Is it valid? The proximate matter of Baptism

Holy Saturday prompts us to recall that the simple rite of Baptism can be rendered null, if those baptising choose to disregard the proper administration of the rite.

Holy Saturday prompts us to recall that the simple rite of Baptism can be rendered null, if those baptising choose to disregard the proper administration of the rite.

Preface to 2025 version

It gives us no great pleasure to share this article once again.

In the lead-up to Easter 2025, we have heard that more persons are being baptized in England and in France than ever before. While this may be good news in itself, we cannot help be concerned by the images and videos of baptisms shared – as several such supposed baptisms appear to be dubious or even invalid.

This 2021 article, updated in 2025, explains the problem and the solution.

Since this present article was first published, the topic, as well as both this article and its hated “table of defects” (below) have provoked very strong reactions.

On the one hand, Taylor Marshall made a YouTube show on the table and topic, and Bishop Donald Sanborn’s Most Holy Trinity Seminary—presumably independently—have published valuable material on the same subject confirming this article's thesis, as well as McCusker's article.

On the other hand, it has provoked a lot of scorn, abuse and insults on social media.

However, such abuse is marshalled not against us: it passes through us, and onto the Church’s traditional sacramental theology. And why? In order to defend the actions of careless modernists. While this is a travesty, we are content to accept personal insults if this material helps just one person.

Here, then, is the table in question. Much of the scorn that it has provoke has arisen from a failure to understand

The principles behind these verdicts

The weight of authorities for each verdict (which is certainly, not the authority of The WM Review—we are just reporting what the theologians say)

The implications of these authorities, their conclusions and their discipline being dismissed.

In the article below, each listed defect links to a further page of the authorities and an explanation of their reasoning.

Anyone who objects to the table, and takes it to social media without understanding all the available material, simply demonstrates his own shallowness.

Introduction: Are you certain that your baptism was valid?

“The proximate matter of Baptism is the use of the water […] in such a way that in the common estimation of men an ablution has been performed.”

Dominic Prümmer OP, 1956.

Baptism is necessary for salvation and for membership of the Church. As such, it is the easiest sacrament to administer: anyone can baptise; the form of words is simple; and the matter makes use of one of the most readily-available substances in the world.

Despite the simplicity of the sacramental rite, which must surely be the deliberate intention of Christ, careless and turbulent men have felt free to interfere with the received rite and render the sacrament invalid or doubtful.

Most Catholics take the validity of their own baptism for granted—but today, this assumption is no longer safe. We live in a time of disintegration: careless ministers, novel rites, and widespread presumption of validity have left many souls without the sacramental certainty they need.

Following a series of dramatic cases of invalid baptisms in 2020, many now understand how defects of form (the words) can render this sacrament doubtful or even null.

But there is another danger, far less discussed: defects in the matter of baptism, particularly in the “proximate matter” – the way water is applied. These defects are less widely known, but they can also render the sacrament invalid or doubtful.

Baptism is too important to leave in doubt. A Catholic has the right – and the duty – to have moral certainty (distinguished from physical certainty) about the validity of our baptism.

Why this matters

This guide will help you understand how baptism can be rendered invalid or doubtful, and what you should do if there is any cause for concern.

It explains the concept of proximate matter, outlines the common defects, and considers the theological and pastoral consequences.

Whether you are a convert, a priest, or a layman seeking clarity, this is a matter that cannot be ignored.

1. Non-Catholic baptisms

Ministers of the post-Vatican II “Conciliar/Synodal Church” commonly presume the validity of non-Catholic baptisms with minimal scrutiny. It is now generally sufficient for a convert to claim that he was baptised and produce a certificate: in our anecdotal experience, no serious investigation is made into whether the requirements for validity were fulfilled – and in the absence of any evidence, validity is presumed.

This optimistic approach marks a stark departure from traditional Catholic practice. Before Vatican II, the burden of proof lay on the minister to demonstrate the validity of a non-Catholic baptism. If there was any doubt about the matter, form, or intention – even that which arose simply from a lack of evidence of validity – the convert would be conditionally baptised. This once-common practice ensured sacramental certainty, whilst also avoiding the potential sacrilege of repeating an unrepeatable sacrament.

That older caution was wise. Many non-Catholic sects treat baptism casually or even irreverently. This author has personally witnessed a “We” baptism in a Protestant context, and on another occasion was rebuked by a Novus Ordo priest for even raising these issues with a fellow parishioner.

While defects of form are often audible and easily rectified, defects of proximate matter are less understood – and so are rarely addressed.

However, the problem may extend even further.

2. Baptisms in the ‘Conciliar/Synodal Church’

The problem is not confined to Protestant communities. It used to be the case that anyone who had been baptized by a Catholic priest, and whose baptism was recorded in the parish register, had moral certainty of the validity of their baptism.

However, within the post-conciliar structures themselves, many have been baptised in ways that may be doubtful or invalid – and yet even traditionalist groups treat baptisms putatively conferred in this milieu as unquestionably valid.

It is true that the post-conciliar rite retains the essential form and matter required for a valid baptism on paper. But in practice, many ministers deviate from the books, whether out of ignorance, haste, or innovation. Even among ministers seen as “orthodox,” it is far from guaranteed that the water was applied correctly, or that the basic requirements of the sacrament were fulfilled. As our co-editor M.J. McCusker has written elsewhere:

“As a consequence of this disintegration of Catholic teaching, practice, and discipline, it seems that many Catholics can no longer have moral certainty that they have been validly baptised simply because there is a record of a baptism in a register. There are reasonable grounds for considering that, as a result of the factors enumerated [in the article], something may have occurred to render their baptism invalid.

“Moral certainty can therefore only be attained by further investigation.”1

Without understanding the requirements of proximate matter, even the most well-intentioned Catholic is unable to assess whether his baptism was valid.

And yet this concept is almost never discussed, even in traditional circles. To understand why these concerns are real, we first need to examine what baptism requires.

What Makes a Baptism Valid?

The Church teaches that for any sacrament to be valid, three essential elements must be present:

Proper matter

Proper form

Proper intention

In baptism, the matter is water; the form is the Trinitarian formula (“I baptise thee in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost”); and the intention is to do what the Church does.

This guide focuses on the matter of baptism—particularly the proximate matter.

The remote matter is simply natural water—that is, water in the common estimation of men, unadulterated by other substances, and suitable for washing.

The proximate matter is the application of that water in the form of a washing.

The Church recognises three ways of applying water:

Immersion – The whole body is submerged and then drawn out, ensuring water flows over the person.

Sprinkling – Seldom used today, and fraught with risk. For validity, there must be enough water to flow and constitute a symbolic washing.

Infusion (Pouring) – The most common method in the Latin Church. Water must flow over either the entire body or at least its principal part—the head.

What matters in all three is not the method, but the whether the water is applied as a real or symbolic washing of the living body with flowing water.

There must be a washing

A sacrament is an outward sign of inward grace, which effects interiorly what it signifies exteriorly. In Baptism, the inward grace in the soul is achieved through the exterior sign of a visible cleansing of the body.

This is affirmed consistently in Catholic theology. One college textbook states:

“The proximate matter of baptism is the exterior washing of the body with water. As the very name [‘baptism’] of this sacrament indicates; as the effects it is supposed to symbolize declare; as the constant liturgical practice of the Church attests – the ceremonial action which constitutes this sacrament is one of washing, symbolic of the interior cleansing of the soul.”2

These are the basic requirements of proximate matter:

The water must flow in some way – otherwise it is not a washing

It must touch the living body – otherwise it is not a washing of the body. Parts of the body made up of dead keratin cells (such as hair and fingernails) are not parts of the living body.3

It must touch at least the head – for if it is not a washing of the entire body, it must at least be a washing of the noblest part in order to symbolically represents the whole person.

Any failure in these conditions constitutes a defect of proximate matter, and thus of the outward sign. But without the sign, there is no sacrament: if it is obscured, changed or destroyed, then the sacrament does not take place. and must be repeated conditionally.

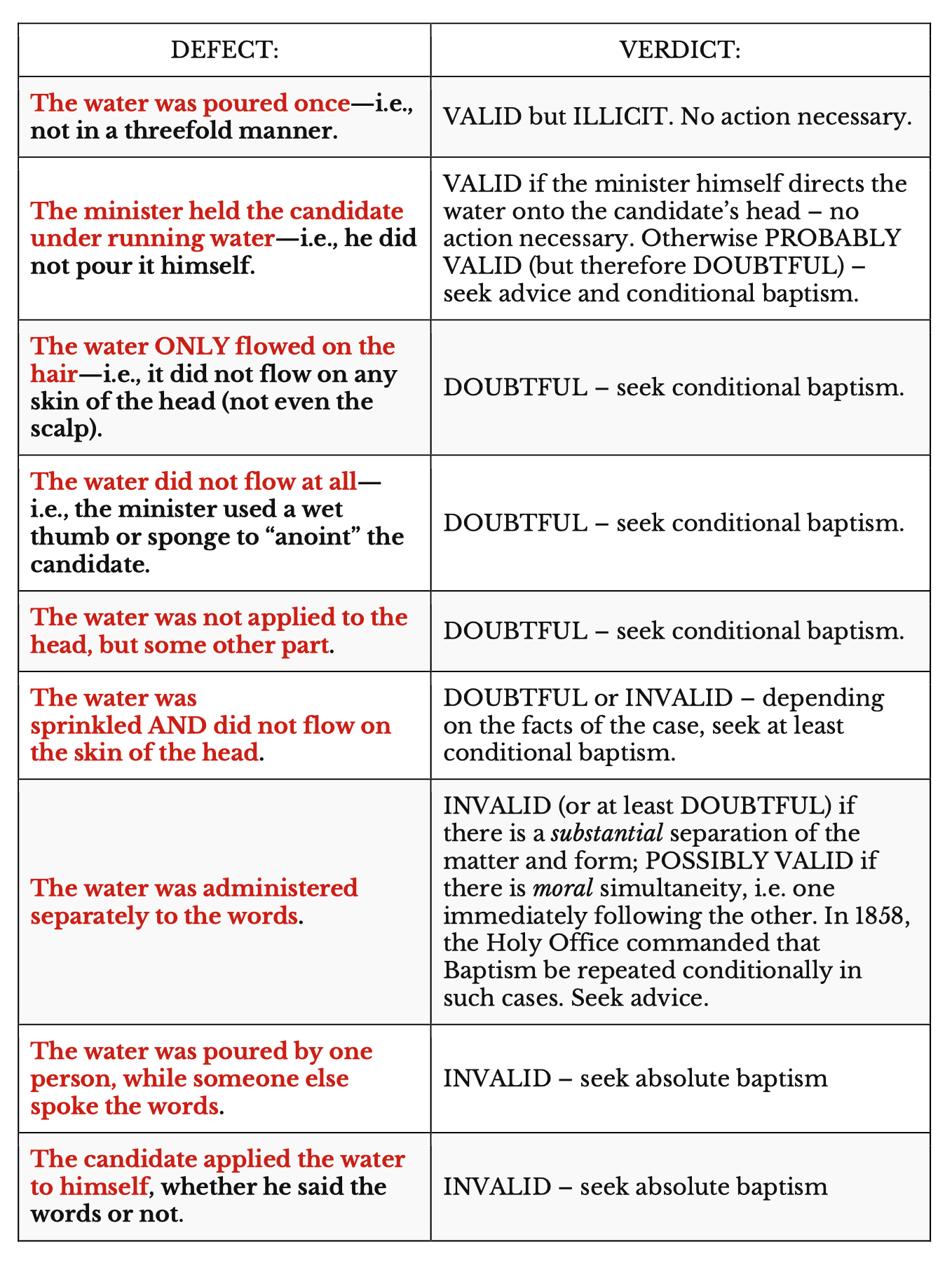

Summary of defects

Each defect below is a link—clicking on the link will take you to a series of authorities.

The water was poured once—i.e., not in a threefold manner.

VALID but ILLICIT. No action necessary.

The water was sprinkled (No link, as it is established in this present article)

VALID (if the water flowed over the skin of the head) but ILLICT.

The minister held the candidate under running water—i.e., he did not pour it himself.

VALID if the minister himself directs the water onto the candidate’s head – no action necessary. Otherwise PROBABLY VALID (but therefore DOUBTFUL) – seek advice and conditional baptism.

The water ONLY flowed on the hair—i.e., it did not flow on any skin of the head (not even the scalp).

DOUBTFUL – seek conditional baptism.

The water did not flow at all—i.e., the minister used a wet thumb or sponge to “anoint” the candidate.

DOUBTFUL – seek conditional baptism.

The water was not applied to the head, but some other part.

DOUBTFUL – seek conditional baptism.

The water was sprinkled AND did not flow on the skin of the head.

DOUBTFUL or INVALID – depending on the facts of the case, seek at least conditional baptism.

The water was administered separately to the words

INVALID (or at least DOUBTFUL) if there is a substantial separation of the matter and form; POSSIBLY VALID if there is moral simultaneity, i.e. one immediately following the other (but therefore still DOUBTFUL). In 1858, the Holy Office commanded that Baptism be repeated conditionally in such cases. Seek advice.

The water was poured by one person, while someone else spoke the words.

INVALID – seek absolute baptism

The candidate applied the water to himself, whether he said the words or not.

INVALID – seek absolute baptism

Conditional Baptism

The Church traditionally applies the principle of caution in all sacramental matters – especially baptism. When a convert presented himself for reception, the default practice was to administer conditional baptism, unless moral certainty could be established about the validity of the previous baptism. The burden of proof lay with the convert (or the priest charged with the investigation), because of the great importance of being validly baptised.

The result of all this was that that all converts enjoyed moral certainty of being truly baptised.

Since Vatican II, this practice has all but disappeared, and the burden of proof has been reversed. Converts are now expected to demonstrate why their baptism was not valid – a near-impossible task in some cases. Traditionalist groups do still maintain a practice of conditional baptism – but only for those who become Catholics under their auspices, or who were not conditionally baptised in the Novus Ordo setting. However, the rare cases of a conditional baptism in a Novus Ordo setting are usually accepted by most of these groups without question. This is an additional problem to what we have already discussed, regarding the baptisms administered in the Conciliar/Synodal milieu.

Many traditionalists presume their validity, because the rite can be valid in principle. But in practice, such baptisms are often sloppily administered. Ministers omit parts of the rite, depart from the rubrics, or fail to apply the water correctly. Worse, many have never been taught the requirements of proximate matter, or even consider such concerns to be legalistic and pharisaical.

Consider two real cases:

An adult convert known to us was once baptised by a conciliar priest using the reformed rite. The priest, now deceased, had a reputation of being a conservative. But due to the thickness of the convert’s hair, the water never touched his skin. The baptism was doubtful, but this priest’s reputation of being a conservative means that most will presume that he baptized validly.

A Protestant sect known to us administered baptism with the words: “N., we baptise you in the name of the Father, the Son and the Holy Ghost, and in the name of Jesus.” The form is invalid—not because of the final clause, but because of the use of the first-person plural.4 Were any of these individuals to present for reception today, it is unlikely that such an irregularity would even be investigated.

It is now unlikely that the average Conciliar/Synodal minister knows (or cares) about the defects to the proximate matter under discussion. The prevalence of sloppiness and innovations means that it is reasonable to be concerned that such defects may have occurred for any given baptism, unless there is some evidence to the contrary.

In short, a pattern has emerged in the Conciliar/Synodal milieu, and as such widespread access to conditional repetition of the sacraments is reasonable or even necessary.

But Would God Really Let This Happen?

Some find it hard to believe that God would allow a soul to suffer because of the fault or negligence of a minister. They ask:

Would God really withhold grace simply because a baptism was defective?

Would he “punish” someone for another man’s mistake?

Isn’t this all just theological hair-splitting?

First, let us be clear: life is full of examples of God tolerating evils, whilst drawing wonderful goods out of them.

However, these are understandable questions – but they rest on a mistaken understanding of the sacramental order, and they deserve a clear answer.

1. The question is not about damnation

First, we are not speaking here of damnation, but of the evil of an invalid or doubtful sacrament. These are very different things. Those who are damned suffer the pains of Hell on account of their own sins, and God always provides sufficient grace for each man to be saved.

However, God has also established visible, knowable means for the conferral of grace – namely, the sacraments. It is not our place to presume that he will act outside those means – especially when we ourselves have the opportunity to exercise due diligence and to remedy the situation, and yet refuse to do so out of fear or laziness.

2. The alternative destroys sacramental theology

The Church has a body of sacramental theology, taught by the magisterium, theological manuals and even in catechisms for children. As the Penny Catechism tells us, “A Sacrament is a outward sign of inward grace, ordained by Jesus Christ, by which grace is given to our souls.” If the outward sign is substantially altered or destroyed, then it is a different sign – and thus not the one ordained by Jesus Christ. We therefore have no reason to think that grace is given to our souls by means of this different sign.

This is not a legalistic rule, it is common sense. To argue that good intentions or ignorance are enough to secure the grace of baptism is to undermine this entire sacramental system. It turns the sacraments into empty gestures whose effects depend only on the subjective state of the recipient or the presumed generosity of God.

3. Not every defect renders a sacrament invalid – but some do

These points are the necessary result of the Church’s sacramental theology.

The Church’s sacramental theology does not expect perfection, or anything very difficult. It acknowledges that accidental changes may occur in the administration of the sacraments, and that these do not affect validity.

But we are not discussing such changes. We are discussing what the Church and her theologians consider to be serious and substantial defects – even if they seem small – such as separating the matter from the form, or even having one person speak the words while another administers the matter.

4. The fault lies with innovators and the negligent

Lastly, the fault lies not with the faithful, but with the innovators, the negligent, and the bishops who have failed to safeguard the sacraments. If every minister followed the infallibly safe rite handed down by the Church no concerns would arise.

The rite of baptism is completely simple to administer. In one sense, it is hard to get it wrong: the only reason it is “easy” to get it wrong is because those responsible for administering do not care about doing what the Church has told them to do.

It is precisely because they depart from the Church’s rites (even what is left of them in the Novus Ordo rites), and because discipline has broken down, that these explanations are now required.

On “legalism” and the glory of our fathers

Some may condemn all this as legalism or scrupulosity – especially if they think we are suggesting that souls may be damned through no fault of their own. But that is not what is being argued. Morality is based on reason, not fear.

However, those who criticise traditional sacramental theology as a whole must face the implications of what they are rejecting.

Those who think the points raised here are mere pedantry must produce alternative authorities, as well as an explanation of how the consistent working-out of sacramental theology could be both:

False and harmfully legalistic – and yet…

Tolerated, approved, and widely applied by Rome and the Church at large for so long a period.

In any case, the reply of Blessed Edmund Campion may well apply to those who dismiss the settled and authoritative sacramental theology of the Church as legalistic or pharisaical:

“In condemning us you condemn all your own ancestors – all the ancient priests, bishops and kings – all that was once the glory of England, the island of saints, and the most devoted child of the See of Peter.

For what have we taught, however you may qualify it with the odious name of treason, that they did not uniformly teach? To be condemned with these lights – not of England only, but of the world – by their degenerate descendants, is both gladness and glory to us.”5

What Should You Do?

The problem of doubtful or invalid baptism is more widespread than most Catholics realise – and the consequences are very serious. Without a valid baptism, one does not validly receive any other sacrament, and so any grace imparted will be determined by one’s subjective dispositions, rather than the sacrament itself.

In other words, one cannot rely on the superabundant grace which would otherwise be imparted in Holy Communion or Extreme Unction, and must rely instead on one’s own fervour.

One will not be absolved in the confessional, but must rely instead on being able to make acts of perfect contrition.

It means that one goes into the world without the sacramental grace and character of Confirmation; that one is unable to be ordained or to contract a sacramental marriage.

This is not what Christ has willed for the members of his Church: and, if moral certainty of the baptism is not attainable, it can all be resolved quickly and easily through conditional repetition of baptism.

The Church requires moral certainty to treat a sacrament as valid. If that certainty is lacking, the sacrament must be (at least conditionally) supplied. If you suspect that your baptism may have been defective – whether in form, matter, or intention – then speak to a traditional Catholic priest.

We cannot provide personal advice on such cases. This guide does not and cannot replace pastoral counsel. We are simply sharing information to assist those seeking clarity and peace of conscience.

HELP KEEP THE WM REVIEW ONLINE WITH WM+!

As we expand The WM Review we would like to keep providing free articles for everyone.

Our work takes a lot of time and effort to produce. If you have benefitted from it please do consider supporting us financially.

A subscription gets you access to our exclusive WM+ material, and helps ensure that we can keep writing and sharing free material for all.

(We make our WM+ material freely available to clergy, priests and seminarians upon request. Please subscribe and reply to the email if this applies to you.)

Subscribe to WM+ now to make sure you always receive our material. Thank you!

Further Reading:

Bishop Donald Sanborn’s study Can Novus Ordo Baptisms be Trusted as Valid? (available in a more readable format at his blog), along with…

A YouTube interview on the subject.

Summary of defects

Each defect below is a link—clicking on the link will take you to a series of authorities.

The water was poured once—i.e., not in a threefold manner.

VALID but ILLICIT. No action necessary.

The water was sprinkled (No link, as it is established in this present article)

VALID (if the water flowed over the skin of the head) but ILLICT.

The minister held the candidate under running water—i.e., he did not pour it himself.

VALID if the minister himself directs the water onto the candidate’s head – no action necessary. Otherwise PROBABLY VALID (but therefore DOUBTFUL) – seek advice and conditional baptism.

The water ONLY flowed on the hair—i.e., it did not flow on any skin of the head (not even the scalp).

DOUBTFUL – seek conditional baptism.

The water did not flow at all—i.e., the minister used a wet thumb or sponge to “anoint” the candidate.

DOUBTFUL – seek conditional baptism.

The water was not applied to the head, but some other part.

DOUBTFUL – seek conditional baptism.

The water was sprinkled AND did not flow on the skin of the head.

DOUBTFUL or INVALID – depending on the facts of the case, seek at least conditional baptism.

The water was administered separately to the words

INVALID (or at least DOUBTFUL) if there is a substantial separation of the matter and form; POSSIBLY VALID if there is moral simultaneity, i.e. one immediately following the other (but therefore still DOUBTFUL). In 1858, the Holy Office commanded that Baptism be repeated conditionally in such cases. Seek advice.

The water was poured by one person, while someone else spoke the words.

INVALID – seek absolute baptism

The candidate applied the water to himself, whether he said the words or not.

INVALID – seek absolute baptism

Follow on Twitter, YouTube and Telegram:

Donlan, Cunningham & Rock, Christ and His Sacraments, 1958. pp 335 (Reminder: we earn through this link)

Neither sacramental theologians nor scientists consider hair to be a part of the living body. While the hair follicle under the skin is living, the “hair shaft”—what we see on our heads—is made up of flat, dead cells formed from the protein keratin. Something similar applies to fingernails on humans, as well as to most horns, hooves and claws in the animal kingdom.

St Robert Bellarmine discusses “dead members” of the Church in a similar way, describing them as being of the body but without being living members.

Finally others are of the body but not of the soul, as those who have no internal virtue, but who still profess the faith and communicate in the sacraments under the rule of the pastors by reason of some temporal hope or fear. Such persons are like hairs or fingernails or diseased fluids in the human body.

This is why water that touches only the hair does not constitute a valid application of proximate matter. And when water fails to touch the skin—especially if the person has thick or dense hair—there may be no sacrament at all.

It does not seem likely that the addition of “in the name of Jesus” would cast doubt on the form. The problem lies in the use of the first person plural, as is now well known. This was witnessed by one of the editors in 2010, on one day, for several baptisms at Trinity Church (formerly Peniel Pentecostal Church), Essex.

Taken from Evelyn Waugh, Edmund Campion, Ignatius Press, San Franciscio, 2005, p 193.

All the more reason to avoid the innovators when seeking the sacraments. Avoiding also those ministers who are poorly catechised themselves and have received a less than adequate theological formation which would mean nearly all novus ordo formed ministers. This surely is a proximate matter of salvation/damnatiin otherwise the need for conditional baptism as a remedy wouldn't be necessary but merely an optional extra if one so desired. Knowing what the Church teaches concerning this sacrament and what it effects would it not be a grave error to suggest that it's necessity is relative. Even the CCC teaches that the. Church knows no other means by which a person can be incorpated into the Mystical Body of Christ absent sacramental baptism. God indeed in His mercy may have another means to sanctify the unbaptisef but this is not known by the Church.

My Anglican Baptism was 10 years ago and ill be the first one to confess my memory is not great. I know the water was only poured once so the top one definitely applies. The others, as I recall, do not.