Obedience on trial: Did St Ignatius plant the seeds of the crisis in the Church?

Dr John Lamont portrays St Ignatius and the Jesuits as largely responsible for current crises, due to 'their' conception of obedience. But the facts, theology, and history say otherwise.

Dr John Lamont portrays St Ignatius and the Jesuits as largely responsible for current crises, due to 'their' conception of obedience. But the facts, theology, and history say otherwise.

Editor’s Notes

(WM Review)—A key plank in the “narrative” for many traditionalists is as follows:

The crisis in the Church is one of obedience. Many Catholics have an exaggerated notion of obedience, leading to two problematic results:

They obey when they should not.

They draw conclusions about the nature of the crisis, and the post-conciliar claimants to the papacy, which they should not.

This narrative is crucial for the coterie of writers who have adopted for themselves the moniker of “Recognise and Resist.” The advocates of this ideology present themselves as the only ones who understand and accept the Church’s doctrine of obedience. They seem either ignorant or unwilling to admit that others also understand and accept it, but draw different conclusions.

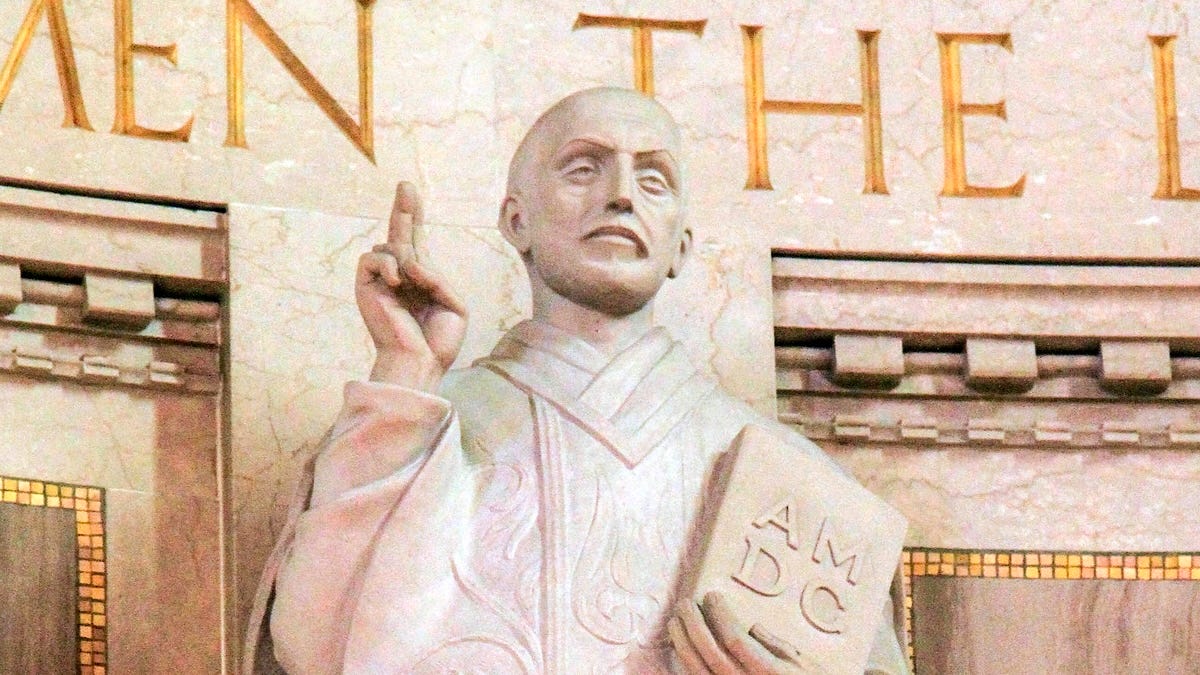

As a result this narrative—and its grave implications for the dignity and prerogatives of the Holy See—some writers amidst this coterie have begun to look further back than Vatican II or the years and decades leading to it, and have blamed the allegedly exaggerated notion of obedience on the Jesuits (the Society of Jesus)—not just in the order’s modern form, but as originally conceived by their holy founder St Ignatius of Loyola.

In recent years, this narrative has been cemented by an essay by Dr John Lamont entitled ‘Tyranny and Sexual Abuse in the Catholic Church: A Jesuit Tragedy.’ This essay is presented as an authoritative treatment by the coterie, and used as a means of advancing their ideology and its accompanying “rethinking” of the papacy.

Frankly, the temerity in such an attitude towards a saint repeatedly praised and endorsed by the Holy See—which has equally praised the Order and method of the Jesuits, which have themselves had so many evident good fruits—is unbelievable.

However, what do those “rethinking the papacy,” and using Lamont’s essay to justify it, care of the praise of the Roman Pontiffs?

What follows is Part II of a translation from a German essay by a priest who writes under the name Fr ZeloZelavi, who refutes Lamont’s essay and demonstrates that the philosophy undergirding it is liberalism.

In the previous part, Fr ZeloZelavi examined the nature of obedience as understood by the Catholic tradition, in contrast to the liberal caricature of “tyrannical authority” and “servile submission.” He demonstrated that great spiritual masters present obedience as a rational, voluntary, and virtuous act, one that elevates rather than degrades human freedom.

In this second part, ZeloZelavi turns to a specific historical accusation: the Jesuit practice of manifestatio conscientiae—the disclosure of conscience to one’s religious superior. Lamont treats this as a sign of “totalitarian control,” and alleges it played a central role in forming a tyrannical conception of authority within the Church. But is this so, or part of a broader liberal mythology around power, submission and abuse?

He also discusses Lamont’s mistreatment of St Thomas Aquinas, and demonstrates that the roots of the modern crisis do not lie in “servile obedience” but in liberalism.

Tyrannical Authority and Servile Obedience

Fr ZeloZelavi

17 January 2019

Manifestation of Conscience

16. Our learned Doctor’s accusations against St Ignatius and his Jesuits continue:

“The Jesuit approach to the manifestation of conscience contributed to inculcating a totalitarian understanding of authority.”

St Ignatius not only encouraged the manifestation of conscience but even required it, the Doctor informs us, and he required that it be made to the religious superior.

“The manifestation of conscience included ‘the dispositions and desires for the performance of good, the obstacles and difficulties encountered, the passions and temptation which move or harass the soul, the faults, that are more frequently committed … the usual pattern of conduct, affections, inclinations, propensities, temptations, and weaknesses.’”

The Saint required such a manifestation to take place every six months and issued the instruction that all superiors and even their delegates were authorised to receive it.

“Instead of restricting the purpose of the manifestation of conscience to the spiritual well-being of the manifestee, he not only permitted but required the superior to use the knowledge of his subordinates gained through the manifestation of conscience for the purposes of government.”

What a scandal!

“The overweening power that this practice gives to the religious superior needs no underlining,” the author protests indignantly. The older religious orders had resisted the introduction of such a compulsory manifestation of conscience modelled on that of Saint Ignatius, but many “modern religious institutes” had adopted it.

The abuse of this practice had been so grave, he claims, that the Pope had to intervene and prohibit it. “It was banned for all religious by canon 530 of the 1917 Code of Canon Law,” the Doctor says with satisfaction—though he must honestly add in parentheses: “The Jesuits, however, were permitted to preserve it by a special decree of Pope Pius XI.”

“By this time, however, the practice had had several centuries to leave its mark on the understanding of authority, the forms of behaviour, and the psychology of superiors and subordinates within the Catholic Church.”

17. It is true that the Church has always carefully distinguished between the forum internum (the domain of conscience) and the forum externum (the external domain), and has not desired any mixing of the two. The domain of conscience is the innermost sphere in which God and the soul meet, and into which no other has the right to intrude. Normally, only the confessor—who stands in the place of God—has the right and the competence to gain insight into the penitent’s domain of conscience. We must, however, consider the matter in greater depth to understand how the Church regards it. In the textbook of canon law by Eichmann-Mörsdorf, we read:

“The manifestation of conscience (conscientiae manifestatio) before the superior, forbidden by Leo XIII for male lay and female congregations, is now generally abrogated as an obligation for all monastic communities. No compulsion to disclose one’s conscience may be exercised. Voluntary confidential conversation is permitted; in cases of doubt and unrest of conscience, religious are even advised to open themselves to priestly (not lay) superiors (c. 530). Under no circumstances is it permitted for superiors to extort a confession of sins from their subordinates”

(Eichmann-Mörsdorf, Vol. I, Paderborn 1951, p. 468).

From this, we gather that the Church does not fundamentally exclude the manifestation of conscience before the superior—in fact, she even recommends it when it is voluntary. She does, however, distinguish between priestly and lay superiors. The reason is clear: the priestly superior, by virtue of his ordination, possesses the basic authorisation and competence to hear confessions and thus, as God’s representative, to gain insight into the soul. This is not the case with a lay superior (or a superioress).

What the Church excludes is only coercion or an obligation to disclose one’s conscience. This lies in the nature of the matter, for conscience, as the innermost domain of the soul, can only be subject to the person’s own authority. Even in confession, disclosure takes place voluntarily. And yet the Church made an exception for the Society of Jesus. Why?

18. The Society of Jesus is a clerical order. Its superiors are priestly superiors. Thus the basic condition for a disclosure of conscience is fulfilled. The Society of Jesus differs fundamentally from other religious orders. It has no actual monasteries, no religious habit, no monastic vita communis [common life] with shared choral prayer and other communal exercises. Saint Ignatius desired an apostolic way of life, such as was practised by the Saviour himself and by his Apostles.

“But as the characteristic virtue of the order, Saint Ignatius especially wished to emphasise obedience—not only because of its intrinsic excellence and the example of Christ, but also for the unity, expediency, harmony, and enduring effectiveness of the work, which only obedience is capable of imparting to an apostolic order composed of such diverse elements and spread across all countries.”

(Wetzer und Welte’s Kirchenlexikon, Vol. 6, Freiburg i.Br. 1889, col. 1385)

Obedience had to take the place of everything that enclosure, monastery, communal life, etc., provided in other religious communities. That is why St Ignatius, enlightened by the Holy Ghost—as the Church has unequivocally confirmed for us (through the approbation of his Constitutions and institutions, as well as through his canonisation)—insisted on a perfect obedience that goes even a little beyond what is customary in other orders.

The Church acknowledged this by permitting his order what it forbade to others: the obligatory disclosure of conscience to the superior. This did not serve “unrestrained power” or a “totalitarian understanding” of authority, but quite simply aimed at providing the superior with the most comprehensive and even intimate knowledge possible of his subordinates—their talents, capabilities, but also their faults and weaknesses—in order to guide and deploy them all the better, for their own salvation and for the salvation of souls. Would not many cases of “abuse” have been prevented if the superiors had been better able to assess the dangers faced by their subordinates, based on intimate knowledge of their souls? That St Ignatius was right in his conception of obedience is shown by the Church’s confirmation of it, but also by the success he achieved through it. “By their fruits ye shall know them.” How many saints has the Society of Jesus produced? How immeasurably much good has it done for the Church—in pastoral work, in the education of the young, in the missions, and so on! Would all this have been possible if it had produced nothing but spineless marionettes through “totalitarian” structures? (Cf. Der heilige Ignatius und seine Jesuiten.)

Saint Thomas

19. Lamont wishes to place the conception of St Ignatius in opposition to the position of St Thomas, and to set them against each other. St Thomas Aquinas, he says, regards the command of the superior as the true object of obedience. The lowest degree of obedience according to St Ignatius—which the latter does not regard as a virtue—is, for Saint Thomas, “the only form of obedience.”

“He holds that St. Ignatius’s alleged higher forms of obedience do not fall under the virtue of obedience at all.”

As proof, he quotes a passage from the corpus of Article 5 of Question 104 in the Secunda Secundae of the Summa Theologiae of Saint Thomas:

“Seneca says (De Beneficiis iii): ‘It is wrong to suppose that slavery falls upon the whole man: for the better part of him is excepted.’ His body is subjected and assigned to his master but his soul is his own. Consequently in matters touching the internal movement of the will man is not bound to obey his fellow-man, but God alone.”

(IIa IIae q. 104 a. 5 co.)

That liberals—and with them the “traditionalists”—are incapable of reading St Thomas properly is something we already knew. Dr Lamont is no exception. We have already treated St Thomas’s doctrine on obedience (True Obedience – Part 1) and have seen that he distinguishes three kinds of obedience: one that suffices for salvation, namely to obey in all things where one is obliged; perfect obedience, which obeys in all permitted things; and false obedience, which also obeys in forbidden things (IIa IIae q. 104 a. 5). He therefore clearly recognises several forms of obedience—a lower, a higher, and a false—and thus says nothing different from St Ignatius. As the particular object of obedience, he expressly names the implicit or explicit instruction of the superior:

“[B]ecause the superior's will, however it become known, is a tacit precept, and a man's obedience seems to be all the more prompt, forasmuch as by obeying he forestalls the express command as soon as he understands his superior's will.”

(a. 2).

That again sounds very much like St Ignatius, who says that true obedience aligns one’s own thinking and judgment with that of the superior. In Article 3, the Doctor Angelicus calls obedience the most excellent of all moral virtues, because it sacrifices one’s own will and thus the highest part of man. There he cites Pope St Gregory, who says:

“[O]bedience is rightly preferred to sacrifices, because by sacrifices another's body is slain whereas by obedience we slay our own will.”

20. What then of Dr Lamont’s objection, namely that St Thomas supposedly says that interior acts cannot be the object of obedience? It is clear that a human superior cannot command interior acts as such. Yet obedience itself obliges us to interior acts. For—and in this St Thomas and St Ignatius are fully agreed—obedience does not essentially consist in merely carrying out a command externally, while perhaps inwardly resisting or even grumbling. Everyone will recognise that this would not be a virtue.

The virtue of obedience consists precisely in subordinating one’s own will to that of the superior, and therefore it necessarily requires an interior act, even when only the external act has been commanded by the superior. Every child learns in the catechism that true obedience involves following “gladly, quickly, and exactly.” One must obey “gladly”—and that requires an interior act. But this act is not demanded by the superior; it is demanded by God himself through the command of the superior. Or how else could obedience be a sacrifice pleasing to God, in which we “slay” our highest faculty—the will—if we merely perform an outward work mechanically?

“St. Thomas does not consider obedience to involve the sacrifice of one’s will as such,” asserts the Doctor, in direct contradiction to our own findings. Let us recall once more the quotation from St Gregory, which St Thomas adopts as his own:

“[B]y sacrifices another's body is slain whereas by obedience we slay our own will.”

What else can that mean but “the sacrifice of one’s will as such”? In Dr Lamont’s narrow conceptual world, such a thing is impossible, and so in his feeble interpretation of St Thomas, it is merely the sacrifice of “self-will” that is meant—“which is defined by its adherence to objectives that are contrary to our ultimate happiness.” But such self-will would be no pleasing sacrifice to God, since it is something defective. It would be a Cain-like sacrifice. No, it is our will, with its noblest aspirations, offered on the altar of obedience, that is a sacrifice pleasing to God, like the sacrifice of Abel.

21. According to Lamont, it is once again the wicked Rodríguez who asserts that it is not merely the self-will, but “the entire human faculty of will itself, that is to be sacrificed.” This, however, he claims is:

“[A] sacrifice in the sense of an abandonment and a destruction, since it involves eliminating the operation of one’s will and handing it over to the will of another human being.”

This is nonsense, for true obedience specifically requires an activity of the will. One is to conform oneself to the will of the superior voluntarily—that is, with the full engagement of one’s own will. That perfect obedience in no way diminishes or extinguishes one’s own thinking and willing is shown as well by the much-maligned Rodríguez in his treatise on obedience. There is an entire chapter devoted to this topic (No. 15), entitled:

“It is not a breach of obedience to make suggestions” (loc. cit., p. 202).

He writes therein:

“To make a proposal to one’s superior is neither a fault nor an imperfection. On the contrary, it is a work of great perfection, and it would be a fault not to make such proposals at the proper time.”

He reproduces a prescription from the Constitutions of St Ignatius:

“Just as an excessive preoccupation with the needs of the body is blameworthy, so too a proper concern for the preservation of one’s health and bodily strength for the divine service is praiseworthy and should be exercised by all.

“Consequently, when they perceive that something else is necessary in regard to their diet, clothing, living quarters, office, or occupation, and similarly of other matters, all ought to give notice of this to the superior or to the one whom he appoints.”1

Rodríguez explains:

“The principal care for what is necessary for our well-being must indeed—and in a certain sense completely—lie with our superiors. But after all, they are men and not angels. As men, they cannot know whether you might require something beyond what is ordinarily provided. Nor can they retain every detail in memory, and therefore you must assist them in this, must remind them and make proposals to them, so that they may provide accordingly.”

We can see how reasonably St Ignatius (and his excellent disciple Rodríguez) thought, and how little they were concerned with “renouncing,” “destroying,” or even “extinguishing” the operation of human reason through obedience.

22. The great Thomist Dr Lamont also claims to know that the Angelic Doctor never regarded obedience as a virtuous form of personal asceticism. He assumes that St Thomas does not consider it more virtuous to obey a distasteful command than a command one is eager to fulfil. In fact, the opposite is the case. St Thomas explicitly states that the virtue of obedience, which for the sake of God despises one’s own will, is, simply put, more praiseworthy than the other moral virtues, which for God’s sake despise other goods (a. 3). What else can that mean, if not that obedience is a “virtuous form of personal asceticism”—and indeed a particularly excellent one? In article 2 ad 3 of Quaestio 104, the Angelic Doctor writes that “[o]bedience, like every virtue requires the will to be prompt towards its proper object, but not towards that which is repugnant to it.” He continues:

“Now the proper object of obedience is a precept, and this proceeds from another's will. Wherefore obedience make a man's will prompt in fulfilling the will of another, the maker, namely, of the precept. If that which is prescribed to him is willed by him for its own sake apart from its being prescribed, as happens in agreeable matters, he tends towards it at once by his own will and seems to comply, not on account of the precept, but on account of his own will.

“But if that which is prescribed is nowise willed for its own sake, but, considered in itself, repugnant to his own will, as happens in disagreeable matters, then it is quite evident that it is not fulfilled except on account of the precept.

“Hence Gregory says (Moral. xxxv) that ‘obedience perishes or diminishes when it holds its own in agreeable matters,’ because, to wit, one’s own will seems to tend principally, not to the accomplishment of the precept, but to the fulfilment of one's own desire; but that ‘it increases in disagreeable or difficult matters,’ because there one’s own will tends to nothing beside the precept.”

St Thomas does, of course, add that this may be true outwardly, but that in the eyes of God—who sees the interior—it may at times appear otherwise, since the will can in principle be equally obedient even in pleasant things. That, however, is likely the exception, not the rule.

“A good person,” the Doctor explains, “will be glad to carry out any suitable command, since such commands further the common good.” To be sure, every good liberal always has the “common good” in mind—or what he imagines it to be—and gladly does everything which, in his view, serves it. But where is obedience in that?

“He does not consider that all good acts are motivated by obedience to God, because he considers that there are virtues the exercise of which is prior to obedience—such as faith, which religious obedience presupposes.”

Yes, the liberal stands far above such Jesuitical depths, loftily soaring amid the theological virtues, especially that of charity!

“Nor does he consider that the essence of sin consists in disobedience to God, or even that all sin involves the sin of disobedience.”

In truth, “[a]ll sin does indeed involve a disobedience to God’s commands, but this disobedience,” says Lamont, “is not willed by the sinner unless the sin involves a will to disobey the command in addition to a will to do the forbidden act.” With this last point the Doctor again appeals to the Master of the School. However, we have not found the Article 7 of Quaestio 104 which he cites—our edition of that Quaestio contains only six articles. In the following Quaestio 105, article 1 ad 1, however, we do find the following:

“Nor again is every mortal sin disobedience, properly and essentially, but only when one contemns a precept since moral acts take their species from the end. And when a thing is done contrary to a precept, not in contempt of the precept, but with some other purpose, it is not a sin of disobedience except materially, and belongs formally to another species of sin.”

Well then, that is clear enough—but what does it contribute to our discussion?

23. The Doctor is aiming at the following point:

“Obedience is simply an act of the virtue of justice, which is motivated by love of God in the case of divine commands and love of neighbour in the case of commands of a human superior.”

How he arrives at this peculiar distinction is a mystery. As is well known, love of God and love of neighbour are one and the same divine virtue, and true obedience always proceeds from this same love, whether it concerns a divine command or a human command derived from it. But let us continue with our Doctor:

“These loves are both more fundamental and broader than obedience.”

“Faith is greater than obedience! Love is greater than obedience! Love, love above all!”—the typical creed of a liberal.

We have already pointed out on several occasions that faith is essentially obedience: we hear what God says, and we listen to what God says—that is, we obey what God says. And the divine virtue of charity is likewise not to be had without obedience, as Saint Thomas explains in Article 3 of the Quaestio in question (cf. again Der wahre Gehorsam (True Obedience)—Part 1). Certainly, faith and charity are greater than obedience; yet they always presuppose obedience as essential and include it, and therefore provide no reason to undervalue or disdain it—but on the contrary, to esteem it highly and to practise it with great care.

24. The good Doctor, in blissful ignorance and imprisoned in his prejudices, boldly claims:

“The conception of religious authority and religious obedience that became dominant in the Church from the sixteenth century onwards was thus a fundamental innovation that departed from previous Catholic positions.”

We have seen that this is not the case; quite the contrary. But Mr Lamont continues his fantasies:

“It came to influence the Church through the training given in seminaries for diocesan priests, and the approach to discipline in religious congregations. The daily life of seminarians and religious was structured by a multitude of rules governing the minutiae of behaviour, and activities that fell outside this routine could generally be pursued only with the permission of the superior. Such permission was arbitrarily refused from time to time in order to encourage submissiveness in subordinates. Reasons for orders were not provided, and questions about the reasons for orders were not answered.”

Yes indeed, what cruelty was inflicted upon those poor seminarians and religious back then! Fortunately, “Vatican II” came along and delivered us from all that!

We do not wish to deny that there were abuses and exaggerations. But a rule to be observed by all, and overseen by the superiors, is as integral to a religious house or community as the foundation is to a building. And what would obedience be worth if every instruction first had to be explained in detail and made fully intelligible? Just picture an officer on the battlefield who first has to painstakingly explain to each individual soldier why he has now issued this or that command. By the time even the last man has received a satisfactory explanation—and the matter has perhaps been debated at length—the battle is already lost.

25. According to Mr Lamont, however, this view of authority had “damaging effects on clergy and religious.”

“The exaction of servile obedience [!] from subordinates destroyed strength of character and the capacity for independent thought.”

And a liberal is the one to tell us this! If anyone has demonstrated strength of character and capacity for independent thought over the centuries, it is precisely the Jesuits. And if anything destroys strength of character and independent thought, it is liberalism—as the Doctor himself proves. But he continues to spin out his liberal fantasies:

“Exercise of tyrannical authority [!] by superiors produced overweening pride and incapacity for self-criticism. The fact that superiors all started off in a subordinate position meant that advancement was facilitated for those proficient in the arts of the slave—flattery, dissimulation, and manipulation.”

A charming, cheap cliché he offers us here. In truth, all he is doing is projecting the image of a liberal society onto the Church.

He further claims that the laity, unable to pursue a career within the ecclesiastical hierarchy, were “infantilised” in the religious sphere through a “servile understanding of religious obedience” (!). This, he says, can be observed in religious art and piety, especially from the 19th century onwards, and in the thoughtless readiness to obey the clergy.

“The resulting dissociation between adult maturity and religious belief undermined religious faith and commitment among the laity, and contributed to the steady secularization of Catholic societies.”

There we have it! Not liberalism, which spread throughout all formerly Catholic societies in the 19th century, but false Jesuit obedience is to blame for everything! One might then ask why liberals and Freemasons so hated and fought the Jesuits—when, by his account, they were so useful to their goals.

26. In the Doctor’s imagination, countermeasures were then introduced, consisting in the establishment of detailed rules in canon law, liturgy, and religious constitutions, which “limited the tyrannical exercise of authority [!] by superiors.”

“As long as the tyrannical conception of authority was restrained by these factors, it was crippling but not fatal to the Church.”

“Insidiously,” this conception of authority even appeared successful, the author admits. It put an end to the financial and sexual misconduct of the clergy, which had given impetus to the Reformation, and thus contributed to the brilliant achievements of the Counter-Reformation. Well then! one is tempted to exclaim. There we have it! “By their fruits you shall know them.” But not so for the Doctor!

With great clairvoyance he sees through the “insidious” façade and declares:

“The situation of the Church was like that of Rome under Augustus or France under Louis XIV; the peace and order produced by absolute rule permitted a flowering of the talents produced by the free society that had existed prior to absolutism. When the inheritance of freedom was spent and the full effects of absolutism were felt, these talents withered. The brilliant constellation of saints and geniuses that illuminated 17th century Catholic France was succeeded in the 18th century by failure and frequent capitulation in the face of the anti-Christian attacks of the Enlightenment.”

That this might have been a late consequence of the so-called Reformation, and not of Jesuit obedience, does not occur to the good Doctor. In fact, at the beginning of the 18th century, Jansenism was widespread in France—a movement that certainly did not spring from Jesuit obedience, but had its roots in Protestantism. One of the greatest opponents of the Jansenists, incidentally, was Saint Louis-Marie Grignion de Montfort, who, apart from the Jesuits (!), found almost no support in his efforts. And if there was a “flourishing of talents,” then it was above all in and around the Jesuit Order.

Roots of the Crisis

27. In the doctor’s view, his fantasy-history of the “tyrannical conception of authority [!] in the Church” explains many aspects of the sexual abuse crisis. To resist a sexual temptation successfully, “psychological maturity” is required. Since this is attacked by “servile obedience” (!), the practice of chastity becomes very difficult. “Warped and inadequate personalities” would not be recognised in a system of “servile obedience” (!), since they often display particular submissiveness and dissimulation, and would rise within such a system of “servile obedience” (!), while men of intelligence and character would be driven out.

What strikes us most is how often the author managed to smuggle his trauma-term “servile obedience” into these few sentences. Nothing terrifies the liberal more than the word “servant,” whereas the Saviour freely “emptied himself” and “took the form of a servant” (Phil. 2:7), and the Mother of God willingly called herself “the handmaid of the Lord.” In truth, perfect obedience is a great support for chastity, as is already indicated by the indissoluble connection between these two vows in the religious state; and what means could more swiftly identify “warped and inadequate personalities” than the disclosure of conscience, so vehemently attacked by our doctor?

But Mr Lamont’s fantasies go further still. We shall not elaborate them further here. In any case, he can only interpret the frequency of “sexual abuse” as the result of the “tyranny” (!) of authority and the “infantilisation” of subordinates, both brought about by false “servile obedience” (!).

He brings up the example of a man who, as a boy, was the victim of abuse by a priest and later testified that he had been unable to make himself understood by his parents at the time, because they were so thoroughly convinced of the priest’s sanctity that they would never have believed he could have done such a thing. “This erroneous conception of holiness was not the result of the stupidity of this man’s parents,” Lamont recognises shrewdly. “It was what they had been taught by the clergy—following a tyrannical conception (!) of authority.” They had believed that being unable to imagine that a priest could do such a thing was “virtuous and a religious duty.”

28. The poor doctor is so possessed by his pathological abhorrence of the “tyrannical conception of authority” that he once again confuses everything. Reverence for the priesthood is a normal consequence of the Fourth and Second Commandments. One of the demands of the Second Commandment is this:

“We should show respect for all that is destined for the worship of God, particularly for the servants of God, for holy places and things, for religious actions and for sacred words”

(Spirago, Volkskatechismus, p. 316).

Spirago explains further:

“Christ demands reverence for the priests; for he says: ‘He that despiseth you, despiseth me’ (Luke 10:16); ‘Touch not my anointed ones’ (1 Chron. 16:22). Do you not know that the honour shown to the priest is shown to God himself? (St Chrysostom).”

All this has nothing to do with a “tyrannical conception of authority.” It is precisely for this reason that the misdeeds of priests are especially wicked and abominable—because they abuse and damage this reverence which is justly owed to them. We see today how, particularly in recent times and under the impression of such crimes, reverence for the priesthood has plummeted. The parents of the poor man in question still possessed this reverence. That should not have prevented them from listening to their child and believing him, or at least examining the matter. They were evidently blinded by the priest, whom they also knew personally.

But that is a phenomenon not limited to the ecclesiastical sphere. Authority figures such as teachers, educators, youth coaches, etc., regularly benefit from the credit of trust which parents extend to them, which is why victims of abuse always have difficulty in being heard—even in the most liberal and highly secularised circles, where there can be no suspicion of a “tyrannical conception of authority.”

29. The “chaos that engulged the Church in the 1960s and 1970s,” the author attributes “in large part to the rebellion against the tyrannical exercise of authority” that had spread within the clergy and religious life prior to the 1960s. We do not wish to deny that there was indeed “tyrannical exercise of authority” in the Church even before the 1960s. But wherever it existed, it was not the result of the Church’s doctrine on authority and obedience, but of abuse of office. It is not obedience that makes the tyrant, but a false use of authority.

The tyrant, according to Aristotle, is not distinguished from the legitimate ruler by possessing more or greater power, but by seeking his own advantage rather than the good of his subjects. Tyranny arises easily wherever men exercise power, as Saint Thomas says, and the only remedy against it is perfect virtue (Ia IIae q. 105 ad 2). True obedience, as a virtue, is thus the very opposite of tyranny.

As with almost all revolutions, Lamont laments that the revolt against tyranny did not lead to the triumph of liberty. Instead, it brought about an even worse tyranny, having done away with the checks that had previously still existed on unrestrained power. Well, that’s how it always is. Revolution does not free one from tyranny; it leads into a still greater tyranny.

The “progressive faction that seized power in the seminaries and religious orders,” the doctor continues, “had its own programme and ideology that demanded total adherence, and that justified the ruthless suppression of opposition.” We may add that the same is true of the “conservative faction,” for both “factions” are not born of the Catholic spirit, but of the liberal spirit—the spirit of revolution and tyranny.

30. It is true, says the doctor, that part of the “progressive ideology” is the claim that the Church’s traditional teaching on sexuality is false and harmful, and the effect of this principle in the present “abuse crisis” is beyond dispute. We may once again add that it is not only the “progressive ideology” which regards the Church’s traditional teaching on sexuality as a mistaken path in need of correction, but likewise the “conservative” ideology, as exemplified by one “Saint John Paul II” with his oh-so “conservative sexual morality” in his “Theology of the Body.” If Mr. Lamont therefore notes that it is an error to believe that “progressivism as such” is to blame for the debacle, then we must agree with him. “Conservatism” is equally to blame. For both are merely forms of liberalism, which is the true culprit.

“The roots of the crisis go further back, and require a reform of attitudes to law and authority in every part of the Church,” concludes Dr. Lamont’s article, and here we are entirely in agreement. Liberalism has been at work for centuries and can only be overcome by a return to the truly Catholic “attitudes to law and authority in every part of the Church”—that attitude which was exemplarily taught and lived by the holy doctors and theologians of the Church, above all Saint Ignatius and the Jesuits.

HELP KEEP THE WM REVIEW ONLINE WITH WM+!

As we expand The WM Review we would like to keep providing free articles for everyone.

Our work takes a lot of time and effort to produce. If you have benefitted from it please do consider supporting us financially.

A subscription gets you access to our exclusive WM+ material, and helps ensure that we can keep writing and sharing free material for all.

(We make our WM+ material freely available to clergy, priests and seminarians upon request. Please subscribe and reply to the email if this applies to you.)

Subscribe to WM+ now to make sure you always receive our material. Thank you!

Read Next

Follow on Twitter, YouTube and Telegram:

Dr. Lamont, please forgive me but Saint Ignatius is a Saint. The Catholic Church would not make such mistakes - a sede who was robbed of his formation, but who still wants to be Catholic

It would have been nice to have a section to clarify the process of reasoning and discernment to follow when one is strongly suspicious or certain in ecclesial matters that obedience must be suspended i.e. when it obviously contradicts divine law or is harmful to one's salvation. Archbishop Lefebvre's arrival at his position at least to me was the epitome of such a process, but without his expression of it I would have had nowhere near enough knowledge to arrive at his justification by myself.