Occult and esoteric ‘trad world': Silence breaks at last?

Links between certain ‘traditional’ Catholic figures and occult/esoteric ideology are finally being taken seriously.

Links between certain ‘traditional’ Catholic figures and occult/esoteric ideology are finally being taken seriously.

(WM Round-Up) – Michael Warren Davis’ blunt review of Sebastian Morello’s Mysticism, Magic and Monasteries (which we briefly covered here) has prompted scrutiny over its author and the network of Catholic figures with which he is associated.

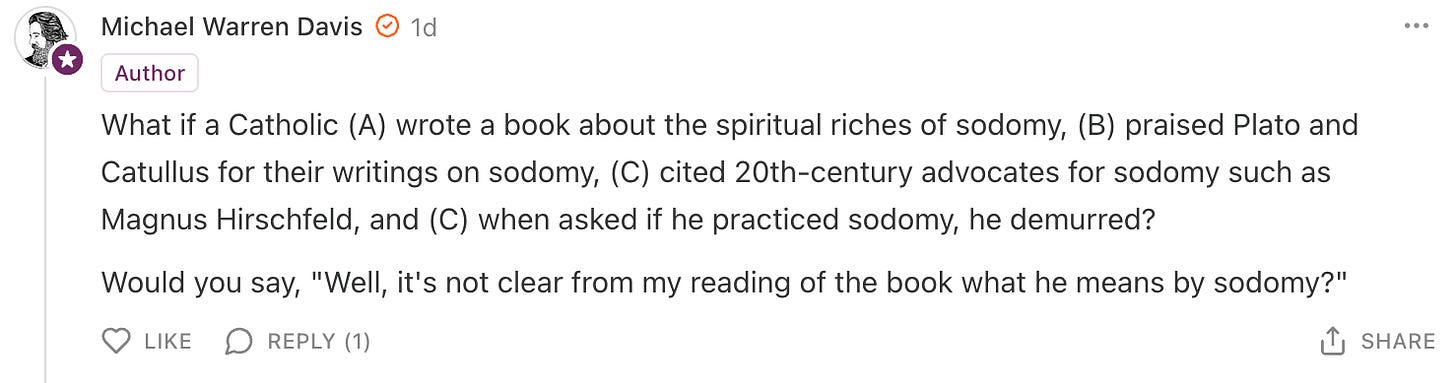

Davis has since doubled down on his critique. When challenged on his understanding of Morello’s intentions in referring to “sacred magic,” Davis wrote:

What if a Catholic (A) wrote a book about the spiritual riches of sodomy, (B) praised Plato and Catullus for their writings on sodomy, (C) cited 20th-century advocates for sodomy such as Magnus Hirschfeld, and (C) when asked if he practiced sodomy, he demurred?

Would you say, "Well, it's not clear from my reading of the book what he means by sodomy?"

Developing this analogy, he expressed his belief that Morello actually practices some form of magic himself.

I'm not trying to be harsh but I think Ms. Angelou was right when she said, "When someone tells you who they are, believe them."

Morello wrote a book praising magic. He used specific terms like theurgy, egrigore, familiar, etc. He cites at great length authors who absolutely performed rituals that the Church would consider diabolical. Others in his circle, who endorse his book, are known to participate in such rituals as well. And when asked if he performs such rituals, Morello refuses to answer.

There can be no "benefit of the doubt" where there's no doubt.

And:

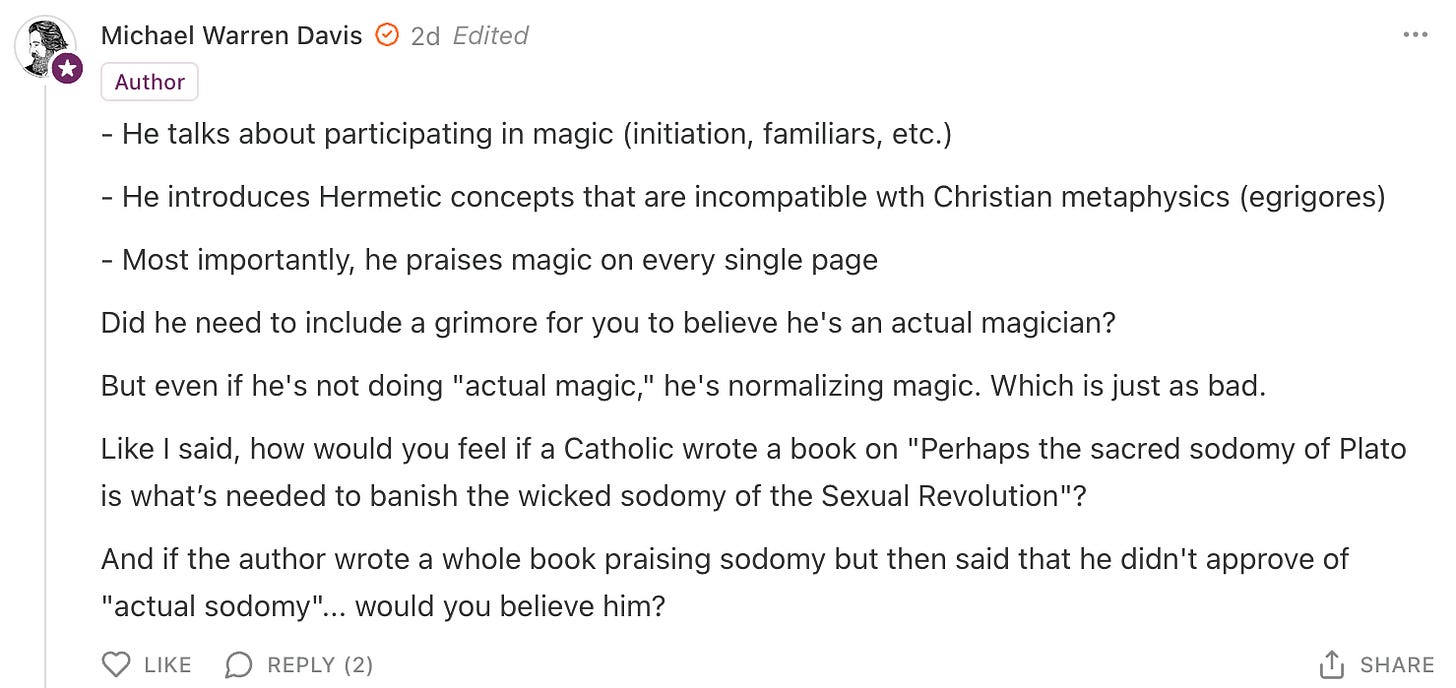

- He talks about participating in magic (initiation, familiars, etc.)

- He introduces Hermetic concepts that are incompatible wth Christian metaphysics (egrigores)

- Most importantly, he praises magic on every single page

Did he need to include a grimore for you to believe he's an actual magician?

But even if he's not doing "actual magic," he's normalizing magic. Which is just as bad.

Hermeticism

What is the “hermeticism” to which Davis refers? How can it be defined?

This article is a survey of the controversy, rather than analysis of the ideas. But in a sense, the definition of hermeticism here is irrelevant, because Morello states that the word means different things depending on who is using it.

He personally “defines” what he means by it in the final part of his series Can Hermetic Magic Rescue the Church—Chapter V of the book—prefacing his definition with significant caveats:

Typically, Christians are uneasy at any mention of Hermeticism or esotericism. This is understandable, for such terms have come to mean anything that is not modern mainstream Christian spirituality. In this way, ‘Hermeticism’ is rather like the term ‘alternative medicine,’ which doesn’t tell you what it is but what it’s not, namely not modern mainstream medicine. Thus, ‘alternative medicine’ can mean anything from eating cooked elderberries to support one’s immune system, to Reiki. Likewise, depending on what one is reading, ‘Hermetic’ or ‘esoteric’ could mean anything from “concentration without effort” (a practice similar to those recommended in Jean Pierre de Caussade’s Abandonment to Divine Providence) to the sex magic of Aleister Crowley.

What I mean by ‘Hermetic’ is a set of practices and disciplines of mind, will, and imagination, that habituate in the practitioner a vision of the world that acknowledges it as God’s Icon. This, I claim, was the shared vision of pre-modernity, and more generally the shared metaphysical vernacular of all broadly religious ontologies. And it is the vision we likely have to recover if we’re to break the spell that established modern man, who is a disintegrated, centaurial creature due to his acceptance of the rationalist paradigm and his retreat from grace.

The goal—seeing the world as “God’s Icon”—might sound worthy. But what are the “practices and disciplines of mind, will, and imagination” that he has in mind? Are they the ones he talks about in The Gnostalgia Podcast?

Are they sanctioned or enjoined by the Church? Are they compatible with the Catholic religion? If they are not yet “baptised,” is it actually possible for them to be?

Do they achieve what they are supposed to achieve, or are they manifestations of superstition, or worse?

Is it really necessary to look outside the Church for them? What are the implications of this for the Church’s claims?

If seeing the world as '“God's Icon” is “the shared vision of pre-modernity, and more generally the shared metaphysical vernacular of all broadly religious ontologies,” why are we even discussing a possible need for Catholics to turn to Hermeticism, of all systems, in order to gain a greater sense of it? And how does Morello’s suggestion that the Church “offer a chair at its table to Hermes Trismegistus” differ essentially from previous attempts to rehabilitate this mythical figure—such as that of the sixteenth-century Neoplatonist philosopher Francesco Patrizi, whose efforts to do so saw his work condemned by the Inquisition?1

These are important questions. But in the meantime, we could also turn to Fr Edward Cahill SJ gives a brief summary in his 1947 Freemasonry and the Anti-Christian Movement. Noting that “the whole system of occultism” which “is sometimes called Hermeticism” is “so elusive and difficult to define,” he writes:

Hermeticism is commonly taken to include Theosophism, Christian Scientism, Neo-Platonism, Philonic Judaism and Jewish and pagan Cabalism. It is in a large part a revival of the heresies of the Gnostics, Manichaeans, Albigenses, Waldenses, etc., and aims at providing the modem European race with some acceptable substitute for Christianity.2

In the same work, Cahill writes:

We have already referred to Rationalism and Hermeticism (including Theosophy, Christian Scientism, Spiritism, etc.) as characteristic of the Masonic religion and philosophy. These, which are put forward as a substitute for real religion, are fast becoming more and more widespread in England and throughout the English-speaking world. They are the most powerful dissolvents of whatever elements of true Christianity still survive among the Protestant populations.

Infiltrations even into Catholicism are being attempted. This element is perhaps the most deadly and dangerous aspect of the whole Masonic movement; for it cuts deeper than anything else into Christian life, whose very foundation it attacks.3

If the word “hermetic” can mean almost anything, as Morello claims, why use it at all, given these odious connotations?

About Morello’s magic book

The book on magic itself was published by Os Justi Press, a traditionalist imprint. Most (or possibly all) of the chapters were previously published in an earlier form at The European Conservative or elsewhere.4

It is influenced by a strange set of sources, including the controversial Valentin Tomberg, author of Meditations on the Tarot: A Journey into Christian Hermeticism and other works. Tomberg is also cited positively by others in the mainstream “traditionalist movement,” including the UK Latin Mass Society chairman Dr Joseph Shaw.5 Meditations on the Tarot is presented as a means of evangelising those involved with the esoteric and occult, but Tomberg expresses a number of strange ideas within—including his belief in universal salvation,6 as well as reincarnation,7 expressed in terms almost identical to the Kabbalistic explanation of the well-known Chabad-Lubavitch Rabbi Simon Jacobson.8

It also contains a series of dismissive comments about St Ignatius, his Society of Jesus and his Spiritual Exercises, all of whom he blames for the spread of “rationalism.” We will be critiquing his irreverent approach in due course.

Despite this, Morello's book features endorsements from mainstream traditionalist favourites Shaw and Charles Coulombe, and received rave reviews from mainstream conservative and “traditional” Catholic outlets at the time of publication.

The Catholic Herald called the magic book “a brilliant excoriation” of the modern world, and praised its references to “Tomberg’s Meditations on Hermeticism (also owned by Pope John Paul II)” as well as to “psychoactive fungi and the Perennialists.”

New Liturgical Movement described it as “full of rich reflections on the thought and culture of antiquity” and provided a series of extended quotations. Tim Flanders of The Meaning of Catholic was also very positive about it in a February 2025 video.

These reviews raise the question of how and why these mainstream conservative and “traditionalist” figures could be praising such a work—and with evident knowledge of what it contains.

Silence broken after four years?

However, such links between this world and “the occult” are not a new discovery. In 2021, the author Alistair McFadden published an eight-part monograph which dealt with a broad network of “traditional Catholics” engaged in promoting occult, esoteric, perennialist and hermetic ideas.

Initial support for McFadden was mostly limited to sedevacantist circles. About a month after publication, True Restoration and Novus Ordo Watch published a summary, which prompted the controversy that ensued.

Critics seized on McFadden’s mention of Charles Coulombe and his annual tarot card readings at the Theosohical Society’s Besant Lodge in Los Angeles, with the Gnostic “Bishop” Stephan/Stefan Hoeller. They proceeded to defend Coulombe in a sustained online pile-on against McFadden.

Those on Coulombe’s side of this backlash did not acquit themselves well. The affair very clearly manifested tactics similar to those described by Pope St Pius X in his encyclical Pascendi Dominici Gregis:

[T]he Modernists vent all their bitterness and hatred on Catholics who zealously fight the battles of the Church. There is no species of insult which they do not heap upon them, but their usual course is to charge them with ignorance or obstinacy.

When an adversary rises up against them with an erudition and force that renders them redoubtable, they seek to make a conspiracy of silence around him to nullify the effects of his attack.

This policy towards Catholics is the more invidious in that they belaud with admiration which knows no bounds the writers who range themselves on their side, hailing their works, exuding novelty in every page, with a chorus of applause. For them the scholarship of a writer is in direct proportion to the recklessness of his attacks on antiquity, and of his efforts to undermine tradition and the ecclesiastical magisterium.

When one of their number falls under the condemnations of the Church the rest of them, to the disgust of good Catholics, gather round him, loudly and publicly applaud him, and hold him up in veneration as almost a martyr for truth.

Even if the network of personalities involved may not be properly described as modernists, the similarities are striking, not least because those who form this network are indeed almost all proponents of an ideology which seeks to “rethink the papacy”—namely, “to diminish and weaken the authority of the ecclesiastical magisterium,” which it achieves in part “by freely repeating the calumnies of its adversaries” namely Old Catholics, Orthodox, and so on. This, along with current controversy, are good reminders that being “attached” to traditional forms of liturgy is radically insufficient without the traditional faith and doctrine of the Church—including on the papacy.

As a result of the 2021 pile-on and the exaggerated focus on defending Coulombe, the concerns raised about the network under discussion—e.g., Angelico Press, The Association of Hebrew Catholics, Joseph Shaw, Stratford Caldecott, Robert Spaemann, Wolfgang Smith, and Malachi Martin—were pushed aside at the time.

After the affair died down, McFadden’s work was indeed buried under “a conspiracy of silence”—treated dismissively, but never refuted.

It was notable at the time that the figures implicated in McFadden’s study were nearly all of a “mainstream” bent—namely, conservatives, or mainstream “traditionalists,” in more or less good standing with the conciliar authorities.

The same applied to those who defended these figures. On the other hand, the interest taken by sedevacantists was and is used as a pretext to discredit McFadden’s study, rather than address it. This has been compounded as, some time later—after a series of discussions with an editor of this publication and others of like mind—McFadden drew the same conclusion about Francis and the post-conciliar claimants.

The precise nature of the “Influence of the Occult on Traditional Catholic Discourse,” to which McFadden refers, is very interesting and important, but outside of the scope of this piece. Readers are encouraged to read his piece, or the summary mentioned.

McFadden vindicated

Now, four years later, others have noticed what has been going on amidst this network. They are expressing their own concerns, and referring to the same ideas that McFadden flagged in 2021.

Thomas V. Mirus wrote in response to Davis’ critique:

Morello’s framing the Church’s sacred rites as a form of magical theurgy (the method by which Neoplatonists tried to summon demons), prayer as a set of magic words, sacramentals as talismans, and his placing the supernatural action of God on the same plane with the purportedly “opposing forces” of white and black magic, must be rejected as blasphemous. His argument that Christians already believed in magic all along is a transparent attempt to smuggle foreign elements into our faith.

He adds, writing of McFadden’s study:

[A]t the time of its publication in 2021 I followed up on much of the author’s research and found it generally accurate. It is still essential reading for those who wish to be aware of the influence of occultism and false mysticism within a certain scene of traditionalist or conservative Catholic intellectuals.

It was met with extreme defensiveness by many prominent traditionalist figures at the time of its publication.

Responding to Mirus’ article on facebook, Thomistic philosopher Matthew K. Minerd wrote:

While admitting that one must be very careful about the details of these matters, I think Thomas Mirus is not wrong to sense that there are dangers in the water. […] In short, I think the sorts of dangers Thomas identifies are very real ones in our present moment.

Chris Jackson, now publishing at Hiraeth in Exile, has also begun a series on “the occult revival in traditional Catholicism,” returning to the same themes of McFadden’s study and thanking him “for inspiring this series.”

As someone who became acquainted with McFadden during the pile-on, I am glad to see him being vindicated, and others taking this strange phenomenon seriously.

But why did it take four years, and a review by an ex-Catholic for people to start taking this seriously?

Davis himself has released a second part to his review, aimed at Eastern Orthodox readers, and which contains a number of tropes about the defects of Catholic scholasticism and philosophy. While it does not add much to the first part, he provides what he calls an “odd passage” from the book—originally published in The European Conservative as part of Morello’s trilogy ‘Can Hermetic Magic Rescue the Church?’

I declare that Christ alone can rescue His Church, but we have ousted Him in a diabolic effort to divorce Bride from Bridegroom. We have lost the primacy of the supernatural; however much the Lord may seek to rescue His Church from its current trajectory of self-destruction, He finds a Church whose members largely don’t believe they need rescuing. They are under a spell, and that spell must be broken. Perhaps the sacred magic of Hermes Trismegistus is what’s needed to banish the black magic of Enlightened man. (p.80)

Davis witheringly summarises this passage thus:

Only Christ can save His Church, but only Hermes can save Christ.

Morello’s other work

At present, Morello is the contributing editor and editorial board member of The European Conservative and a columnist for the UK Latin Mass Society’s magazine Mass of Ages.

At one point, he worked for a catechetical organisation in Southwark diocese. On YouTube, there are a number of videos of him delivering talks on Catholic doctrine and devotion in a very standard, non-esoteric way.9 However, even then he was engaged in these ideas—in the preface to the book, he writes:

Those who know me, know that I have long harboured esoteric interests. When I taught at a catechetical institute in London, I was always accompanied by my whippet Pico, named after the fifteenth-century Christian Hermeticist Giovanni Pico della Mirandola, a man whom St. Thomas More described as “a perfect philosopher and a perfect theologian.” The name which I affectionately bestowed upon my familiar [!] was partly to signal to the initiated that I too was a lover of the Secret Fire.”10

Notwithstanding the qualities which led to St Thomas More’s praise, Pico’s book of 900 propositions (even if not his person) was condemned by the Church.11

UPDATE: Following further research, we have established that attributing these words to St Thomas More is extremely misleading, if not false. For more, see here:

At some point in the last ten years or so, Morello became open about these interests, and has since explicitly positioned himself in this space. In a December 2024 podcast, joking with Coulombe about the effects of McFadden's study, Morello claimed he had “picked up the baton” from Coulombe.12

In his role as co-host of The Gnostalgia Podcast, he has interviewed guests such as Joseph Shaw13 (on “Liturgy as Sacred Magic”), Rod Dreher14 and Charles Coulombe,15 and discussed topics such as the merits and demerits of psychedelic mushrooms,16 ritually cursing ones enemies,17 “cosmic Mariology” and the “divine feminine,”18 and invoking the “gods” and fairies that protect England’s woodland and countryside.19

In one podcast, Morello relates how he was told by Roger Buck that Tomberg, having become a “daemon” (“in the hellenistic sense”) had been leading and guiding Morello “in his divinised condition in the celestial spheres,” drawing him in a “Tombergian” direction.

“Tomberg,” Buck apparently said, “has been sitting with you in your study the whole time, in a very literal sense. He has been one of the gods walking among you and guiding you.” Morello summarised this by saying, “So, that was cool.”

Morello admitted that some of their “more normie listeners might get the heeby-jeebies” from hearing about these conversations with Buck.20

Morello’s defenders

Morello himself has not yet commented, but these reviews seem to have rattled those linked with him.

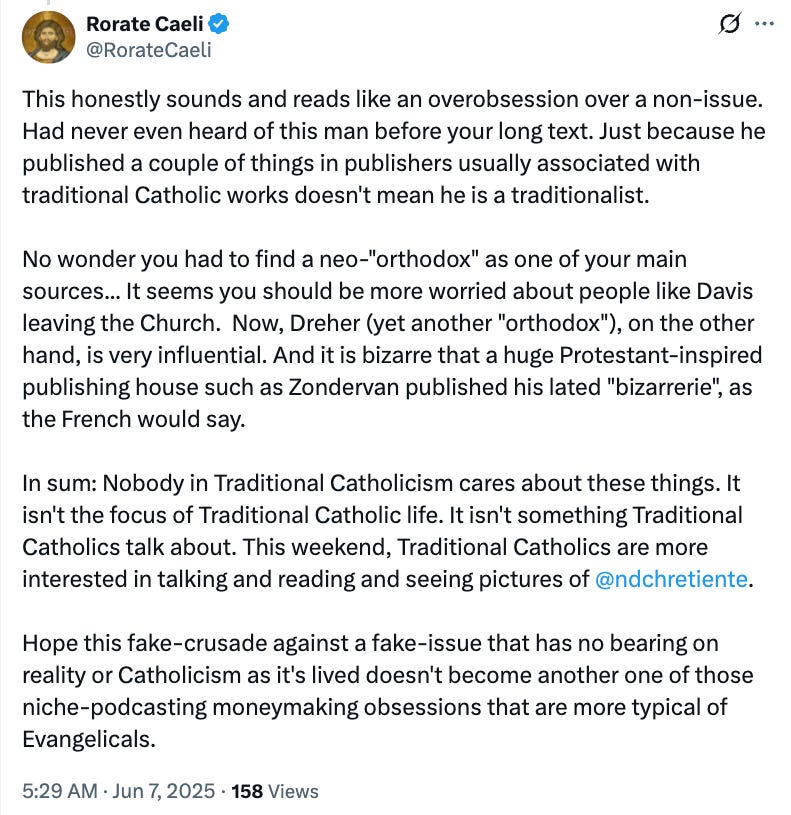

Rorate Caeli dismissed the issue, claiming that he had “never even heard of [Morello]” before Mirus's post, and disclaiming his “status” as a traditionalist—despite the lauding of his book by the network, and Morello’s name appearing on a dozen articles on his own website.

The idea that “nobody” cares or talks about these issues rings hollow in light of the previous furore in 2021, as well as the reviews of Morello’s book discussed above.

Shaw has also leapt to the defence of the man whose book he has promoted, and who has been closely associated with the Latin Mass Society. Unfortunately, Shaw focused on Dr Minerd’s references to Iain McGilchrist, without addressing the broader concerns:

Is it charitable to condemn by association a text one has only ‘flipped through’? Is is intellectually honest? Is it wise? As a matter of fact Sebastian Morello is very critical of McGilchrist. You need to get your friends and enemies list sorted out.

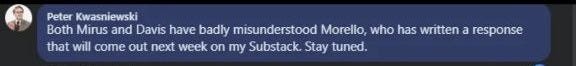

More significantly, Kwasniewski—who runs the Os Justi Press imprint and features Sebastian Morello as a writer on his website—has responded on facebook:

Both Mirus and Davis have badly misunderstood Morello, who has written a response that will come out next week on my Substack. Stay tuned.

Kwasniewski followed this with a longer post, calling Davis and Mirus’ critiques “calumnious attacks.”

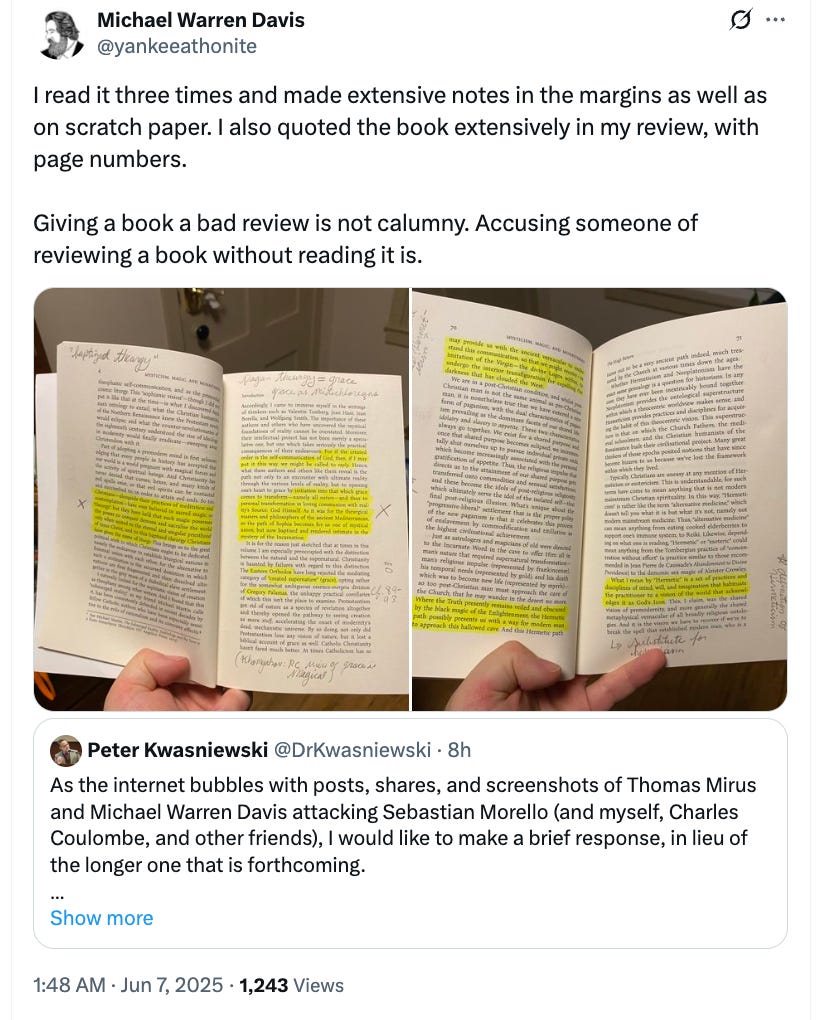

But are critical reviews “calumnious”? Surely not. Davis also says no, and is not backing down on his critique:

I read it three times and made extensive notes in the margins as well as on scratch paper. I also quoted the book extensively in my review, with page numbers.

Giving a book a bad review is not calumny. Accusing someone of reviewing a book without reading it is.

It also should be noted that, as almost all of the chapters have already been published in earlier form online, more people have probably “read the book” than realise it themselves—even if these chapters have been edited or expanded to some degree for publication.21

Many have also heard Morello speak for himself, whether in interviews and on his podcast. His ideas are hardly an unknown quantity.

In any case, responding to criticism with accusations about calumnious attacks simply again recalls the tactics mentioned by Pope St Pius X. Morello took a similar approach a few weeks ago, presenting himself as the “victim” of “online sedevacantists”:

It turns out that there's this whole wing of the internet run by online sedevacantists who are desperate to accuse people of being sort of witches or crypto-occultists or something.

And from various screenshots that my friends send me, to either amuse me or provoke me, it turns out that I'm their latest victim.22

But is one a “victim” for being the subject of critique? Surely not.

The caricature of sedevacantists uncharitably accusing others of being “crypto-occultists” runs rather hollow. After all, The Gnostalgia Podcast’s twitter account has responded to calls for dialogue over the current controversy by dismissing those “who have already closed themselves to the idea of magic”!

I’m not sure how much those who have already closed themselves to the idea of magic would benefit from the dialogue. It may end up just preaching to the choir whilst all being in agreement.

Perhaps a more serious historical response will need to be written following the sources through the ages with an emphasis on those who made distinctions between natural magic and black magic. Perhaps Kingsnorth has too much of a bee in his bonnet about Morello for the dialogue to be fruitful regardless.

However, as Michael Warren Davis said in his first review:

[I]magine if we showed Morello all the passages where Scripture and the Fathers condemn magic. I know exactly how he would respond. He’d give us a certain look—knowing, pitiful, a little bored—and say, “Of course, I’m not talking about that kind of magic.” But where does the Church ever differentiate between good and bad magic?

The same place where it distinguishes between good and bad pederasty, good and bad abortions, etc.

Conclusion: Honesty or misdirection?

Davis has also “gone on record” on Twitter with his prediction for Morello’s apologia.

Before Morello's response comes out, I want to go on record predicting that he will say anything other than "magic is evil."23

We will update readers when Morello’s “side of the story” is published by Dr Kwasniewski on Tradition & Sanity.

However, in 2021, McFadden’s substantive points became obscured by the misdirection which made everything about Coulombe—which was very convenient for the others implicated in his study. We will see whether the same tactic of misdirection is employed here.

It is true that this controversy has been prompted by a review of Morello's book, but the issue is much wider—pertaining to the ideas and tendencies themselves, and the network of personalities who are promoting the same interest in the occult.

Update:

Peter Kwasniewski has published Sebastian Morello’s reply to Michael Warren Davis (Yankee Athonite) and Thomas V. Mirus. As promised, here is Morello’s reply.

Morello’s reply was interesting in many ways. I shall not be responding to it for now. In the meantime, I appreciated Dr Minerd’s comment on Twitter and broadly agree with what he said.

With thanks to Alistair McFadden for his 2021 research, as well as for assistance with locating some of the sources used here.

HELP KEEP THE WM REVIEW ONLINE WITH WM+!

As we expand The WM Review we would like to keep providing free articles for everyone.

Our work takes a lot of time and effort to produce. If you have benefitted from it please do consider supporting us financially.

A subscription gets you access to our exclusive WM+ material, and helps ensure that we can keep writing and sharing free material for all.

(We make our WM+ material freely available to clergy, priests and seminarians upon request. Please subscribe and reply to the email if this applies to you.)

Subscribe to WM+ now to make sure you always receive our material. Thank you!

Read Next:

Observations on the Influence of the Occult in Traditional Catholic Discourse

Follow on Twitter, YouTube and Telegram:

In Patrizi, we have an expounder of a "new philosophy" strongly influenced by Hermetism and going back, behind the more recent attempts to purify Hermetism of magic, to the Ficinian atmosphere with its belief in prisca magia. This philosophy is anti-Aristotelian, in the sense that it claims to be more religious than Aristotle. Its author hopes that the Pope will use it in the Counter Reformation effort, as a means of reviving religion and converting the Protestants.

In 1592, Patrizi was called to Rome by Pope Clement VIII to teach the Platonic philosophy in the university. He must have gone to Rome full of hopes that this summons meant that he was to be allowed to teach and preach there the Hermetic Counter Reformation which he had outlined in his "New Universal Philosophy". But critical voices were raised against his ideas, he got into trouble with the Inquisition,” and consented to revise and retract whatever was thought heretical in his book. But the book was eventually condemned, and though Patrizi was not otherwise punished (he seems to have retained his chair until his death in 1597) he was, in effect, silenced, and his effort to put “Hermes Trismegistus, contemporary of Moses” back into the Church, as at Siena, did not receive official encouragement. His story illustrates the mental confusion of the late sixteenth century and how it was not easy, even for a most pious Catholic Platonist like Patrizi, to realise how he stood theologically (the position about magic was being drawn up by Del Rio when Patrizi was in Rome but was not yet published).

Frances Yates, Giordano Bruno and the Hermetic Tradition, 1964, p 184

Related:

A large number of the later Renaissance school were Christians only in name. If the great body of them were judged by the heathen figures and phraseology with which their works abound, they could hardly be acquitted of Pagan tendencies; but in case of many of them these excesses are to be attributed to pedantry rather than to defection from the faith. In case of others, however, although they were wary in their expressions lest they might forfeit their positions, Christian teaching seems to have lost its hold upon their minds and hearts... [T]he well-known exponent of Platonic philosophy Marsilio Ficino [and others]... were openly Pagan in their lives and writings. Had the men in authority in Italy been less depraved such teaching and example would have been suppressed with firmness; or had the vast body of the people been less sound in their attachment to Christianity, Neo-Paganism would have arisen triumphant from the religious chaos."

Fr James McCaffrey, A History of the Catholic Church from the Renaissance to the French Revolution, Vol. I, p 9-10 1915. McCaffrey was the Professor of Ecclesiastical History at St Patrick's College, Maynooth.

At the side of traditional Thomism, and often in conflict with it, there developed... the semi-pagan Neoplatonism of Marsilio Ficino... Ficino's doctrine, so brilliantly set forth in his Theologia Platonica, was nothing else but Plato's doctrine as interpreted by Plotinus... Would it be possible to consider the teachings of Christ and of the Church as a vast syncretism wherein all the religions of antiquity would providentially meet? Marsilio Ficino seems to maintain this in his treatise De Religione Christiana, wherein, without abandoning the dogma and the traditional proofs of the Church, he seems too much inclined to dissolve Christianity into a sort of enlarged paganism.

Fr Fernand Mourret, A History of the Catholic Church, Vol. 5 p 285. Mourret’s work was quoted and praised as "masterful" by Charles Coulombe in his foreword to Morello's book (p xii).

‘Ficinian’ rituals are described as follows:

Francesco da Diacetto, a close disciple of Ficino, describes a Ficinian ritual in which the magician seeks to direct a powerful channel of solar energies. Robed in a mantle of solar color, such as gold, the subject should burn incense made from solar plants before an altar adorned with an image of the sun enthroned and crowned, wearing a saffron cloak. Anointed with unguents made from solar materials, he sings an Orphic hymn to the sun.

This concentration of solar properties and influences in the lower, mundane world serves as a kind of lens to focus the solar influences from the higher, astral world. The solar aspect of the various creatures, images, and artifacts attracts the downpouring of solar energy from the Sun and concentrates it around the figure of the magician.

Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke, The Western Esoteric Traditions, 2008, p 41.

Reader beware. However, it does allow readers to see what is actually being discussed.

Foreword by Charles Coulombe

Preface

Acknowledgments

Introduction

The Loss of Sacred Places

The Fall of Monasticism and the Rise of Clerical Managerialism

Appendix I. A Correspondence with Peter Kwasniewski on Grace, Vocation, and the Modern Church

Appendix 2: A Response to Rod Dreher’s Living in Wonder.

The soul of Origen was also prostrated in the face of the victory over eternal hell and moved by the revelation contained in the words: “It is I”" spoken by Him who had just come out from eternal hell. This is why Origen himself knew with certain knowledge that there would be no “damned” at the end of the world and that the devil, also, would be saved.

And whoever meditates on the sweat of blood in Gethsemane and on the words “It is I” (or “I am he”), announcing the eternal victory over eternal hell, also will know with certain knowledge that eternal hell exists as a reality, but that it will be empty at the end of time. The sweat of blood in Gethsemane is the source of “Origenism”; here is the source of its inspiration.

Valentin Tomberg, Meditations on the Tarot, p 199 of this edition.

For the Hermeticist it is a fact which is either known through experience or ignored. Just as one does not make propaganda for or against the fact that we sleep at night and wake up anew each morning —for this is a matter of experience—so is the fact that we die and are born anew a matter of experience, i.e. either one has certainty about it or else one does not. But those who are certain should know that ignorance of reincarnation often has very profound and even sublime reasons associated with the vocation of the person in question. When, for example, a person has a vocation which demands a maximum of concentration in the present, he may renounce all spiritual memories of the past. Because the awakened memory is not always beneficial; it is often a burden. It is so, above all, when it is a matter of a vocation which demands an attitude entirely free of all prejudice, as is the case with the vocations of priest, doctor and judge. The priest, doctor and judge have to concentrate themselves in such a way on the tasks of the present that they must not be distracted by memories of former existences.

Tomberg, p 104 of this edition.

xv.

Cf. Reuben Parsons, in Studies in Church History, Vol. III, 1886, pp 200-201. Available here.

In 1487 Pope Innocent VIII condemned certain propositions defended by the celebrated John Pico della Mirandola. When only twenty-three years old, this philosopher and theologian had drawn from theology, physics, mathematics, magic, and cabalistics, a series of nine hundred propositions, which he offered to defend in Rome (y. 1486), “with all respect to the authority of the Church.” Some of these theses were very unorthodox, but the young disputant protested that he presented them only “for the sake of scholastic disputation, and subject to the correction of the Apostolic See.” About four hundred of the propositions were taken from Latin, Egyptian, Arabic, and Chaldaic philosophers; the others were opinions of his own. No one appeared to attack the theses, although Pico guaranteed all expenses of travel, etc. But the learned were irritated by his daring, and they presented to the Pope thirteen of the propositions as heretical, and after mature examination they were condemned. Pico defended them in several publications; and while, says Cantû, "we cannot derive a very clear notion of his meaning from his scholastic jargon, his task may be regarded as an attempt to reconcile Plato with Aristotle, and Pagan theology with the Mosaic and Christian.” In his Heptameron, Pico says: “Moses and the Prophets, Christ and the Apostles, Pythagoras and Plutarch, and in general, all the priests and philosophers of the ancient world, veiled their knowledge under images, because the crowd could not appreciate the truth, and understood what the words by no means indicated. It is certain that Moses, in his enumeration of the six days, did not speak of the creation of the visible world... Christ confided, in secrecy, certain truths to His disciples, and the knowledge of these truths is the great foundation of our faith;" and this knowledge can be acquired, insisted Pico, only by means of the Cabala. “Who does not see,” asks Canti, “whither such eclecticism leads? If it was applauded by the Academies and by the Medicean court, where such things were fashionable, it could not please Rome; and although Pico repeatedly protested his submission to the Church, he really substituted himself for the Church when he defined and explained dogma by means of Hebrew or the Cabala.” Innocent VIII said of Pico: “Let him write poetry; that is more consonant with his talent;” and although the Pontiff protected him from molestation, he would not withdraw his condemnation of the propositions.

Cf. also Fernand Mourret, History of the Catholic Church, Vol. V, pp 271. Mourret notes that Pico submitted to the condemnations of his ideas:

Giovanni Pico, of the princes of Mirandola and Concordia, was a precocious scholar who, at the early age of ten years, won renown as an orator and a poet, was admitted to the University of Bologna at the age of fourteen, and at the age of twenty-three challenged all the scholars of the world to a public discussion of 900 theses de omni re scibili. Pico was an adventurous scholar, dreaming of a revival of religion by a more critical study of the sacred texts and a more attentive comparison with ancient religions; he was also a daring thinker, affirming that sin, limited in time, can never merit eternal punishment, that Christ did not descend into hell save in a virtual manner, and that no science can better prove the divinity of Christ than magic.27 By a brief dated August 4th, I486, Innocent VIII condemned the 900 theses of Pico della Mirandola. The young scholar humbly submitted. A few years later he died, at the age of thirty-one, in one of his villas near Florence, at the very moment when, by the influence of Savonarola, he was disabused of the world's vanities and of human knowledge and was thinking of entering the Order of St. Dominic.

Mourret’s footnote at the end of this passage reads:

Pico della Mirandola, shortly before his death, addressed Alexander VI in a memoir containing an exposition of his personal views as to the condemned propositions. The Pope, in a special brief, assured him that he had never been judged guilty of personal or formal heresy. It has sometimes been maintained that Alexander VI thus contradicted his predecessor and approved the famous theses. (See Il Rosmini for 1889.) But this is a mistake. Alexander's brief exculpated Pico only from formal heresy, that is, personal and imputable, and approved only the ideas set forth in the memoir.

Cf. Trippi in Il papato, XXI, pp. 37 sqq., and Pastor, V, 344.

Cf. fn. 1 above.

The point that has been missed however is that it also amounts to Modernist Heresy

For a few minutes I was wondering if I had blundered into an unknown Monty Python sketch, with Roger Buck telling Morello that Valentin Tomberg (died 1973) has been acting as a "daemon" and guiding Morello. Plainly there are ever expanding layers of wackiness in this area of spirituality. McFadden should soon have enough material for a much expanded edition of his monograph. Indeed it might have grown to the length of a major book.