Eastern Orthodoxy? 'Some heterodoxies and inconsistencies'

One feature of the crisis in the Catholic Church is that some look East, and wonder if the 'Eastern Orthodox Churches' were right after all. Fr Reuben Parsons pours cold water on this romanticism.

Editors’ Notes

The recent enormities from Francis have prompted a number of helpful young ‘Orthodox’ men on the internet to call, mockingly, for Catholics to enter into their schism and heresy.

This is indeed a route which some have taken: it is evidently a temptation that some feel.

However, we need to be clear on the actual lay of the land.

The Roman Catholic Church is suffering an unprecedented crisis over the last 60 years or so, which is entirely explainable by the conclusion that the See of Rome has been vacant for that time. As a result of this vacancy, many heretics have been allowed to run riot and present their heresies as the teaching of the Church, without having been condemned or punished by law. This situation will be resolved when the See of Rome is filled.

The various ‘Orthodox’ churches have been suffering from an ongoing crisis over the last 1000 years or so, which is entirely explainable by their schism from the Church of Christ for that time. As a result of this schism, various heresies, heterodoxies, supine subjection to the state, surprising contradictions, and many other evils have proliferated, without having been condemned or punished by law. This situation will be resolved when both a) the See of Rome is filled, and b) the various heretical and schismatic sects submit to the Roman Pontiff.

In response to this, ‘Orthodox’ apologists appear to cry out:

“Look, you are just as bad as us, if not worse. You claims have been falsified. You might as well become like us!”

But as anyone can see, the two situations are not the same.

Further, if (per impossibile) the Catholic Church were to be “falsified,” it is certainly not the case that “Orthodoxy” would be proved true by default. Such an idea betrays a completely naturalistic understanding of the faith.

To illustrate this difference in greater detail, we are including Fr Reuben Parson’s article from The American Catholic Quarterly Review (Vol. XXV, Jan-Oct, 1900), entitled Some Heterodoxies and Inconsistencies of Russian ‘Orthodoxy.’ While it is primarily against Russian ‘Orthodoxy,’ many of its points are clearly applicable to the other similar sects.

No doubt this will offend or upset some of these enthusiastic adherents of ‘Orthodoxy,’ which we regret—particularly with regard to those whom we value as personal friends. This is published with no disrespect to them, or to the Russian people as a whole.

Nonetheless, in the face of those encouraging Roman Catholics to enter into schism and heresy, we publish this piece in good will, and in the hope that they will instead return to the Church of Christ, outside of which there is absolutely no salvation whatsoever.

See also:

Some Heterodoxies and Inconsistencies of Russian ‘Orthodoxy’

Fr Reuben Parsons

From The American Catholic Quarterly Review

Vol. XXV, Jan-Oct, 1900, pp 675-96.

Headings and some line breaks added by The WM Review

“They’re not heretics, they’re ‘merely schismatics’”

Not long ago an indubitably Catholic journal in one of our Western States, a journal which is not one of those weaklings which are so wanting in Catholic stamina and in proper knowledge that their demise would benefit the Catholic. cause, told its readers in an editorial that “the Russian Church is not heretical; it is merely schismatical.”

Such an assertion would not have been astounding, if emitted by that leading secular journal of the metropolis which, on the occasion of a recent attempt at theological excitement, showed that its religious editor was incapable of distinguishing the Immaculate Conception of the Blessed Virgin from the divine origin of Jesus, or from a supposed virginity of St. Ann.1

But so important an error on the part of a professedly Catholic journal, one which has shown itself to be well equipped for a defense of Catholic truth, and which has battled for that truth more successfully than very many other American Catholic organs, might add to the material for a future volume on “The Curiosities of American Catholic Literature,” were it not too true that similar misconceptions concerning the Greek Schism and its offshoots have found lodgment in the minds of perhaps the majority of our people. Russia, as well as the other lands where the spiritual progeny of Photius languishes, is very distant from us. Until recently very few of her sons came to our shores, and very few even of our more educated Americans have cared to know anything about the spiritual condition and the religious history of her children.

Then we have been accustomed to hear that the Russian Church “is almost Catholic;” or that “it is Catholic in everything, save the Pope;” or the real truth that “it has a true episcopate and a true priesthood, the Holy Mass and all the Seven Sacraments;” and the more simpleminded among us have come to believe implicitly, certainly not explicitly, that perhaps after all the poor Schismatics are about as well off spiritually as is the obedient flock of him to whom Our Lord and Saviour said: “Feed my sheep!”

Again, comparatively few among us have had anything like an accurate notion of the meaning of the word “Schism,” unless in its philological sense; and hence it seemed quite natural to think of a Russian as only or merely a Schismatic, one who might not be on the straight road which Christ indicated as leading to heaven, but who, at any rate, skirted the road, and who, with a little care, might avoid the ditches at its sides.

We heard, now and then, of some unfortunate priest who disobeyed his bishop, and who, followed by some poor ignoramuses or perhaps by some problematical Catholics, set up a little “Catholic Church” of his own. We pitied the poor schismatics, and in time we saw them all returning to the obedience of him who was commissioned by the Vicar of Christ; but in all such instances we failed to apprehend the deep significance of the term “Schismatic” in the sense in which it is applied to, and deserved by, the “separated churches of the East.”

In fact, the ‘Orthodox’ are indeed heretical

The great misery of all the Oriental Schismatic churches, including the Russian, the principal one, is found in the stubborn fact that each of them is historically and theologically heretical.

The poor man, or set of men, who simply refuse to obey the authority divinely established in the Church, may be merely schismatical; but they who absolutely deny the supremacy of the successors of Peter are heretics purely and simply, since they deny an article of Catholic faith.

Again, the “Orthodox” Russian Church is heretical because it denies the Catholic dogmas of the Procession of the Holy Ghost from the Father and from the Son; of the existence of Purgatory; of the Immaculate Conception of Our Lady; and of the Infallibility of the Roman Pontiff.

The time was when there was no great need for an accurate perception of this truth by the Catholics of this republic; but now that large numbers of Russian and Greek Schismatics are dwelling among us, too frequently mixing with our Catholic congregations, and not seldom causing dissension among them (whether as emissaries of the Holy Synod or not, we are unaware); now, we insist, our people should be taught the wicked absurdity of which they would be guilty, were they to palliate the heinousness of rending the seamless garment of Christ by the cherishing of such a thought as that expressed in the asseveration: “The Russian Church is merely schismatical.”

Reflections such as these have prompted us to dilate to some extent on the heterodoxies of which Russian “Orthodoxy” is culpable, and upon some of the flagrant inconsistencies into which its heretical blindness and obstinacy have led it.

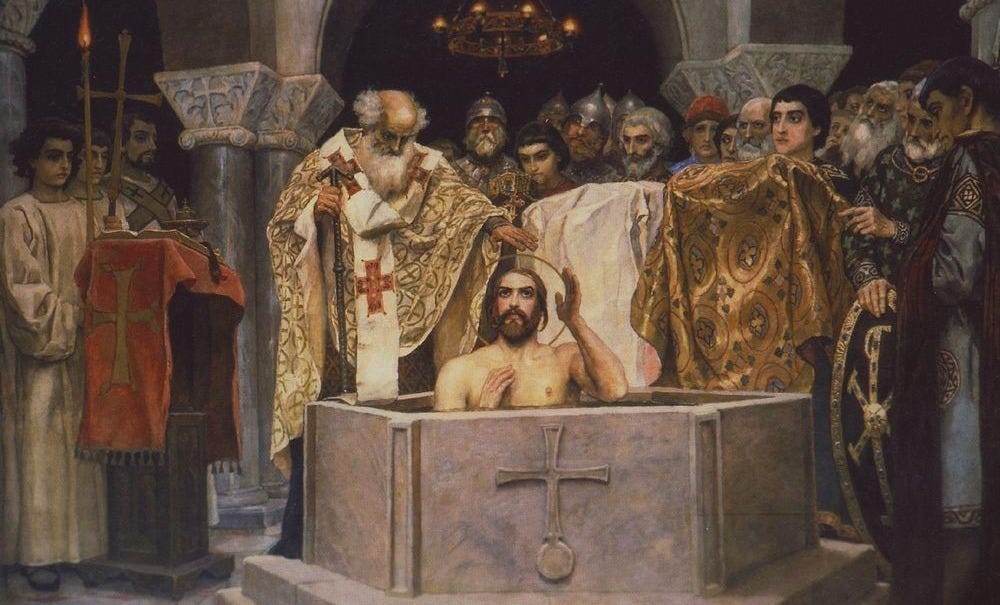

‘Orthodox’ internal confusion/contradiction over baptism

One of the principal grievances of Russian “Orthodoxy” against the Roman Church is found in the fact that the Mother Church administers the Sacrament of Baptism by “infusion” instead of by “immersion.” Both the “Orthodox” and the Constantinopolitan Schismatic theologies hold that immersion is probably of the very essence of valid baptism; and therefore, say all the separatist Eastern Christians, the efficacy of the Roman rite of baptism is at the best problematical. Thus, in the reply to Gagarin’s “Will Russia Become Catholic?” written by Karatheodori, physician to the Sultan of Turkey, under the title of “Orthodoxy and Popery,” we are told that “the baptism of the Latins is not a true baptism,” although, strangely admits the medical theologian, “it may be adopted in case of urgent necessity.”

The same doctrine, we are told by Gagarin, one of the most learned and judicious of the modern converts from the Russian Establishment, is inculcated in many works which have received the approbation of the Russian Holy Synod; and we know that after the rupture of the reunion of the Eastern Schismatics with the Catholic Church which the Council of Florence had effected in 1436, and after the deposition of Isidore, the Muscovite patriarch who had signed the Act of Reunion, his successor decreed:

“The Russians must rebaptize all Roman converts to their faith, since the Westerns baptize only by infusion, a condemnable practice which renders the rite null and void.”

Inconsistency in the application of rebaptism

But, strange to say, in the face of this opinion of the Holy “Orthodox” Church, and despite the tremendous importance of baptism in the minds of Russian theologians, it is not the custom of the “Orthodox” clergy to insist on a rebaptism, even on a conditional one, of such Catholics and Protestants as embrace the Photian Schism.

None of the German Protestant Princesses who enter the imperial Russian family, not even the one who becomes Czarina, is asked to submit to what “Orthodoxy” pronounces essential to her status as a Christian; she is simply required to declare her adhesion to the Holy “Orthodox” Church of Russia, even though there is very great probability that, owing to the not uncommon carelessness of Protestants in the essentials of the baptismal rite, the “converted” lady is a mere pagan.

The clergy of Holy Russia are not shaken out of their supineness by the fact that some day the possibly pagan Czarina, like that Princess of Anhalt-Zerbst who became the infamous Catharine II, may become in time the Russian Pope as supreme mistress of their Holy Synod; they know that the lubricious “Semiramis of the North” was not rebaptized when she married Peter III; and the fairly well-read among them know that Catharine avowed to the sycophantic philosophist, Voltaire, that the Russian Church does not rebaptize its converts from Catholicism or from Protestantism.2

In our own day there have been instances of wholesale so-called “conversions” to the Russian Establishment on the part of Polish Catholics, thanks to the knout, the bayonet, starvation, fear of Siberia, and, above all, to treachery and chicanery;3 and in no instance were these “converts” rebaptized, thanks to Peter the Great, the institutor of the Holy Synod, who by virtue of his autocratic power abrogated the decree of the Patriarch Jonas, thus opening to many a perhaps unbaptized Protestant the way to the priesthood and even the episcopate in the Russian Church.

It is worthy of remark that the more intellectual among the “Orthodox” clergy have frequently appreciated the significance of this inconsistency, especially when they reflected on the more consistent practice of the clergy of the Constantinopolitan Schismatic Patriarchate, from which they pretend to derive their origin, and with which they communicate; they have endeavored to explain away the contradiction in a very curious fashion. Thus, in the Causérie Ecclesiastique, a periodical published by the Ecclesiastical Academy of St. Petersburg under the very eyes of the Holy Synod, we read in the issue of September 17, 1866:

“The Greek Church (Schismatic) admits willingly the validity of baptism given by infusion; but it demands from converted Latins a new baptism in order that it may draw a well-defined line of demarcation between the Greeks and the Latins—in fact, the Greek Church so dreads a possible reconciliation with Rome that it has thought it wise to make the Greeks believe that the Latins are in no sense Christians.”

It is amusing to note that the famous William Palmer,4 while still involved in the mazes of the English Royal Establishment, discovered that if he wished to become a Constantinopolitan Schismatic a trip to St. Petersburg would dispense him from a rebaptism.

“There is a way out of the difficulty,” he wrote; “a trip to St. Petersburg will settle the matter. I can join the Russian Church without being rebaptized; then I can go to Constantinople, and since the ‘Orthodox’ and the Greek (Schismatic) Churches communicate, I can be admitted to the sacraments and even to the priesthood at the hands of His Greek Œcumenicity.”5

Chaos in relation to dissolubility of matrimony

No less striking than that in reference to baptism is the inconsistency of the Russian “Orthodox” Church in regard to the dissolubility of matrimony.

According to the olden doctrine of that Church, just as according to that of its pretended source, the Schismatic Greek Church, a consummated Christian marriage can be dissolved only because of adultery; but in practice there are now one hundred and ninety-five cases in which the tie of marriage may be nullified.

One of the most interesting modern instances of this flagrant inconsistency was that of the divorce of the Grand Duke Constantine, brother of Alexander I, from his wife, Anna Feodorowna. Not a soul breathed a word against the matrimonial fidelity of the Princess; the state of her health compelled her to live apart from her husband; and he had fallen in love with the Countess Grudzinska. On March 20 (April 2), 1820, Alexander I made known to all his subjects that the Holy Synod,

“relying on the precise text of the thirty-fifth Canon of St. Basil the Great, declared that the marriage of the Grand Duke and Czarwitch, Constantine Paulowitch, with the Grand Duchess, Anna Feodorowna, was dissolved, and that he was free to contract a new marriage.”

Marriage continued — the counter-example of St. Theodore Studita

It would be interesting to know how many members of this Holy Synod, this servile creature of the autocrat, were acquainted with the life of one of the glories of the Greek Church—St. Theodore Studita, who flourished at a period when the Eastern Churches were still devotedly attached to the communion of the Apostolic See.

When the Greek Emperor, Constantine VI (Porphrogenitus), having discarded his wife and contracted a “marriage” with his concubine, Theodota, was upheld by a conciliabulum of courtier prelates like those who are the slaves of the Protasoffs, etc., of our day, Theodore protested against the legalized adultery, and from his dungeon he wrote to the Father of the Faithful, Pope St. Leo III:

“Since Our Lord Jesus Christ confided the keys of the Kingdom of Heaven to Peter, and afterward conferred on him the dignity of Prince of the Apostles, it is our duty to make known to the successor of Peter such innovations as are introduced into the Church of God…

“Oh divine superior of all superiors! There has been formed here, according to the expression of Jeremiah, an assembly of prevaricators and a meeting of adulterers.”

But the members of the Holy Synod were then, as they have ever been and still are, of calibre diametrically contrary to that of the Studita; as for the support which they pretended to find in a Canon of St. Basil, it is evident that just as in the case of the Grand Duke there was no question of adultery, so in the adduced canon there was no question of divorce, but simply one of a more or less grave ecclesiastical censure to be visited on spouses who separated “from bed and board.”6

But instances like this of Constantine Paulowitch are in significant when compared with the consequences of a ukase of Nicholas I permitting new marriages to all Catholic wives whose husbands had been sent or would be sent to Siberia, to prison, or to forced labor in the mines-providing, of course, that they would promise to raise their children, future and already born, in the Church of the State.

The reader who accompanied us in our investigations into the martyrdom of Poland from the days of Voltaire’s “St. Catharine” to the advent of the present Czar, and who is therefore able to appreciate the iniquities of the great majority of the “criminals” who have languished in Russian penal establishments, will understand how widespread would have been the desolation if most of the Polish women had not been worthy of their Catholic ancestors.

We would merely note that by the provisions of his matrimonial ukase Nicholas I simply enforced the principles of modern Liberalism regarding the competency of the State, and the incompetency of the Church, in matrimonial causes—principles which an American proconsul has recently actuated in Cuba, in illustration of the beauties of a new “civilization,” and which were interpreted for the benefit of Pope Gregory XVI by Count Gourieff, Russian Ambassador at the Vatican, when in a memorial ad hoc presented to the Pontiff in May, 1833, he impudently asserted that

“the pretensions of the Catholic Church in regard to matrimony constitute an attack on the prerogatives of the State, and that the efforts of the Roman Court in behalf of those pretensions are mere attempts to actuate certain enactments of ancient Councils which have now fallen into desuetude.”

Such inanities as these of the little diplomat call for no attention. Let us rather use some of our limited space for a few observations on the manner in which the Canon Law of “Orthodoxy” came to recognize the one hundred and ninety-five causes for dissolution of matrimony which are unknown to the Divine and to the original Russian Ecclesiastical Law.

195 causes for divorce in the ‘Orthodox’ schism — ‘Church’ supine before the civil power

In every age of the Christian era, just as in the days of the Old Law and of Gentile Paganism, the conflict between the ecclesiastical and the civil power has been perennial; and such it will be until the end of time, since the average human ruler will ever refuse to act as though he recognized that between him and his subjects there is always extended the ordaining and guiding hand of God.

Rulers like Charlemagne, St. Edward, St. Louis IX and Garcia Moreno are seldom granted, even to Christian peoples.

Thus the Eastern Emperors, even while the Eastern Patriarchates were still devotedly bound to the Chair of Peter in ecclesiastical and filial communion, frequently pretended to a right to arrange matrimonial causes according to their momentary whims. Justinian, by his Novella 117, admitted six reasons for divorce in favor of a husband and five in favor of a wife, in spite of the fact that even the Eastern Church, when it mistakenly relied on a false interpretation of certain verses of St. Matthew, allowed divorce only in the case of adultery.

Then, just as in later days in the case of the United Greeks, the Holy See could only protest, and exclaim: “Ipsi viderint.” But the condemnation was launched against this violation of the law of God, and the obstinate and puerile Orientals could enjoy such satisfaction as may be derived from continuing a practice which is reprobated by the Vicar of Christ.

In time the sins of the Lower Empire merited for it the usurpation of Photius, the imperial sword-bearer; and when governmental brute force had detached the Constantinopolitan Patriarchate from the communion of the Catholic Church, the intruder compiled a new code of Canon Law which he designated as a Nomocanon, and in which he incorporated all the Novellæ of Justinian. From that day the canonists of the Constantinopolitan Schism, and those of all the derivatives of that Schism, have accorded a place, aye, even the first place, to the matrimonial ordinances of a civil government.

Nor should we forget that Photius augmented the matrimonial consequences of the Justinian Novella by the addition of three new causes for divorce; for that matter, the Canon Law of the Wallachian Greek Schismatics admits three others. And we must note that the most recent Collection of Canon Law received by the Schismatic Greeks, the one compiled by Rhalli, the president of the Athenian Areopagus, under the auspices of the Holy Synod of the governmental Hellenic Church (1856), opens with the Nomocanon of the disreputable Photius, and eulogizes the reprobate in most extravagant terms.

From these observations the reader will understand the readiness with which the Holy Synod recognized the Nicholaite one hundred and ninety-five causes for the dissolution of the matrimonial tie, when it failed to breathe a word of disapproval of them, and allowed the “Orthodox” clergy to bless the unions which were contracted in accordance with the imperial dispensations.

It is true that these privileges of Satan were ostensibly granted to the Poles alone; but we fail to comprehend how an autocrat can possess religious jurisdiction over one portion of his “thrice blessed subjects,” and not over all of them. Nor can it be said that the case of the hundred and ninety-five dissolving causes was a matter of the civil law. In Russia the civil and the ecclesiastical law emanate from the same source; the civil and ecclesiastical autocrat cannot be supposed to regard his civil and his ecclesiastical enactments as mutually destructive; and when the “Orthodox” priests perform a religious rite with the consent of the Holy Synod, that tribunal must be supposed to approve the act.7

However, we cannot drop this subject of Russian Cesarian usurpation in matters of matrimony without an admission that in our day there have been many abuses by Polish Catholics in the matter of divorce; there have been adduced nullifying reasons which were deliberately ignored by the contracting parties at the time of the marriages. But we must remember that in the premises there is one great difference between the conduct of the “Orthodox” Schismatics and that of the Catholic Church, namely, the protestation which the latter, when suffering because of human passions, never fails to emit.

The Catholic Church is never derelict in this matter, even though the blood of her bishops and priests must necessarily flow in consequence of her steadfastness. In 1830, when Poland still had a semblance of a National Diet, that assembly heard the courageous protests of the Polish bishops against the frequent violations of the Ecclesiastical Canons in matrimonial causes, and it was in spite of those protests that supposedly nullifying reasons were relegated to the consideration of the civil tribunals, and that the apostolic zeal of Gutkowski, Bishop of Podlachia, and of Skorkowski, Bishop of Cracow, entailed upon them dismissal from the capital before the dissolution of the Diet.

A trivial accusation against Latins

The great “reformer” of the Muscovite Church, and also its greatest robber, was the Czar, Ivan the Terrible; and according to him the foulest error of the “Western heretics” was the shaving of the beard. In an edict which this Head of the “Orthodox” Church issued in 1551, being unaware that another Russian Supreme Pontiff, the “great” Peter, would one day enact the contrary, he proclaimed that “the effusion of a martyr’s blood would not atone for this crime.” [Of shaving the beard.]

The Filioque – ‘Orthodox’ actions inconsistent with words

However, with all due respect to the memory of the terrible Ivan, the modern clergy of Holy Russia agree with their cousins of the Schismatic Constantinopolitan Patriarchate and with the derivative Churches of that separatist organization, in the declaration that the prime justification of the Photian rebellion must be found in the fact that the Roman Pontiffs had confirmed the “heretical” teaching according to which the Holy Ghost proceeds from the Father and from the Son.

In fact, the doctrine that the Holy Ghost proceeds from the Father alone is the cardinal dogma of the “Orthodox” belief. And nevertheless, in the most important official act which the Russian Establishment has performed in modern times, namely, the declaration of the Holy Synod dated March 25, 1839, whereby certain apostates from Catholicism, certain United Greek bishops of Lithuania, were received into the communion of the Russian Establishment, no recantation of “the most damnable Latin heresy” was demanded from the “converts.”

The sole requisite for an admission to the yearning embrace of Holy Russia was a renunciation of obedience to the Pope of Rome.

Listen to the text of the Synodal declaration:

“Their solemn profession that Our Lord and God, Jesus Christ, is alone the veritable Head of the One and True Church, and their promise to persevere in unity with the holy orthodox patriarchs of the East and with this Holy Synod, leave nothing for us to demand from these members of the United Greek Church in order to effect their true and essential union in the faith; and therefore nothing prohibits their hierarchical reunion with us. Therefore the Holy Synod, by virtue of the grace and power given to it by God the Father, by Our Saviour Jesus Christ and by the Holy Ghost, has resolved and decreed,” etc.

And then the Holy Synod warns the “converted” prelates not to trouble their flocks, whom they hoped to drag with themselves into the vortex of the schism, with questions of mere “local significance,” things which “involve neither dogma nor sacraments.”

Can it be that the Holy Synod would have asked the innocent and ignorant to believe that an exterior and public manifestation of the nature of the belief in the Procession of the Holy Ghost was a mere matter of “local significance, which involved no dogma?” Truly this act of the Holy Synod was both cowardly and (according to its faith, if it had any) sacrilegious; and when the brigandage of Chelm, which we have elsewhere described, almost destroyed the remnants of the United Greek Church in Russia, there was observed what the powers of darkness must have regarded as the same “prudent silence.”

How different this course from that pursued by the Holy, Roman, Catholic and Apostolic Church, which receives no convert into its pale, let the person be ever so humble or ever so exalted, until he or she has abjured not only every dogmatic error in general, but also the specific errors of the forsaken creed!

Purgatory – hypocrisy on the part of ‘Orthodox’ opponents

Plato, metropolitan of Moscow, probably the most illustrious churchman whom Russian “Orthodoxy” has produced during the nineteenth century, was once asked by a Western concerning the teaching of his Church on Purgatory; and the prelate replied:

“We reject the doctrine of Purgatory as a modern invention, excogitated probably for the sake of money.”8

And this assertion, a delectable morsel for the average Protestant, is dinned into the ears of every “Orthodox” student, despite the notorious fact that almost the principal revenue of the Russian priests is derived from prayers for the dead, and although the Russian “Particular Catechism,” the work of Philarete, metropolitan of Moscow, inculcates the propriety and even the necessity of that practice.

Anti-intellectual contrarian attitudes to the Immaculate Conception

Not the least strange among the inconsistencies of Russian “Orthodoxy” is the hostility which it manifested toward the definition of the dogma of the Immaculate Conception of Our Lady; it is strange indeed, since the principal monuments of the Eastern Church are so redolent of testimonies in favor of the doctrine, that it may well be said that if Pius IX had proclaimed its contrary, the Holy Synod would have denounced him as a heretic ex alio capite.

However, the author of “Orthodoxy and Popery” avers that in the dogmatic definition of Mary’s great prerogative, the Roman Church “manifested its unbridled love of change, of movement, and of innovations in the domain of a faith which is eternally unchangeable by its very nature.” And, nevertheless, this author tells us that according to the Eastern Church the Blessed Virgin “was exempt from the effects of original sin”—an avowal which is so true, that any reader of the Bull Ineffabilis Deus will perceive that His Holiness relies chiefly on the testimony of the Eastern Fathers for the establishment of his thesis.

This same “Orthodox” author knew very well that one of the chief complaints of the Russian Starovere heretics against the Holy Synod is to the effect that this would-be authoritative tribunal renounced, in 1655, the ancient belief of the Christian East in the Immaculate Conception of the Mother of God. The same author must have remembered that in the seventeenth century the ecclesiastical Academy of Kiev, speaking through Lazarus Baranowitch, Bishop of Tchernigow, regarded that doctrine as indubitably true;9 and we can scarcely imagine that the Academy could have deemed otherwise when it was accustomed to hear, among other and innumerable evidences furnished by the Russian Liturgy, that passage of the Office for the Nativity of the Virgin:

“We proclaim and celebrate thy birth, and we honor thy Immaculate Conception.”

Self-confessed ‘Orthodox’ laxity and sacrilege with respect to the confessional seal

We shall merely touch the manner with which the “Orthodox” Church treats the secret of the confessional.

The awfulness of the subject, and the notoriousness of the sins of “Orthodoxy” in this regard, excuse us from dilation on the matter. In 1854 Snagoano, a Greek archimandrite, who gloried in his communion with “the holy patriarchs of the Orient,” published in Paris a work on “The Religious Question in the East,” from which we cull the following passages:

“The Russian Church is simply a schism, because it has separated from the great Eastern Church; because it does not recognize the Patriarch of Constantinople as its head; because it does not receive the Holy Unction from Byzantium; because it is ruled by a Synod, over which the Czar is a despot… and because Confession, instituted for the betterment and the salvation of penitents, has become, through the servility of the Muscovite clergy, a mere instrument of espionage in the interest of Czarism.”

That this accusation is well founded has been demonstrated for the enlightenment of those who have had no extensive experience in Russia, by Tondini10 and by the “Orthodox” author of “The Raskol.”11 The latter writer tells us that

“there is an ordinance which compels each priest to reveal to the government every plot against it which may come to his knowledge in the confessional.”

And this ordinance is in accordance with a ukase issued by Peter “the Great” on February 17, 1722, enjoining the taking of the following oath upon every priest of the “Orthodox” Church:

“I will denounce and reveal (all conspiracies) with entire truthfulness and without any disguise or palliation, having in my mind the fear of losing my honor and my life.”

Certainly the term “inconsistency” is too mild to serve as a qualification of such sacrilege on the part of the priests of a Church which holds, at least theoretically, the same views concerning Sacramental Confession that are taught by the Church of Rome.

However, this abject cowardice and diabolical treachery is but natural in an organization in which the civil power takes no pains to disguise its tyranny over the ecclesiastical, and in which the clergy manifest no shame because of their groveling, but rather consider it a matter of course that they should give to the autocrat the blind obedience of a soldier.

How the Orthodox Church acts when in conflict with civil authority

The “Orthodox” Church claims to be a divinely instituted organization, empowered to labor for the eternal salvation of men, and resolved to accomplish its task in spite of the influence of earthly power, when that power is hostile to its objects. Did it not claim such origin, endowment, and intention, it could not present itself as the Church of God. We pass, for the present, the matter of the origin of the Russian Ecclesiastical Establishment; now we would briefly consider its course when it finds itself confronted by the civil power.

“It would be easy,” remarks Lescœur, “and it has been done a thousand times, to multiply proofs of the absolute degradation of the Russian sacerdotal order in its relations with the government.

“Were we to examine all the grades of the hierarchy, from the pretended Holy Synod which is servile when it is silent, and more servile when it speaks, down to the humblest village pope; from the Universities and the privileged convents where are trained the few distinguished governmental candidates for bishoprics, or for diplomatic posts, or for the general run of the public offices, down to the miserable convents of men or of women, in which there languish wretched beings without piety or charity, and which are inevitably homes of ignorance and vice; everywhere we would find the same conditions produced by the same cause-the subordination, or rather the absolute effacement of the religious element, absorbed by the civil power.”12

‘Orthodox’ hierarchy will protestantise itself at the behest of civil power

Even in purely theological matters, the “Orthodox” episcopate and priesthood have seldom or never been able, if willing in rare instances, to withstand the governmental pressure. When Peter “the Great,” following the counsels of the Genevan, Lefort, to whom he owed the invention of the Holy Synod, tried to demi-Protestantize his Church, he found his clergy, his seminarians, and even his bishops, so subservient, that when the Lutheran, Frederick Lütiens, dedicated his curious book to the Grand Duke Peter Feodorowitch (afterward Peter III) he felt justified in congratulating the Prince and his bride (the future Catharine II) on the fact that

“the glorious Peter had so restored and modified the modern religion of the Russians in accordance with the Scriptures and with the rules of the primitive Church, that he had made it as similar as possible to that of the Evangelico-Lutherans.”13

And the Lutheran was able to support his assertion by quoting the text of the Catechism which had been compiled by the “Orthodox” bishop, Theopanes Procopowitch, the prelate whom Peter “the Great” had employed to draw up his “Ecclesiastical Regulation.” In this Catechism, declared Lütiens,

“we find the purest Evangelical doctrine on the forgiveness of sin, on justification, and on the eternal salvation which is attained by faith in Jesus Christ alone.”14

And when, in 1807, the court of St. Petersburg had tired of its playing with Protestantism, and felt the necessity of resuming its comparatively closer connection with the primitive Church, did it turn to its bishops for the accomplishment of the restoration? By no means. The imperial “supreme judge of the Holy Synod” appointed a mixed commission of ecclesiastics and laymen, according to it absolute control over the curriculum of each seminary; and in this commission there were numbered merely a few bishops, and they were all favorites of the court.15

But the Holy Synod perceived no insult to itself, no usurpation of the things of the sanctuary, in this imperial pretension; it was as ready then to abrogate every ecclesiastical prerogative as it was in 1830, when, in order to aid in the final destruction of agonizing Catholic Poland, it took from the seminaries 20,000 seminarians, declared them forever debarred from the priesthood, incorporated them into the army, and sent them to evangelize the Poles in the fashion which we have seen recommended and adopted by Siemaszko.16

Absolute abjection of the ‘Church’ to the civil power, even in minutiae

There is one instance of abjection, however, on the part of the “Orthodox” clergy, which perhaps speaks more eloquently than those which we have indicated. In every Russian liturgical service at which the litanies are recited, not only the name of the Czar, but that of the last little baby of the imperial family, is mentioned before the existence of the Holy Synod is recognized.

But hearken to a few of the abject phrases used by the Holy Synod; we cull them at random from some acts of the tribunal:

“Conformably to the most exalted will of His Majesty, the Holy Synod has undertaken to better the condition of the provincial clergy—By order from above, many monasteries have been deprived of their rights of fishing—The bishop of Kursk is allowed to print his sermons—His Majesty has found it wise to dissolve the Commission for Ecclesiastical Schools, and to confide their direction to the Holy Synod, charging the supreme procurator (always a layman, and generally a soldier) with the execution of its orders—By a decision of the Imperial Council, confirmed by His Majesty, the marriage of [——] a pagan, with [——], a Mussulman, is pronounced valid, provided that the latter receives Baptism—We humbly beg Your Majesty to assure the salvation of the United Greeks by allowing them to join the Orthodox Church of All the Russias.”

It is not surprising that Voltaire, after feasting on such fulsomeness as exhales from these and similar phrases, should write to his “saint,” the Messalina of St. Petersburg:

“As for me, Madame, I am faithful to the Greek Church (Voltaire was very weak in historical knowledge), and so much the more since in a certain sense your beautiful hands swing its thurible, and since you may be regarded as the Patriarch of All the Russias.”17

Nor can we wonder that among the many millions of Russian dissidents who to-day despise the authority of the official Church, who await an opportunity to combat it à l’outrance, and who hate the Catholic Church with a venom almost equal to that expressed by the Holy Synod, by far the greater number find the sole justification of their revolt in the really unchristian dependence of “Orthodoxy” on an earthly power.

“For a long time,” remarks Gagarin, “the bosom of the Russian Church has been lacerated by dissident sects, but the development of these to-day is immense; between fifteen and eighteen millions are enrolled under their standard.”18

The “Orthodox” author of “The Raskol” says that the Raskolniks

“confound the temporal sovereign with the head of the Church (and why not?), and therefore they are in a state of perpetual, although latent, war with the laws of the land. They excommunicate the Czar; they style him Antichrist.”19

The very existence of the ‘Holy Synod’

Now for a few reflections concerning the Holy Synod, the presumed authoritative voice of Russian “Orthodoxy;” we shall see that the very existence of this tribunal is both an inconsistency and a heterodoxy. We have noted that the author of “Orthodoxy and Popery” reproves the Roman See for an alleged “insatiable yearning for religious innovations;” and it is notorious that the “Orthodox” have always prided themselves on the immobility of their Church, even when they were obliged to ignore the fact that with them immutability and lethargy are generally synonymous.

But can the “Orthodox” show us, we will not say any Scriptural foundation, but rather any Eastern tradition-—any Eastern conciliar or patristic warrant for the existence of this Holy Synod? Is it not a matter of cold history that this body is much less than two centuries old? And can any student deny that from its very creation it has been the docile instrument of innovations at once anti-canonical and scandalous?

Has the Roman Pontiff, whose alleged “omnipotence” is denounced as strenuously by the “Orthodox” as by the Anglicans and other Protestant sectarians, ever attempted to change the essential form of ecclesiastical government; has he ever dared to suppress anything in this line that the Apostles prescribed; has he ever presumed to substitute a cardinalitial, episcopal, presbyteral, or civil governmental régime for that monarchical primacy of Peter alone which all his predecessors declared to be of divine institution?

Ecclesiological innovations and impudence

But this most fundamental of all innovations the Russian Czarate effected, without any efficacious or even serious protest on the part of the “Orthodox” hierarchy, when it instituted the Holy Synod. In the “Particular Catechism” of the Russian Church the sublimity of impudence is reached when, on page 68, to the question as to “what ecclesiastical authority rules the principal divisions of the Universal Church,” the following answer is given:

“The orthodox patriarchs of the East and the Synod of Russia, the order of hierarchical precedence being, 1st, Constantinople; 2nd, Alexandria; 3rd, Antioch; 4th, Jerusalem; 5th, the Patriarchate or Synod of Russia.”

And then to the question as to the rank of the Holy Synod, the reply is:

“The Synod has the rank of a patriarch, since it takes the place of the Patriarchate of Russia which was abolished with the consent of the other patriarchs.”

The more than implication that there is no such thing as the Patriarchate of Rome; that the Church of God is peculiarly an Oriental Church; was probably very acceptable to the simple “Orthodox” who received as Gospel truth the lessons in history which Nicholas I gave to his subjects when he decreed that in all the educational institutions of his empire the qualification of “tyrant” should never be given to Nero, Caligula, or Ivan the Terrible; that no teacher should dare inform his pupils. that the House of Romanoff became extinct in 1761 in the person of the Empress Elizabeth, and that it was the foreign family of Holstein-Gottorp which then (as now) held the czarate; that every pedagogue should insist that the reigning autocrat descended in direct line from Rurick of Moscow; and that the reason for the preference of the ancient Romans for a republic is to be found in the fact that “they had not the good fortune of being acquainted with the blessings which are entailed by the rule of an autocrat.”20

State presuming to abolish ecclesiastical institutions

As for the implied falsehood that the consent of the Oriental patriarchs to the establishment of the Holy Synod was both seriously asked and freely accorded, we reply that granted this seriousness and this freedom, the prelates in question had no power to change the patriarchal constitution of their churches; and, furthermore, that there is good reason to believe that at least the patriarchate of Constantinople afterward withdrew its consent. This we are led to believe from the words of the well-informed Greek archimandrite, Snagoano, who added to the already cited anathema against “Orthodoxy” the following indictment:

“Since the impieties of this Synod are so signal, who will dare to assert that the Russian Church is not schismatical? It is rejected by the Councils; the Canons forbid its recognition; the Church spurns it, and all who hold the faith of the Church, and whom the Church acknowledges as her children, must respect her decisions and regard the Russian Rite as schismatical.”

However, even if we hold that the Oriental patriarchs could and did abolish the Russian patriarchate, we cannot forget that the constitution of the Holy Synod destroyed the episcopal authority, a thing of divine institution, as to its very essence; that it left the Russian bishops that episcopal character which is God-given, and which no Synod could efface, but that it left them no more authority than that exercised by the unconsecrated Methodists, Episcopalians, Moravians and such like, who merely parade an empty episcopal title.

The Greek Fathers would not accept ‘Orthodox’ indignity

But what would the Greek Fathers have thought of this assembly composed of nominees of an emperor, men who were movable at his caprice?21 Listen, for instance, to that St. John Damascene whom the “Orthodox” are so fond of quoting in fancied support of their theory concerning the Procession:

“The emperors have no right to give laws to the Church. Hearken to the words of the Apostle: The Lord has established Apostles, prophets, pastors and teachers. He says nothing about emperors.”22

And what would St. Athanasius say?

“If the bishops so decree, why do you speak of the emperor? When did an episcopal decree derive any authority from an emperor; when was such a decree regarded as an imperial decree? Long before our day many synods have been assembled and many decrees have been published by the Church; but the Fathers never consulted the emperors, the emperors never examined into ecclesiastical matters. St. Paul had friends among the familiars of Cæsar; but he never admitted them into his councils.”23

Bishops of the calibre of Sts. John Damascene and Athanasius would scarcely have submitted the results of their deliberations to the judgment of a colonel of hussars, himself the creature of a temporal ruler.

But this temporal ruler must fain talk in pontifical fashion when he institutes his new secretariate. In 1720, announcing to his subjects the great blessing about to accrue to them, Peter the “Great” thus perorated:

“Amid the innumerable cares which are entailed upon us by the supreme power which has been given to us by God, we have cast our regards on ecclesiastical affairs in order to reform our people and the kingdoms subject to our empire; and we have discovered grave disorders, as well as many faults of administration.

“This fact filled our conscience with legitimate fear lest we would prove ungrateful to the Most High, if, after having effected, through His aid, such happy reforms in the military and civil orders, we neglected (mark the logical sequence of ideas) to exert ourselves to the utmost in order to restore sacred affairs to their highest perfection and their greatest glory.

“Therefore, following the example of those monarchs of both the Old and the New Testament whose piety was so illustrious,24 we have determined to improve the present condition of sacred things.”

The oath to be taken by the members of the Synod

And observe the eloquent significance of the oath which each member of the Holy Synod takes on his installation:

“I avow and affirm under oath that the supreme judge of this Synod is our monarch, the Most Clement (listen, spirits of Polish martyrs!) Emperor of All the Russias.”25

It is a remarkable fact, observes Tondini, that this avowal of dependence on the Czar—a dependence so utterly incomepatible with the Gospel and so repugnant to the honest student of ecclesiastical history—is not demanded from the members of other Russian tribunals.

“The framer of the oath knew what he wanted,” says Tondini; “he wanted docile prelates, and he gained his point, thus proving, as he himself boasted, that he was greater than Louis XIV.”

The disgraceful history of Photius

Before we treat of the prime inconsistency of Russian “Orthodoxy,” its rejection of the supremacy of the Roman Pontiff, it may be well to notice another inconsistency which it manifests in regard to the instigator of the Greek Schism.

Prince Augustine Galitzin, in his valuable work on the “Orthodox” Church,26 remarks that

“the origin of the Schism was so disgraceful that it dares not venerate its founder, whereas, among its thousand other contradictions, it joins the Universal Church on October 23 in celebrating the Feast of St. Ignatius (patriarch of Constantinople), the first victim of Photius.”27

It is true that individual writers of the Russian Church and of the Schismatic Constantinopolitan Patriarchate have been sufficiently audacious to describe Photius as of “happy memory;” and some have ventured to quote his letters to Pope Nicholas I as models of piety, brazenly ignoring his deposition of his legitimate patriarch and his violent occupation of the patriarchal throne after a reception of Orders per saltum—of all, from tonsure to the episcopacy, in the space of six days.

Sincerity could not have been characteristic of a prelate who, when prepared to forswear his allegiance to the Holy See, nevertheless wrote to the Pontiff in the following strain, so long as he conceived it possible that Rome might countenance sacrilege and ecclesiastical intrusion:

“My predecessor having resigned his dignity, the assembled metropolitans, the clergy and, above all, the emperor, who is so kind to others but so cruel to me, impelled by I know not what idea, turned to me, and paying no attention to my prayers, insisted that I should assume the episcopate; in fact, in spite of the tears of my despair, they seized me and executed their will upon me.”

Why ‘Orthodox’ opposition to the papacy is nonsensical

As is well observed by Lescœur, if the “Orthodox” theologians have frequently fluctuated between the Church and Protestantism, according to the spirit of the times, and especially according as the imperial will has inclined for the nonce, there is one doctrine concerning which they are frankly Protestant.

“When one hears the theologians of the Holy Synod declaiming against Popery, he might believe himself in London or in Geneva; but when he beholds the measures, sometimes petty and often barbarous, with which all recourse to Rome is either prevented or punished, he recognizes that he is in Russia. The Poles know full well that it is more dangerous to be a Papist frankly in Warsaw than it is to be a Raskolnik in Moscow.”

And nevertheless-and here we approach the chief, the most radical inconsistency, and the raison d’être of every heresy which afflicts “Orthodoxy”—a Russian cannot consult the Liturgy of his own Church, or celebrate the feasts which that Liturgy prescribes, or peruse the most authoritative books of devotion recommended by his spiritual advisers, without being confronted in bold relief, as it were, by St. Peter proclaiming his prerogatives, and by the entire body of doctrine which the Roman See teaches to the world.

The cultivated Russian cannot escape the knowledge that the Church of Constantinople, from which, as he believes, his ancestors received Christianity, was at that time subject to the See of Rome, or was, as moderns are fond of saying, Roman Catholic.

He knows that originally his “Orthodox” Church was far more Roman than Greek; that his Church was not Schismatic Greek in its origin, and that it is not Greek in its language, its polity, or its government.

History tells him that his ancestors were converted by the Roman Catholic Apostolic Church; for whether, as we learn from Constantine Porphyrogenitus, the first missionaries to Russia were sent by the Catholic patriarch of Constantinople, Ignatius, in 867, or, as Nestor asserts, by the schismatic intruder, Photius, in 866, it is certain that no real impression was made upon the Russian masses before the close of the tenth century,28 when the Grand Duke Vladimar, called “the Apostolic,” embraced Christianity—an epoch at which the Greeks were in communion with Rome, for the properly so-called Photian Schism had ended with the second and final deposition of the intruder in 889, and the Constantinopolitan Patriarchate remained subject thenceforward to the Holy See until the definitive actuation of the Greek Schism by Cerularius in 1054.

Our cultivated Russian knows also that the definitive defection of the Greeks did not much affect the relations of his countrymen with the Papacy until the twelfth century; that only then they were seduced entirely from the Roman obedience; that a reaction having taken place, by the time that the Council of Florence was held (1439) there were as many Catholics as Schismatics in Russia;29 and that it was a second Photius, Archbishop of Kiev, who extended the Schism throughout the land about the middle of the fifteenth century.30

Nor will our well-informed Russian fail to realize that his Church is not Greek in its liturgical language; that this language is the Slavonic, and not the vernacular, but the Old Slavonic, with which the people are not familiar.31

Again, this unbiased Russian will learn from the monuments of his own “Orthodox” Church that the Papal supremacy over the Constantinopolitan Patriarchate or, as it was at that time not improperly termed, the Greek Church, dates from the first day of that patriarchate’s existence.

He must feel that if obedience to the See of Peter had not been part of the faith of all the Oriental Patriarchates when Photius started the Greek Schism on its first stage, that desperate intruder would not have troubled himself so exceedingly to obtain the Pontifical confirmation of his sacrilegious and all but murderous seizure of the Constantinopolitan crozier.

Quite naturally he must reason in the same manner when he thinks of Cerularius, who separated definitively the greater number of the Eastern Christians from the communion of Rome.

He must ask himself how it is, in the supposition that his own “Orthodox” Church was not Roman in its origin, that his Church celebrates so many feasts which Rome prescribes, but which the Schismatic Greeks reject?

And finally he must wonder how it happens that if the Russian Church did not in its early days proclaim the supremacy of the Roman Pontiff, nevertheless the ancient “Orthodox” Liturgy avows that supremacy in terms which admit of no exception on the part of a Catholic theologian.

The evidence of the Byzantine Liturgy for the papacy ignored

For instance, St. Peter is termed “the sovereign pastor of all the Apostles—pastyr vladytchnyi vsich Apostolov.” Pope St. Sylvester is called “the divine head of the holy bishops.”32

We read of Pope St. Celestine I that “firm in his speech and in his works, and following in the traces of the Apostles, he showed himself worthy of occupying the Holy Chair by the decree with which he deposed the impious Nestorius (patriarch of Contantinople).”

It is said of Pope St. Agapetus that “he deposed the heretical Anthimius (another patriarch of Constantinople), anathematized him, and consecrating Mennas, whose doctrine was irreproachable, placed him in the See of Constantinople.”

Similarly we hear of Pope St. Martin . that he “adorned the divine throne of Peter, and holding the Church upright on this rock which cannot be shaken, he honored his name;” and this praise is given to St. Martin because “he segregated Cyrus (patriarch of Alexandria), Sergius (another patriarch of Constantinople), Pyrrhus and all their adherents from the Church.”

Pope St. Leo I is styled “the successor of St. Peter on the highest throne, the heir of the impregnable rock.”

Pope St. Leo III is thus addressed: “Chief pastor of the Church, fill the place of Jesus Christ.”

What must be the feelings of any sacerdotally sensitive member of the enslaved “Orthodox” clergy, when he hears his Liturgy teaching how a Pope ought to speak to a wicked or heretical sovereign! We hear Pope Gregory II warning Leo the Isaurian, the imperial champion of the Iconoclasts: “Endowed as we are with the power and sovereignty of St. Peter, we have determined to prohibit you,” etc.

Nor does this same Liturgy of the Russian Church hesitate to admit that a Roman Pontiff can excommunicate emperors as well as patriarchs; and not only emperors who belong to the Roman Patriarchate, but also those of the Eastern. In a fragment of a Life of St. John Chrysostom this Liturgy tells its admirers that

“Pope Innocent wrote more than once to Arcadius, separating him and his wife, Eudoxia, from the communion of the Church, and pronouncing anathema on all who had helped in driving St. John Chrysostom from his See. He not only deprived Theophilus (patriarch of Alexandria), but he segregated him from the Church. Then Arcadius wrote to Pope Innocent, begging pardon most humbly, and assuring the Pope of his repentance. The emperor wrote also to his brother Honorius, asking him to implore the Pontiff to lift the excommunication, and he obtained the favor.”

Protestant-tier calumnies of the ‘Orthodox’ against the papacy

It certainly appears strange that during so many centuries the leaders of the “Orthodox” Russian Church have not found some means of disembarrassing themselves of these and many similar testimonies of their own Liturgy to the supremacy of the Chair of Peter; but at least they have endeavored to neutralize the force of these arguments by a free use of that favorite weapon of all heretics—calumny.

Prince Nicholas Galitzin, writing while he was still an “Orthodox” professor, averred that “in Russian seminaries it is taught that in the eyes of Catholics the Pope is an irresponsible autocrat, claiming to be impeccable.”33

And that medical theologian, Karatheodori, whose work, by the way, was translated into French by a Russian priest formally commissioned to the task by the Russian government, dared to emit the following:

“Popery asks us to recognize in this mortal (the Pope) all the rights and all the authority of the Universal Church and what is more, it asks us to believe that by ordinance of God this mortal is superior to all the Divine Commandments themselves, and that he enjoys the right to change them, adding to them or subtracting from them according to his own will.”

‘Orthodox’ re-writing the history of the Council of Florence

Having read this barefaced illustration of “Orthodox” mendacity, we are prepared for the Greek physician’s assertion that men of the stamp of “the Jesuit Prince” (Gagarin, whose writings Karatheodori affected to refute) are “ever ready to reject the clearest truths,” and that they prosecute their ends by means of lies and the falsification of documents, following the example of the “Council of Florence, in which Cardinal Julian (Cesarini) adduced forged Acts of the Seventh General Council.”

Here the Sultan’s physician simply imitated the time-serving Mark of Ephesus in his too successful efforts to undo the good work of the Florentine synodals, carefully refraining, however, from any mention of the refutation of the Ephesine prelate’s charges which Bessarion, the most eminent Greek Schismatic of any day, and who was converted by his experience at this same Council of Florence, adduced in his apposite letter to Alexis Lascaris.

The reader will scarcely accuse us of digression, if we dilate somewhat on this charge against the Florentine synodals, since the words of Bessarion illustrate the position assumed by Karatheodori and others of that ilk.

Mark of Ephesus had accused the Latins of having adduced falsified testimonies of the Fathers as corroboratory of the Catholic doctrine on the Procession of the Holy Ghost; and to this calumny Bessarion, who was still the Schismatic Archbishop of Nicea, thus replied:

“Finally they (the Latins) showed us testimonies of the Fathers which evinced most clearly the truth of their teaching; and they adduced passages not only of Western Fathers, against which we could only contend that they had been corrupted by the Latins, but also sayings of our Epiphanius which declared plainly that the Holy Ghost proceeds from the Father and the Son, and to this evidence we also retorted that it had been corrupted.

“Then they introduced Cyprian and others, and we gave the same answer; finally we repeated this reply when they adduced the authority of Western saints.

“And when we (the Schismatics) had debated among ourselves for many days as to what we ought to say, we could devise no other reply, even though it seemed too trivial for our purpose.

“And firstly, the doctrine (of the Roman Church) appeared to be concordant with the mind of the saints; secondly, so many and so ancient were the volumes containing it, that they could not have been falsified easily, and we could show neither Latin nor Greek copies which gave the quoted passages differently from the version of the Latins; and thirdly, we were unable to cite any doctors who contradicted the Roman doctrine.

“Therefore it was that being unable to find an apposite reply, we remained silent for many days, holding no sessions with the Latins.”34

Conclusion—Why we will not be entering into the ‘Orthodox’ schism

So much for the “Orthodox” allegation of dishonesty on the part of that Ecumenical Council which put a temporary end to the Greek Schism. Such charges form the stock in trade for such of the “Orthodox” clergy as enjoy some smattering of theological education; but unfortunately for the prospects of conversion of the majority of the teachers of “Orthodoxy,” the average Protestant preacher in these United States is scarcely less versed in the essential elements of ecclesiastical lore.

Were the “Orthodox” clergy well indoctrinated even with profane science, of course not with the German materialism which alone has affected some of them, they would come to realize the truth of those words which Lamoricière addressed to the Pontifical army on the eve of the unsuccessful but glorious campaign of Castelfidardo:

“Christianity is not only the religion of the civilized world. It is the moving principle and the very life of civilization, and the Papacy is the key-stone in the arch of Christianity. To-day all Christian nations seem to have some consciousness of these truths.”

Gagarin would discern Russia among the nations whose perspicacity appealed to Lamoricière.

“Russia does not yet believe,” reflected the zealous ex-Orthodox polemic, “that the Papacy is the key-stone of Christianity; she does not comprehend the phrase, but already she seems to have a sort of consciousness of its truth, and in her pale there is an increasing number of souls who are penetrated by that truth, and who place their chief hopes in it.”35

Yonkers, N. Y.

REUBEN PARSONS.

HELP KEEP THE WM REVIEW ONLINE!

As we expand The WM Review we would like to keep providing free articles for everyone.

Our work takes a lot of time and effort to produce. If you have benefitted from it please do consider supporting us financially.

A subscription from you helps ensure that we can keep writing and sharing free material for all. Plus, you will get access to our exclusive members-only material.

(We make our members-only material freely available to clergy, priests and seminarians upon request. Please subscribe and reply to the email if this applies to you.)

Subscribe now to make sure you always receive our material. Thank you!

Further Reading

Follow on Twitter, YouTube and Telegram:

This genius probably had for his Gamaliel that theologist of Agnosticism, James Anthony Froude, who discovered that when Pope Pius IX proclaimed the dogma of the Immaculate Conception, “by one stroke of his pen he made St. Ann a virgin.”

On December 27, 1773, O. S. (January 7, 1774), Catharine wrote to Voltaire, who had alluded to his impression that the “Orthodox” rebaptized their converts from other Christian denominations: “As head of the Russian Church I cannot allow you to persist in this mistake. We do not rebaptize.”

See the American Catholic Quarterly Review, Vol. XXIII., p. 194 et seqq.

William Palmer, one of the luminaries of the Oxford Movement, characterized by Dean Church as “a man of exact and scholastic mind, well equipped at all points in controversial theology,” was perhaps most famous for his attempt to effect a union between the Russian and the Anglican Establishments. His efforts resulted only in his being told by the GrecoSlavonic heretics that he should be reconciled with his own patriarch, ere he extended the olive-branch to the separatist patriarchates of the Orient. He became a Catholic in 1856.

See Palmer’s “Eastern Question,” p. 10.

The text of the Canon is thus given in the “Juris Ecclesiastici Græcorum Historia et Monumenta, Jussu Pii. IX., P. M., Curante J. B. Pitra, S. R. E. Card.” Tom. I., p. 592:

Ἐπὶ δὲ τοῦ καταλειφθέντος ἀνδρὸς ὑπὸ τῆς γυναικός, τὴν αἰτίαν χρὴ σκοπεῖν τῆς ἐγκαταλείψεως· κἂν φανῆ ἀλόγως ἀναχωρήσασα, ὁ μὲν συγγνώμης ἐστὶν ἄξιος, ἡ δὲ ἐπιτιμίου ἡ δὲ συγγνώμη τουτῶ πρὸς τὸ κοινωνεῖν τῆ ἐκκλησία δοθήσεται.

The following is a free but accurate translation:

“If a man has been abandoned by his wife, the reason for the abandonment must be investigated; and if there seems to have been no just reason, the husband will deserve indulgence, while the wife will merit punishment the indulgence toward the husband consisting in his not being segregated from the communion of the Church.”

The judicious Oratorian, Lescœur, in his valuable work entitled “The Church in Poland” (Paris, 1876), tells us that he compared the Greek text with the Slavonic of the Kniga Pravil, or Book of Canons of the Russian Church, and with the Kormtchaia Kniga used by the Holy Synod in 1820: and that he found the three versions agreed.

For details concerning the matter of imperial interference in matrimonial causes in the days of the Eastern Empire, the reader may profitably consult Perrone’s “De Matrimonio Christiano,” Vol. III., p. 397, et seqq. Rome, 1858.

Lescœur: “L’Église et La Pologne,” Vol. II., p. 504.

Gagarin: “L’Église Russe et L’Immaculée Conception.” Paris, 1876.

In his commentary on “Le Reglement Ecclesiastique de Pierre le Grand,” p. 248.

“Le Raskol, Essai sur les Sectes Religieuses en Russie,” p. 236. Paris, 1859.

Loc. cit., Vol. II., p. 468.

“Dissertatio Historico-Ecclesiastica de Religione Ruthenorum Hodierna.” 1745.

For more information on this subject, see the already cited work of Tondini, Gagarin’s “Etudes de Theologie et d’Histoire,” Vol. I., p. 56, and De Maistre’s ‘Quatre Chapitres Inédits sur la Russie,” ch. 3. Paris, 1859.

See Gagarin’s “Clergé Russe,” p. 135.1

The reader need not be surprised at this treatment of the seminarians by the Holy Synod; for during many centuries the Russian Church has not known the meaning of the phrase “ecclesiastical vocation.” In Russia the priesthood has been, until very recently, as much a hereditary caste as it is in Hindustan; but with this difference, observes Lescœur, that in the latter country the priesthood is honored, whereas in the former to be called a son of a pope is to receive a mortal affront. See Gagarin’s “Clergé Russe,” p. 20.

Letter of July 6, 1771.

‘Études d’Histoire et de Theologie,” Vol. III., p. 483.

Some very interesting studies on the Raskolniks were published in 1874 by Leroy Beaulieu in the Revue des Deux Mondes.

“La Vérité sur la Russie,” par le Prince Pierre Dolgoroukow, p. 317. Paris, 1860.

Only three bishops sit in the Synod ex officio—those of Moscow, Kiev and St. Petersburg, and of course these can be removed from their sees at the imperial pleasure.

“De Vol. XXV.—Sig. 5 Imaginibus,” Art. II., No. 12; cited by Pope Gregory XVI. in his Brief to Mgr. Lewicki, Archbishop of Leopolis, Ruthenian Rite, July 17, 1841.

“Hist. Arian. ad Monachos,” No. 52.

What one of these pious monarchs had three “wives” at the same time? Peter had discarded Eudoxia Lapoukine as well as her successor, and was at this time, while both of these women were still living, married” to Catharine (afterward Empress as Catharine I), the wife of a Swedish soldier who had been made prisoner of war. Catharine had been the mistress of two Russian nobles before Peter “married” her.

The journals of Russia seem to consider the enslavement of both the Holy Synod and its subjects as a matter of course. On February 2, 1860, just after the death of Colonel Protasoff, the late procurator of the Synod, the Nord of St. Petersburg said:

“He was in reality, if not in name, the head of the Orthodox Church in Russia. With his firm and energetic will he knew how to conquer the retrograde tendencies of the older clergy. By means of the Synod of which he was the veritable head, he distributed mitres among young and civilized ecclesiastics,” etc., etc.

In a previous number of the QUARTERLY we have shown how Dimitri Tolstoy, although a mere civilian, was a fit successor of this colonel in the matter of civilizing the Russian clergy.

“L’Église Greco-Russe.” Paris, 1851. This Galitzin should not be confounded with another Galitzin, also a convert, and the author of “La Russie, Est Elle Schismatique ?” Paris, 1859. The name of the latter was Nicholas Borrissowitch.

For a concise but de tailed account of the beginnings of the Greek Schism, and therefore of the sufferings of Ignatius, see our “Studies in Church History,” Vol. II.

About the year 945 Olga or Elga, widow of a grand duke of Russia, journeyed to Constantinople, and was there baptized. Returning to Russia, she tried in vain to convert her countrymen. But her grandson, Vladimir, having married Anna, a sister of the Greek Emperor, Basil II., was baptized in 968, and in a few years nearly all the Russians received the faith.

See the Bollandists, at Month of September, No. 41.

Some authors hold that the Schism of Cerularius did not affect the entire Greek Empire in the eleventh century. It is certain that Pope Alexander II had an agent, an apocrisiarius (not a legate) at the court of the Emperor, Michael Ducas, in the person of Peter, Bishop of Anagni: and it is equally certain that this representative of the Papacy remained as such in Constantinople for a year.

Pope Pascal II sent Chrysolanus as legate to Alexis Comnenus. It is to be noted that Euthymius Zagabenus, who obeyed the order of Alexis Comnenus to collect all patristic testimonies against each and every heresy, never speaks of the Latins as heretics.

Even in the twelfth century there were many Greeks in the communion of Rome, as we learn from many narratives of the Crusades, from the “Alexias” of Anna Comnena, from the “Life of Mannuel,” by Nicetas Choniates, and from the letters of the Venerable Peter of Cluny to the Emperor, John Comnenus, and to the Patriarch of Constantinople.

Protestants should note this fact as evidence of their mistake when they adduce the example of the Russian Church as an encouragement for their own use of the vernacular in their Liturgy—when they have one. Not one of the ancient Churches, neither the Greeks, nor the Syrians, nor the Copts, nor the Chaldeans, nor the Armenians, nor the Nestorians, nor the Jacobites have the vernacular of the people for the medium of their Liturgy. The reason is evident; they all have preserved the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass, and they realize the necessity of having an unchangeable medium for the expression of their sentiments and doctrines—a medium which is furnished by the now unspoken languages in which their ancestors learned the truths of Christianity. For information on this point consult Assemani’s” Bibliotheca Orientalis,” Vol. IV., ch. 7, 22. Rome, 1719.

Gagarin cites the quotations which we give, and many similar ones, in the Old Slavonic text, in his “Études de Theologie,” Vol. II.; and Tondini comments on them most judiciously in his “La Primauté de Saint Pierre Prouvée par les Titres que Lui Donne L’Église Russe dans Sa Liturgie.” Paris, 1867.

“La Russie, Est-Elle Schismatique?” p. 38.

But Bessarion was not satisfied with repelling the Schismatical charge that the Roman theologians were falsifiers; he retorted the charge against the Greeks. Speaking of a passage from St. Basil in which that Father says that “the Holy Ghost is from the Son, having His being from Him, receiving from Him, and depending entirely from that Cause,” the Archbishop of Nicea declared that out of six codices of St. Basil's works brought by his fellow schismatics to Florence, five gave the passage in question in its entirety, while the sixth codex “was defective in some parts, and presented many additions which had been made according to the whims of the transcriber.”

When he returned to Constantinople, the Archbishop searched the libraries, and he discovered indeed some codices in which the questioned passage was absent ; but those codices were perfectly new, having evidently been written after the termination of the Council of Florence. At the same time the prelate found in the libraries many ancient manuscripts of St. Basil's works in which the passage occurred.

Tendances Catholiques dans La Société Russe, » Paris, 1860