abbé Lucien.

‘Epilogue’

In a study intended to enlighten the faithful who have been troubled and scandalised by the volte-face at “Chémeré”, we could not undertake a detailed analysis of all the errors and false perspectives contained in the pamphlet by Brother Dominique-Marie de Saint-Laumer.

We believe we have shown sufficiently, on the two essential points, that his argumentation is without force. Let the reader judge.

But above all, let the Catholic faithful not forget the reality that lies plain before their eyes.

The defection of those who occupy the pontifical See since Vatican II is, first and foremost, a fact—continually manifested by the multiplication of acts and omissions contrary to the supernatural good of the Church, and by the complicit and widespread inertia in the face of the evident destruction taking place within the Church.

We must all ask for the grace to resist the Enemy, “strong in faith”, and to “persevere to the end”, not forgetting to pray to the Lord for the return of those who, not long ago, were fighting “the good fight of faith” but have now grown slack, that they may “repent and return to their first works.” Ut in omnibus honorificetur Deus [That in all things God may be glorified].

2. Abbé Lucien’s New Distinction

We must now respond to the first question:

By presenting [A] the distinction which forms the core of Abbé Lucien’s argumentation

By examining [B] the actual teaching of Vatican II

By recalling [C] the meaning and scope of the condemnations issued by Gregory XVI and Pius IX

By offering [D] some confirmations of what we are affirming.

[A] The Distinction—‘What has gone unnoticed’

Here is how Abbé Lucien proposes to resolve the contradiction between the declaration Dignitatis Humanæ of Vatican II and the condemnations issued by Popes Gregory XVI and Pius IX:

An essential difference between the right affirmed by Dignitatis Humanae and that condemned by Gregory XVI and Pius IX has been neglected.

Dignitatis Humanae affirms the natural right to the [external] liberty to act, in religious matters, according to one's conscience;

The two popes mentioned above deny the existence of a natural right to the external liberty to act, in religious matters, as one wishes.

(These two points may easily be verified by referring to the central sentence of Dignitatis Humanæ for the first, and to the first two chapters of my book on religious liberty for the second. See also below, sections 5 and 6.)

Indeed, it is quite possible, and alas very common, for a man to act as he wishes, though not according to his conscience. In fact, one who sins often acts against his conscience, whereas in other cases he acts according to his culpably erroneous conscience. It can even happen that man, hardened to the point of indifference towards good and evil, acts absent any judgment of conscience.

Moreover, the judgment of conscience in every man is exercised by practical reason, which first apprehends the general principles of the moral order. […] To be sure, knowledge of the general principles of morality and religion vary from one person to the next, according to the circumstances of social background, upbringing, and other more individual factors. But these diverse circumstances, which shape one’s access to the knowledge of general and universal principles, are of themselves observable from the outside.

Therefore, at least in part and in certain cases, it is possible to form a prudential judgment from the outside (supposing one has a legitimate reason to do so) regarding whether someone is acting according to his conscience or not. […]

Hence the right to act as one wishes not only is formally different from the right to act according to one's conscience, but in fact grants far more—at least under some societal circumstances—in terms of exemption from constraint.

There is, then, no contradiction between the condemnation of the former and the assertion of the latter.6

[B] The Teaching of Vatican II

Let us take up again the second paragraph of Dignitatis Humanæ, in which religious liberty is defined as Vatican II understands it:

This Vatican Council declares that a human person has a right to religious liberty. This type of liberty consists in the fact that, within necessary limits, all men need to be immune from coercion, whether deriving from individuals, social groups, or any human authority, in any matter of religion, in such a way that no one is either forced to act against his conscience, or impeded from acting in accordance with his conscience, regardless of whether he is acting in private or in public, alone or in association with others.

Abbé Lucien emphasises that only this right, as defined in the passage, is presented as the direct object of conciliar teaching and as founded on Revelation—and that therefore it alone is decisive.

This is true, on the condition that one specifies that a document of such importance must be read as a coherent whole (which it is); and that, in particular, the developments and consequences which are drawn from this initial affirmation will allow us both to clarify its meaning, and to determine the significance of the expression “according to his conscience”—which is the point in question here. This is all the more necessary because in paragraph 9 of the declaration, after these consequences have been set forth, it is reaffirmed that this doctrine has its roots in Revelation.

Now, the entire document shows that Vatican II intends not to make the right to religious liberty depend upon any subjective disposition—on whether one follows one’s conscience or not, whether one’s conscience is in error or not, whether the error of conscience is morally imputable or not.

This is what is affirmed at the end of that same second paragraph of the conciliar declaration:

The right to religious liberty, therefore, is not based on any subjective disposition of a person, but rather in the very nature of a person. That is why the right to this immunity remains even in those who do not meet their obligation to seek the truth and embrace it […]

Here is an authoritative commentary on this clarification, since it comes from Cardinal Bea, then president of the Secretariat for the Unity of Christians, who was responsible for the drafting of Dignitatis Humanæ:

“In other words, even the right of one who errs in bad faith remains entirely intact, provided that public order is respected—a condition that applies to the exercise of any right, as will be seen further on. And the conciliar document gives this peremptory reason: this right ‘is not founded […] on a subjective disposition of the person but on his nature’; it therefore cannot be lost on account of certain subjective conditions which do not, and cannot, changer the nature of man.”7

Even more authoritative is the interpretation given by John Paul II in an address to the fifth international colloquium on legal studies:

“This right is a human right, and therefore universal, because it does not arise from the upright conduct of individuals or from their correct conscience, but from the persons themselves—that is, from their inmost being which, in its constitutive components, is essentially identical in all persons. It is a right that exists in every person, and that always exists, even in the case where it is not exercised or is violated by the very subjects in whom it is innate.”8

It must therefore be held that the expression “according to his conscience,” which appears in the affirmation of the right to religious liberty, bears the meaning commonly given to it in the contemporary world: “according to one’s own intimate and personal decision, for which one is not accountable to men,” whatever the moral character of that decision may be. It is in this sense that the first paragraph of the declaration is to be understood:

“Men in this age are becoming daily more aware of the dignity of the human person. The number of those is growing who insist that men, in their actions, should enjoy and make use of their own counsel (proprio suo consilio) and responsible liberty, not forced by coercive means, but led in conscience by the recognition of a duty.”

This equivalence between “according to his conscience” and “according to his own will” is found throughout the document, which is in fact unintelligible unless this is admitted. Indeed, Dignitatis Humanæ declares the right to religious liberty for groups and communities—who, as such, have no conscience—just as much as for individuals. This is made explicit in the title and developed in paragraphs 4 and 5 of the conciliar document.

But it is above all the sixth paragraph that makes it impossible to understand “according to his conscience” in the classical, restricted sense. This paragraph in fact affirms the (civil) liberty to apostasize:

“Whence it follows that a public authority commits an execrable crime, if by force, by fear, or by any other means, it imposes upon the citizens the profession or rejection of any religion, or if it impedes the citizens from joining or leaving any religious community.”

Now, according to the most certain Catholic theology, it is impossible for a Catholic to leave the holy Church “according to his conscience”; thus teaches the First Vatican Council:

“Consequently, the situation of those, who by the heavenly gift of faith have embraced the catholic truth, is by no means the same as that of those who, led by human opinions, follow a false religion; for those who have accepted the faith under the guidance of the church can never have any just cause for changing this faith or for calling it into question.”9

This same paragraph 6 of [Dignitatis Humanae] stands in opposition to the Church’s centuries-old practice of requiring social discrimination on a purely religious basis—namely, the exemption of clerics from military service and from civil courts:

“Finally, civil authority needs to insure that the equality of citizens before the law, which is a component of the common good of society, is never violated, either openly or in secret, because of considerations of religion, nor that there be any discrimination among citizens.”

Abbé Lucien himself reveals that he misreads the conciliar definition of religious liberty when he asserts:

“Properly understood, the affirmation of Dignitatis Humanæ does not essentially call into question the Church’s practice in Christendom.”

Yet this practice [of the Church]—which consisted in opposing the religious liberty of non-Catholics—is explicitly rejected by paragraph 6 of the conciliar declaration:

“If, in response to the particular circumstances of a people, special civil recognition is accorded, in the legal structure of the body politic, to one religious community, it is necessary that, at the same time, the right to liberty in matters of religion, of all citizens and all religious communities, be recognized and observed.”

We may therefore conclude that the affirmation of Vatican II is not “correctly understood” by Abbé Lucien. The expression “according to his conscience” is not a restriction upon religious liberty—which is for “all citizens and all religious communities” (§ 6.2). The entire unfolding of the doctrine on religious liberty disregards the clause “according to his conscience” and even contradicts the traditional meaning of that expression. After this, Vatican II declares (§ 9):

“This teaching about liberty has roots in divine Revelation—all the more reason, then, why Christians should keenly defend it.”

[C] The Condemnations of Gregory XVI and Pius IX

Abbé Lucien asserts that the popes of the nineteenth century condemned the right to act as one pleases. This expression is not found in their writings, and so Abbé Lucien appeals to the lexicographical inquiry in his work on religious liberty (pages 27 to 32) to argue that the phrase “liberty of conscience” had that meaning in their time; he sees in this at least a “strong presumption.”

Yet if one examines it point by point, one finds that out of 14 references, 5 specify “according to what one believes to be true” or something equivalent, 2 specify “as one pleases,” and 7 specify nothing. This shows that the expression shifts easily from one sense to the other (as does Vatican II in its use of “religious liberty”); and in reality, it abstracts from the question of whether or not one is following one’s conscience.

This seems to us perfectly natural, since the legislative and juridical order of society cannot be founded upon the state of a person’s conscience, nor conditioned by it; public law refers solely to the common and objective good.

There is therefore indeed an identity between the “liberty of conscience” condemned by the Church and the “religious liberty” affirmed by Vatican II. Nowhere, in fact, do Gregory XVI or Pius IX exclude from their condemnations the right of one who follows his conscience, or anything similar; their condemnations have a general scope, just as does the affirmation of Dignitatis Humanæ. In both cases, it is religious liberty, plain and simple.

[D] Confirmations

Numerous passages in Abbé Lucien’s book on religious liberty retain their full force in demonstrating the perversity of religious liberty, even if one admits the distinction he now proposes:

“According to traditional doctrine, religious truth—and concretely, the shared possession of this truth and the common practice of the true religion—is a major element of the common good. And this is why, in itself, the propagation of religious error is contrary to the common good: hence the impossibility of a natural right, a right of the person, to liberty in religious matters.” (page 283)

“Gregory XVI does not merely reject an unlimited liberty of opinions, without further clarification. He indicates, in the most explicit terms, how to determine the proper limit: what is disastrous is the liberty of error; a restraint is needed—authority with its coercive power—to keep men in the path of truth.” (page 38)

Since this concerns the common good and the legislative order, subjective dispositions are irrelevant. If religious error is preached, the preacher’s good faith will not lessen the ravages caused in souls and in society (perhaps even the contrary). The common good will nonetheless be harmed—and it is that which the law is meant to uphold.

Conclusion

The distinction proposed by Abbé Lucien is, on the one hand, absent from the condemnations issued by the Church, and on the other, purely verbal. It is real in itself, of course, but it cannot be so either in the affirmations of Vatican II, or in relation to the juridical and legislative order—for that is indeed what is in question—which cannot be founded upon a state of conscience or conditioned by it, nor in relation to the common good which the law must promote.

The contradiction between Vatican II and Catholic doctrine thus remains entire.

Having answered “no” to both questions required by the examination of Abbé Lucien’s letter, we therefore twice over refuse to follow him. This is not without a particular sorrow at his defection; and, since in the epilogue we reproduced above he exhorted readers to…

“… pray to the Lord for the return of those who not long ago were waging the ‘good fight of the faith’, but who have now slackened, that they might ‘repent and return to their first works…’”

… we shall apply the law of retaliation and pray for him with fervour and perseverance.

Abbé Hervé Belmont

P.S.

One will find confirmation of the refutation of Abbé Lucien in the article of a staunch partisan of religious liberty—though one who retains a certain moderation—Father John Courtney Murray S.J:

“In the declaration’s formula ‘juxta conscientiam’ or ‘contra conscientiam’ [according to conscience / against conscience], the meaning of the term conscience coincides with the sense of the initial formula: according to one’s own free and personal judgment. The meaning is therefore not technical, but broad; it is sufficiently sanctioned by popular usage. […]

“The question of the truth or error of conscience has no connection with the juridico-social problem of religious liberty. This liberty is exercised within civil society. Now, there exists no authority in civil society—not even the power of the State—that is capable of passing judgment on the truth or error of men’s consciences.” Page 4710

HELP KEEP THE WM REVIEW ONLINE WITH WM+!

As we expand The WM Review we would like to keep providing free articles for everyone.

Our work takes a lot of time and effort to produce. If you have benefitted from it please do consider supporting us financially.

A subscription gets you access to our exclusive WM+ material, and helps ensure that we can keep writing and sharing free material for all.

(We make our WM+ material freely available to clergy, priests and seminarians upon request. Please subscribe and reply to the email if this applies to you.)

Subscribe to WM+ now to make sure you always receive our material. Thank you!

Read Next:

Follow on Twitter, YouTube and Telegram:

Abbé Belmont rejects the legitimacy of espicopal consecrations conferred without papal mandate, even in our current situation.

Editor’s Note: This phrase “as a whole” is evidently rhetorical. It is very clear what Fr Belmont means by it, and that he does not mean the words in their literal sense. Nonetheless, the phrase is extremely unfortunate.

Editor’s Note: “Immanent Apostasy”—This appears to be a reference to Jacques Maritain’s term apostasie immanente (“immanent apostasy”). Coined in 1965, it seems to describe what he saw as a novel form of apostasy in which the substance of the Christian faith is rejected, yet the name and appearance of Christianity are deliberately retained. It denotes a self-contradictory falling away: not open renunciation, but the internal abandonment of divine and Catholic faith under the guise of fidelity.

Apostasy is typically defined as the complete turning away from the faith, while heresy is defined as the denial of individual truths while retaining the Christian name. While Maritain’s concept may appear to be contradictory, it does convey something of the reality of our day—apostasy masked as heresy, which is in turn masked as orthodoxy by preserving outward forms, while dissolving the content they once signified.

See more from Jean Madiran: http://agoramag.free.fr/102002JMadiran2.html

Abbé Bernard Lucien, Religious Liberty, Continuity or Contradiction? pp 6-9. Trans. John Pepino, Arouca Press, Waterloo, ON, 2025.

Revisia del clero italiano, May 1966; La Documentation Catholique, 3 July 1966, col. 1186

10 March 1989, La Documentation Catholique, no. 1974, p. 511

20 April 1870, Denzinger no. 1794

Nouvelle Revue Théologique, 1966, no. 1, pp. 41–67

One thing that always gets me about this debate is those who try to defend Dignitatis Humanae act like it lives in a vacuum. They always say “you *can* interpret it an an orthodox way” but they fail to truly acknowledge how has the modernist hierarchy (you know, those actually charged with interpreting and implementing the documents) interpreted it. From episodes such as Assisi 1986, Ratzinger’s giving communion to the Calvinist “Brother Roger” of Taize, it’s clear that the “orthodox interpretation” of DH is neither the one of the hierarchy nor the intended one of the original writers

Thank you for an excellent article. I believe the civil acceptance of abortion, homosexuality, etc. are a direct consequence of DH, let alone their acceptance within the Church or at a minimum not a few of Its members both lay and clerical. For there is no definitive argument against these practices except the religious one in the personal and civil spheres. The Nancy Pelosi argument exists, "I may be personally opposed to X but I can not 'coerce' someone else by supporting a law against it", because of this freedom of conscience and inherent unremitting human dignity never to be treaded upon. Under its terms the Church would have dissolved the Holy Roman Empire itself, just as it did all Catholic states. Indeed we see the criminalization of members of the Church for even teaching against these practices, a hate crime.

DH dovetails with the New Theology, a redefinition or even denial of sin, hell, and Christ Himself, a sense of universal salvation, as well as the liturgical reform with the deemphasis in its readings on the four last things and God's retribution for sin in the natural world. It is all of a freemasonic piece, John Courtaney Murray's undoubted inspiration being the U.S.A., materially flourishing and spiritually dying. As the author states one must look at DH in this entire context and its miserable fruit and acknowledge its heterodoxy.