Bishop Robert Barron calls Catholics to 'fight hard' against 'any' state religion, affirms condemned errors

By compromising on Catholic doctrine on the relationship between Church and State, Bishop Robert Barron can please neither Catholics nor liberals. Better to please God, regardless of the consequences.

By compromising on Catholic doctrine on the relationship between Church and State, Bishop Robert Barron can please neither Catholics nor liberals. Better to please God, regardless of the consequences.

(WM Round-Up) – Bishop Robert Barron has reaffirmed his support for the modern doctrine of religious liberty—rejected by the popes for centuries—and gone further, calling on Catholics to “fight hard” against the establishment of any “official American religion” in law.

(NB: We reported on related comments from Leo XIV yesterday—see here for more)

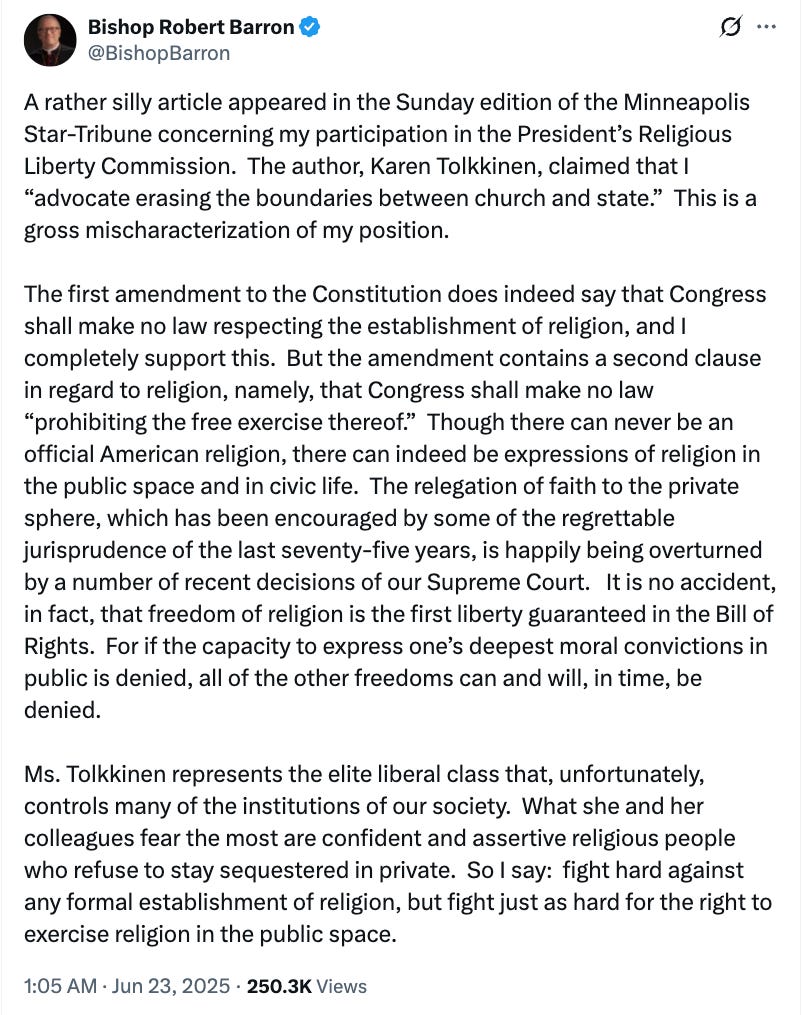

His remarks came in a June 23 tweet responding to a Minneapolis Star-Tribune article that criticised his participation in the U.S. President’s Religious Liberty Commission.

The article alleged that Barron was “erasing the boundaries between church and state.” He called the claim “a gross mischaracterization,” before restating his position.

“The first amendment to the Constitution does indeed say that Congress shall make no law respecting the establishment of religion, and I completely support this,” Barron wrote. “There can never be an official American religion.”

“Fight hard against any formal establishment of religion,” he continued, “but fight just as hard for the right to exercise religion in the public space.”

He also emphasised that “freedom of religion” is, in his view, the foundational liberty on which all others depend.

However, the Church has repeatedly and explicitly rejected these claims.

The Church’s teaching on her relationship with civil society

Barron’s framing of his stance as a defence of “religion in public life” deepens the confusion. The issue is not whether religion may appear in civic discourse, but whether states have duties toward the true religion, and what these duties are.

The idea that religious liberty is a natural right—and that governments should remain neutral towards religion—was condemned by numerous popes, including Pius IX, Leo XIII, and St Pius X.

In Quanta Cura, Pius IX condemned the following as a “totally false idea”:

... the best condition of human society is that wherein no duty is recognized by the Government of correcting, by enacted penalties, the violators of the Catholic Religion, except when the maintenance of the public peace requires it.

He condemned a similar error in n. 77 of the Syllabus of Errors.

In the present day it is no longer expedient that the Catholic religion should be held as the only religion of the State, to the exclusion of all other forms of worship. — Allocution “Nemo vestrum,” July 26, 1855.

He added that this “totally false idea” is the basis of the condemned notion of religious liberty:

From which totally false idea of social government they do not fear to foster that erroneous opinion, most fatal in its effects on the Catholic Church and the salvation of souls, called by Our Predecessor, Gregory XVI, an “insanity,” viz., that “liberty of conscience and worship is each man’s personal right, which ought to be legally proclaimed and asserted in every rightly constituted society; and that a right resides in the citizens to an absolute liberty, which should be restrained by no authority whether ecclesiastical or civil, whereby they may be able openly and publicly to manifest and declare any of their ideas whatever, either by word of mouth, by the press, or in any other way.”

This was also a condemned error included in the Syllabus of Errors:

Every man is free to embrace and profess that religion which, guided by the light of reason, he shall consider true. — Allocution “Maxima quidem,” June 9, 1862; Damnatio “Multiplices inter,” June 10, 1851.

In spite of this, Barron claims that all freedoms depend on religious liberty and liberty of expression. This directly contradicts Leo XIII’s warning that such liberty leads to “the abject submission of the soul to sin,” and implies that the Church opposed true freedom for centuries—an unacceptable suggestion.

The Church does allow limited toleration of false religions for the sake of the common good—but never recognises a right to adhere to error, let alone as the foundation of all other freedoms.

However, Pius IX also warned that a society which grants such a “liberty of perdition” in principle, and refuses to establish the religion of Christ by law…

… can have, in truth, no other end than the purpose of obtaining and amassing wealth, and that (society under such circumstances) follows no other law in its actions, except the unchastened desire of ministering to its own pleasure and interests.

Returning to the establishment of the Church by law, Pope Leo XIII wrote in Libertas that “Justice… forbids the State to be godless,” and condemned the idea that all religions should receive equal treatment. Aside from God’s own rights, this is also because man is ordered towards a supernatural destiny in Heaven, which is part of the common good which the state has a duty to safeguard:

For public authority exists for the welfare of those whom it governs; and, although its proximate end is to lead men to the prosperity found in this life, yet, in so doing, it ought not to diminish, but rather to increase, man’s capability of attaining to the supreme good in which his everlasting happiness consists: which never can be attained if religion be disregarded.

“The profession of one religion is necessary in the State,” he said in the same encyclical, adding in Immortale Dei that the state must worship God in accordance with the true religion:

[T]he State, constituted as it is, is clearly bound to act up to the manifold and weighty duties linking it to God, by the public profession of religion. Nature and reason, which command every individual devoutly to worship God in holiness, because we belong to Him and must return to Him, since from Him we came, bind also the civil community by a like law. […]

Since, then, no one is allowed to be remiss in the service due to God, and since the chief duty of all men is to cling to religion in both its reaching and practice—not such religion as they may have a preference for, but the religion which God enjoins, and which certain and most clear marks show to be the only one true religion—it is a public crime to act as though there were no God.

So, too, is it a sin for the State not to have care for religion as a something beyond its scope, or as of no practical benefit; or out of many forms of religion to adopt that one which chimes in with the fancy; for we are bound absolutely to worship God in that way which He has shown to be His will.

All who rule, therefore, would hold in honour the holy name of God, and one of their chief duties must be to favour religion, to protect it, to shield it under the credit and sanction of the laws, and neither to organize nor enact any measure that may compromise its safety. This is the bounden duty of rulers to the people over whom they rule.

“Bringing human society back to the discipline of the Church” was a central part of Pope St Pius X’s programme of “restoring all things in Christ,” as he wrote in his first encyclical E Supremi.

Further, the doctrine of Christ’s Kingship, expressed by Pius XI in Quas Primas, depends on recognising that “all men, whether collectively or individually, are under the dominion of Christ.” States have a “public duty of reverence and obedience to the rule of Christ,” the Pope taught.

The Church and the USA

The Popes did not teach that Christ’s dominion extend over the whole world except for the USA, or that religious liberty was a “deliramentum” (as Pope Gregory XVI taught) except for in the USA.

It is true that the Church has, in some places and in some respects, benefitted from constitutions which enshrine these alleged rights. In the Encyclical Longinqua to the American bishops in 1895, Leo XIII praised the Church in the United States, and acknowledged that this flourishing was in part due to the government’s toleration.

Nonetheless, he said that it would be “very erroneous” to use this as grounds for calling the traditional teaching into question:

[T]he Church amongst you, unopposed by the Constitution and government of your nation, fettered by no hostile legislation, protected against violence by the common laws and the impartiality of the tribunals, is free to live and act without hindrance.

Yet, though all this is true, it would be very erroneous to draw the conclusion that in America is to be sought the type of the most desirable status of the Church, or that it would be universally lawful or expedient for State and Church to be, as in America, dissevered and divorced.

The fact that Catholicity with you is in good condition, nay, is even enjoying a prosperous growth, is by all means to be attributed to the fecundity with which God has endowed His Church, in virtue of which unless men or circumstances interfere, she spontaneously expands and propagates herself; but she would bring forth more abundant fruits if, in addition to liberty, she enjoyed the favor of the laws and the patronage of the public authority.

Fr John Augustine Ryan, writing in 1922 provides further insight into how Catholics should understand the situation in the USA. Whilst acknowledging the benefits and justification for religious liberty in the USA, he adds:

But constitutions can be changed, and non-Catholic sects may decline to such a point that the political proscription of them may become feasible and expedient. What protection would they then have against a Catholic State? The latter could logically tolerate only such religious activities as were confined to the members of the dissenting group. It could not permit them to carry on general propaganda nor accord their organization certain privileges that had formerly been extended to all religious corporations, for example, exemption from taxation.

While all this is very true in logic and in theory, the event of its practical realization in any State or country is so remote in time and in probability that no practical man will let it disturb his equanimity or affect his attitude toward those who differ from him in religious faith. It is true, indeed, that some zealots and bigots will continue to attack the Church because they fear that some tive thousand years hence the United States may become overwhelmingly Catholic and may then restrict the freedom of non-Catholic denominations. Nevertheless, we cannot yield up the principles of eternal and unchangeable truth in order to avoid the enmity of such unreasonable persons. Moreover, it would be a futile policy; for they would not think us sincere.

Therefore, we shall continue to profess the true principles of the relations between Church and State, confident that the great majority of our fellow citizens will be sufficiently honorable to respect our devotion to truth, and sufficiently realistic to see that the danger of religious intolerance toward non-Catholics in the United States is so improbable and so far in the future that it should not occupy their time or attention.1

Conclusion

In light of all that we have seen in this piece, it is clear that Bishop Robert Barron’s message departs in a radical way from what Ryan calls “the true principles of the relations between Church and State,” which he also describes as “eternal and unchangeable.”

The claim that a right to religious liberty should be enshrined in the law is a denial of a very weighty body of magisterial teaching. It is utterly untenable to say such an alleged right is the basis of all other true freedoms.

The rejection of an established state religion, and the insistence that “there can never be an official American religion” are denials of the rights of Christ the King.

The idea that Catholics should not only benefit from religious liberty but actually fight against the establishment of the Catholic religion is essentially to contradict the Lord’s Prayer, and pray “May thy Kingdom not come”—at least, not in the USA.

This is not the first time Barron has defended these positions.

In a May 28 video, he responded to accusations of undermining the so-called religious freedom of non-conservative Christians. In response, Barron affirmed his adherence to Dignitatis Humanae, and described Vatican II as the “lodestar” and “touchstone” of his intellectual life.

As this latest response shows, Barron is discovering again that, while the Church’s traditional doctrine may displease many persons, compromising on it will never satisfy them either.

And this is why we, speaking to Barron as a fellow man for whom Christ shed his precious blood, repeat the call from our last piece:

“Save yourself from this perverse generation” (Acts 2.40). Stop trying to base your arguments on Vatican II and the “post-conciliar magisterium.” Leave aside the immoral use of the term “radical traditionalists.” Break out of the Robber Council’s paradigm. Join us!

HELP KEEP THE WM REVIEW ONLINE WITH WM+!

As we expand The WM Review we would like to keep providing free articles for everyone.

Our work takes a lot of time and effort to produce. If you have benefitted from it please do consider supporting us financially.

A subscription gets you access to our exclusive WM+ material, and helps ensure that we can keep writing and sharing free material for all.

(We make our WM+ material freely available to clergy, priests and seminarians upon request. Please subscribe and reply to the email if this applies to you.)

Subscribe to WM+ now to make sure you always receive our material. Thank you!

Further reading:

Follow on Twitter, YouTube and Telegram:

Fr John Augustine Ryan, The State and the Church, 1922. pp 38-9.

Thank you for also calling out Bishop Barron's shibboleth of allowing religion in the public square. The public square wasn't very friendly to Jesus.

There are certainly members of Congress in the US who have no problem in combining state and religion (albeit a false religion) when justifying their policies which not only affect the US but have ramifications possibly affecting the whole world. I'm speaking here of senator Ted Cruz who based on a false interpretation of scripture from his erroneous bible thinks that he can plunge the world into war and believe he's serving God. False religions lead not only to spiritual death but physical death when brought to bear in politics. The Catholic religion alone has the antidote to all the misfortunes that enevitably befall mankind when it is abandoned. It is the Kingship of Christ alone established and recognised on earth that can save us from the effects of these errors and the Catholic Church alone IS the kingdom of Christ on earth.