Law and Liberty – State Overreach and the teaching of the Catholic Church

“Liberty”, taught Pope Leo XIII, is “the highest of natural endowments”—but it can also easily be misunderstood. Here's what True freedom really entails.

This article explores the Covid-19 lockdowns in light of the Catholic Church’s teaching on liberty. It was first published in Calx Mariae in September 2020. It is republished with here in a slightly edited form with permission. References to lockdown restrictions in the United Kingdom refer to regulations in force during the summer of 2020; the Church’s teaching however is perennial.

What is liberty?

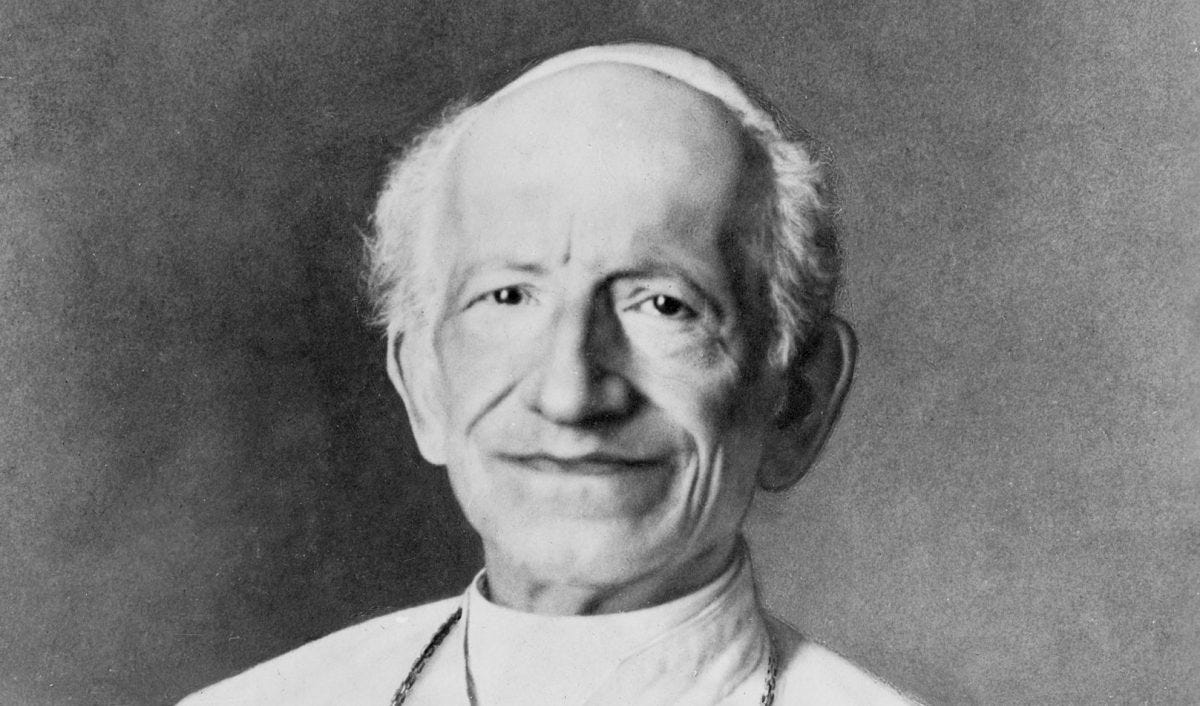

“Liberty”, taught Pope Leo XIII (pictured above) in his encyclical letter Libertas, is “the highest of natural endowments”, which “confers on man this dignity – that he is ‘in the hand of his counsel’[Eccl 15:14] and has power over his actions.”[1]

Man was created in the image and likeness of God (Gen 1:26-27) and consequently possesses the faculties of intellect and will. These confer on man “natural liberty”, the ability “of choosing means fitted for the end proposed.”[2] Man has free will, and thus is able to choose between good and evil: “on the use that is made of liberty the highest good and the greatest evil alike depend.”[3]

Pope Leo XIII taught:

“man is by nature rational. When, therefore, he acts according to reason, he acts of himself and according to his free will; and this is liberty. Whereas, when he sins, he acts in opposition to reason, is moved by another… Therefore, `whosoever committeth sin is the slave of sin.'[Jn 8:34]”

God directs man towards his proper end by a law “implanted in rational creatures, and inclining them to their right action and end”.[4] This is the “natural law” which, “is nothing but our reason, commanding us to do right and forbidding sin”.[5]

However, as Pope Leo XIII explained in his encyclical letter Immortale Dei:

“Man’s natural instinct moves him to live in civil society, for he cannot, if dwelling apart, provide himself with the necessary requirements of life, nor procure the means of developing his mental and moral faculties. Hence, it is divinely ordained that he should lead his life – be it family, or civil – with his fellow men, amongst whom alone his several wants can be adequately supplied.”[6]

But:

“as no society can hold together unless someone be over all, directing all to strive earnestly for the common good, every body politic must have a ruling authority”[7]

In order to fulfil its mission, the state has the authority to compel individuals to perform or refrain from certain acts, by means of “human laws” which must however conform to the natural and eternal law:

“the liberty of those who are in authority does not consist in the power to lay unreasonable and capricious commands upon their subjects, which would equally be criminal and would lead to the ruin of the commonwealth; but the binding force of human laws is in this, that they are to be regarded as applications of the eternal law, and incapable of sanctioning anything which is not contained in the eternal law, as in the principle of all law.”[8]

The Pope continued:

“If, then, by anyone in authority, something be sanctioned out of conformity with the principles of right reason, and consequently hurtful to the commonwealth, such an enactment can have no binding force of law, as being no rule of justice, but certain to lead men away from that good which is the very end of civil society.”[9]

Man is obliged to disobey or disregard all such invalid laws:

“But where the power to command is wanting, or where a law is enacted contrary to reason, or to the eternal law, or to some ordinance of God, obedience is unlawful, lest, while obeying man, we become disobedient to God. Thus, an effectual barrier being opposed to tyranny, the authority in the State will not have all its own way, but the interests and rights of all will be safeguarded – the rights of individuals, of domestic society, and of all the members of the commonwealth; all being free to live according to law and right reason; and in this, as We have shown, true liberty really consists.”[10]

There are certain acts that the state simply cannot command subjects to commit, or refrain from committing; whatever good end it may intend. And a government must not take actions that it knows will have damaging consequences for its citizens, unless it has well founded reasons for believing that the evil it is trying to prevent is grave enough to warrant them. Like a doctor treating a patient, the state must “first do no harm”.

These principles are of great importance when considering attempts by governments to greatly restrict the liberty of their citizens, and to forbid morally good acts (e.g. visiting family members, going out to work to provide for one’s dependents and receiving the Sacraments) in order to achieve – purportedly – another good end, in this case, the reduction in the number of lives lost to Covid-19.

Subscribe to stay in touch:

End of English liberty?

Shortly after the lockdown was imposed, a former Supreme Court judge and noted historian, Jonathan Sumption QC, set out his fears in an interview on BBC Radio 4:

“The real problem is that when human societies lose their freedom, it’s not usually because tyrants have taken it away. It’s usually because people willingly surrender their freedom in return for protection against some external threat. And the threat is usually a real threat but usually exaggerated. That’s what I fear we are seeing now.”

He continued:

“the real question is: is this serious enough to warrant putting most of our population into house imprisonment, wrecking our economy for an indefinite period, destroying businesses that honest and hardworking people have taken years to build up, saddling future generations with debt, depression, stress, heart attacks, suicides and unbelievable distress, inflicted on millions of people who are not especially vulnerable and will suffer only mild symptoms or none at all?”[11]

Lord Sumption – though he may not know it – is echoing Pope Leo XIII who warned that in a state dominated by the ideology of liberalism – such as our own – the true liberty of the individual to obey the natural and eternal law would not long survive:

“it follows that [when]… the authority in the State comes from the people only… the collective reason of the community should be the supreme guide in the management of all public affairs… With reference also to public affairs: authority is severed from the true and natural principle whence it derives all its efficacy for the common good; and the law determining what it is right to do and avoid doing is at the mercy of a majority. Now, this is simply a road leading straight to tyranny. The empire of God over man and civil society once repudiated, it follows that religion, as a public institution, can have no claim to exist, and that everything that belongs to religion will be treated with complete indifference.”[12]

In 1888 Pope Leo XIII was able to state “the powerful influence of the Church has ever been manifested in the custody and protection of the civil and political liberty of the people.”[13]

Tragically, that is no longer the case. In England and Wales, bishops not only failed to defend the “civil and political liberty of the people”, but also failed to defend the fundamental liberties of the Church.

Under the regulations in force at the time this article is written [ed. summer 2020]:

the public celebration of the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass is forbidden

the rite of baptism is explicitly forbidden

marriage before clergy, or witnesses outside one’s household, is explicitly forbidden

the administration of the sacrament of Confirmation is, in practice, forbidden

the ordination of clergy is, in practice, forbidden

leaving your home to go to confession is, in practice, forbidden.

For the first time since the Catholic Relief Act of 1791 the public practice of the Catholic faith has been suppressed. And the modern state has the power to enforce its will in a way that no previous persecuting power has possessed.

Furthermore, the regulations specifically permit churches to be used for blood donation, food banks and aid for the homeless, while forbidding their use for the public worship of the Church and the celebration of the sacraments. The government’s regulations constitute a gross insult to God. There couldn’t be a clearer demonstration of the contempt with which our political class holds the Church.

Long forgotten is the first clause of Magna Carta:

“the English Church shall be free, and shall have its rights undiminished, and its liberties unimpaired.”

The attacks on the liberty of the Church – aided and abetted by the “Catholic Bishops’ Conference of England and Wales” – are only the worst example of a whole range of measures restricting our freedoms, many of which have little or nothing to do with saving lives from Covid-19. Why, for example, did Schedule 8 of the regulations allow an individual to be committed on mental health grounds on the word of a single practitioner? And why does it increase the length of time that people can be detained on those grounds? Is the government simply using the opportunity provided by Covid-19 to increase the power of the state at the expense of the individual?

Another worrying phenomenon has been Cabinet ministers attempting to go beyond the law and impose their own opinions on the British people, using the police as a means of enforcement.

For example, the Health Secretary Matt Hancock threatened to ban people from leaving their homes for exercise, despite this being specifically permitted by the regulations. His threat was prompted by people sunbathing and sitting on park benches. Journalist Peter Hitchens pointed out that the Geneva Conventions forbid even occupying powers from engaging in collective punishment. Yet, there is a disturbing silence on the part of most of the media and political class when such statements are made.

Lord Sumption, in the interview quoted above, commented on the conduct of many of Britain’s police officers:

“the tradition of policing in this country is that policemen are citizens in uniform. They are not members of a disciplined hierarchy operating just at the government’s command. Yet in some parts of the country the police have been trying to stop people from doing things like travelling to take exercise in the open country, which are not contrary to the regulations, simply because ministers have said that they would prefer us not to. The police have no power to enforce ministers’ preferences, but only legal regulations which don’t go anything like as far as the government’s guidance…

“This is what a police state is like. It’s a state in which the government can issue orders or express preferences with no legal authority and the police will enforce ministers’ wishes… There is a natural tendency of course, and a strong temptation for the police to lose sight of their real functions and turn themselves from citizens in uniform into glorified school prefects.”

Some police forces have used social media to threaten to report parents to social services if their children are found outside the house during lockdown. In other cases, police have illegally entered private property, and in one notorious case a police officer in Lancashire threatened to “make up” false accusations unless a young man complied with his instructions.

We have also seen a further development of the disturbing trend by which the police attempt to “educate” the population. In February this year, Mr Justice Julian Knowles, when ruling against police officers who had visited a man’s workplace to speak to him about allegedly “transphobic” tweets, compared the actions of Humberside police to “a Cheka, a Gestapo or a Stasi.” And he suggested this was the behaviour of “an Orwellian society.”

George Orwell came to mind when I first read the following words from Simon Kempton, “Operational Lead for Coronavirus at the Police Federation of England and Wales”:

“there are still a minority of members of the public who simply do not wish to comply with the restrictions…

“And most of those individuals wanted to argue their case as to why they were doing something within the guidelines.

“What would help perhaps is engaging the public on an emotional level so more of them wanted to comply, not just that they felt they had to comply, but they wanted to comply.”[14]

Mr Kempton’s comments seem to express the same sentiments as the words of O’Brien in George Orwell’s 1984, spoken during the interrogation and torture of Winston Smith:

“We are not interested in those stupid crimes that you have committed. The Party is not interested in the overt act: the thought is all we care about. We do not merely destroy our enemies, we change them.”

and

“We are not content with negative obedience, nor even with the most abject submission. When you finally surrender to us, it must be of your own free will.”

In the end, they are determined that we must love Big Brother.

The English Constitution

It’s important to raise our voices in the face of such draconian assaults on our liberties, because our ancient political and legal system, with which are freedoms are inextricably connected, is in critical danger. Our ancient unwritten Constitution has developed organically over many centuries and, once severely wounded, it may be impossible to heal.

John Henry Newman’s warning, issued during the Crimean war, reminds us that actions that are intended to do good can have unintended harmful consequences:

“No one likes to use a cumbrous, clumsy instrument… it is just possible we may alter our institutions, under the immediate pressure, in order to make them work easier for the object… There are abundant symptoms, on all sides of us, of the presence of a strong temptation to some such temerarious proceeding. Any one, then, who, like myself, is thankful that he is born under the British Constitution, – any Catholic who dreads the knout and the tar-barrel, will, for that very reason, look with great jealousy on a state of things which not only doubles prices and taxes, but which may bring about a sudden infringement and an irreparable injury of that remarkable polity, which the world never saw before, or elsewhere, and which it is so pleasant to live under… it would be no consolation to me to be told that the Constitution will last my day, if I know that the next generation, whom I am watching as they come into active life, would fall under a form of government less favourable to the Church.”[15]

Many have written about the remarkable nature of the English Constitution, which Catholic political theorist Joseph de Maistre, called “the most propitious equilibrium of political powers that the world has ever seen”. The words of Newman are particularly apt:

“a Constitution really is not a mere code of laws, as is plain at once; for the very problem is how to confine power within the law, and in order to the maintenance of law. The ruling power can, and may, overturn law and law-makers, as Cromwell did, by the same sword with which he protects them. Acts of Parliament, Magna Carta, the Bill of Rights, the Reform Bill, none of these are the British Constitution. What then is conveyed in that word?”[16]

“A constitution” he continued:

“is something more than law; it is the embodiment of special ideas, ideas perhaps which have been held by a race for ages, which are of immemorial usage, which have fixed themselves in its innermost heart, which are in its eyes sacred to it, and have practically the force of eternal truths, whether they be such or not. These ideas are sometimes trivial, and, at first sight, even absurd: sometimes they are superstitious, sometimes they are great or beautiful; but to those to whom they belong they are first principles, watchwords, common property, natural ties, a cause to fight for, an occasion of self-sacrifice. They are the expressions of some or other sentiment, – of loyalty, of order, of duty, of honour, of faith, of justice, of glory. They are the creative and conservative influences of Society; they erect nations into States, and invest States with Constitutions. They inspire and sway, as well as restrain, the ruler of a people, for he himself is but one of that people to which they belong.”[17]

For our ancestors, our ancient liberties were more precious than life itself, as the war memorials in all our cities, towns and villages should daily remind us. The Englishman was jealous of his liberty and would defend it against all comers:

“…an Englishman” wrote Newman “likes to take his own matters into his own hands. He stands on his own ground… He can join too with others, and has a turn for organising, but he insists on its being voluntary. He is jealous of no one, except kings and governments, and offensive to no one except their partisans and creatures.”[18]

Now more than ever we must act to ensure that the old “watchwords” will continue to bind us together as a free people – responsible before God for the right exercise of our natural liberty – and that we resist the temptation to hand over the management of our lives to the “partisans and creatures” of the state.

How and when did this temptation to servility become so strong?

This is a very complex question and cannot be adequately addressed here. But some interesting insights into the process are offered by Hilaire Belloc’s 1911 work The Servile State, in which he posits that the society of his own day – in which a wealthy few exploited the impoverished many – could not last without profound alteration.

Three options, he argued, were open to his contemporaries:

Policies which would lead to the return of a society in which the many, not the few, controlled the means of production

A collectivist society in which the state controlled the means of production on behalf of all or

A state in which the many remained economically dependent on the few but were preserved from insecurity and poverty by the state and the elite acting together, at the cost of their political freedom.

This latter alternative he called “the servile state”. Belloc spent his life working for the first option but recognised that society was moving rapidly towards the third. The second, socialism, was, he asserted, impossible to achieve and would always lead in the end to the “servile state”.

Belloc’s book explores how people will surrender freedom in return for security. While he focuses on the insecurity caused by poverty – or the fear of it – his insights are also applicable to our current surrender of political freedom out of fear of disease.

Towards the close of the book he discusses four “characters” whose actions are responsible for society moving “towards stability by losing its essential character of political freedom”. These characters will be very recognisable to all of us.

First, there is the well-meaning politician who pursues a course of action out of misguided compassion. Out of a genuine desire to save lives he gives uncritical support to harmful measures.

The second group, “the statisticians”, are more sinister, and they are at the forefront of the present attacks on our liberty. They are those who love state power in and of itself. They long for an “ordered and regular form of society” in which power lies with “public officials who shall order other men about to preserve them from the consequences of their vice, ignorance and folly”.

Belloc writes:

“Tables, statistics, and exact framework for life – these afford him food that satisfies his moral appetite; the occupation most congenial to him is the ‘running’ of men: as a machine is run.”

At present we hear the voice of “the statistician” daily, deciding on our behalf, according to the latest statistical models, how long it will be before we have our basic liberties restored. On their models and theories all depends: whether this or that business will go under, whether this ailing grandmother will ever see her new grandchild, and when the public worship of the Church will be restored. All our lives, all our plans – even who will live and who will die – all depend on their models. This is not freedom, but “the tyranny of experts”.

The third character is “the Practical Man”, that is, he “who depends on his shortness of sight, and is therefore today a powerful factor”.

Belloc explains:

“twin disabilities… stamp the Practical Man… an inability to define his own first principles and an inability to follow the consequences proceeding from his own action.

“Both these disabilities proceed from one simple and deplorable form of impotence, the inability to think.

“…The two things intolerable to him as a decent citizen (though a very stupid human being) are insufficiency and insecurity.”

Belloc continues:

“He ‘takes the world as he finds it’ and the consequence is that whereas men of greater capacity may admit with different degrees of reluctance the general principles of the Servile State, the Practical Man, positively gloats on every new detail in the building up of that form of society. And the destruction of freedom by inches (though he does not see it to be the destruction of freedom) is the one panacea so obvious that he marvels at the doctrinaires who resist or suspect the process.

…

“It has been necessary to waste so much time on this deplorable individual because the circumstances of our generation give him a peculiar power… He is to be found as he never was in any other society before our own, possessed of wealth, and political as never was any such citizen until our time. Of history with all its lessons; of the great schemes of philosophy and religion, of human nature itself he is blank.

“The Practical Man left to himself would not produce the Servile State. He would not produce anything but a welter of anarchic restrictions which would lead at last to some kind of revolt.

“Unfortunately, he is not left to himself. He is but the ally or flanking party of great forces which he does nothing to oppose, and of particular men, able and prepared for the work of general change, who use him with gratitude and contempt.”

We see the “Practical Man” today in those who uncritically support government policy and who pour abuse and ridicule on those who dare to raise legitimate concerns. The “Practical Man” – secure in his own ignorance and pride – attributes bad motives to those who, capable of thinking for themselves, raise the alarm about the catastrophic economic impact of the lockdown and its consequences on our fundamental liberties.

Belloc’s fourth category is the ordinary people who make up the vast majority of the population.

Belloc warned that already in his own day the old English traditions and the memory of true freedom were failing, something he linked to forty years of compulsory education. And now, a century later, and after decades of deliberate indoctrination by the state and the media, very few of our contemporaries have an adequate grasp of what is taking place.

The generations that have grown up since the beginnings of the welfare state, which can be dated to the National Insurance Act 1911, and especially those born since its rapid expansion after 1945 – “the baby boomers” – have been increasingly protected from “cradle to grave” by a powerful and ever more intrusive state. The state has progressively transferred power away from individuals, families, local communities and the Church. This is in opposition to the Church’s teaching on subsidiarity which was clearly expressed by Pope Pius XI in his encyclical Quadragesima Anno:

“it is gravely wrong to take from individuals what they can accomplish by their own initiative and industry and give it to the community… also it is an injustice and at the same time a grave evil and disturbance of right order to assign to a greater and higher association what lesser and subordinate organizations can do. For every social activity ought of its very nature to furnish help to the members of the body social, and never destroy and absorb them.

“The supreme authority of the State ought, therefore, to let subordinate groups handle matters and concerns of lesser importance, which would otherwise dissipate its efforts greatly.”[19]

Our society has now reached the point where we so instinctively look to the state for direction, that we neglect our responsibility to conduct our own affairs. The modern British public has an insatiable appetite for security but, it seems, not much of an appetite for freedom.

Man was made for life, not death

Underlying this appetite for security is a deep-seated nihilism and despair, which leads to regarding natural death as the greatest of evils. In an article in First Things entitled “Say ‘No’ to death’s dominion” its editor R. R. Reno expressed this movingly:

“Everything for the sake of physical life? What about justice, beauty, and honor? There are many things more precious than life…”

He continues:

“There is a demonic side to the sentimentalism of saving lives at any cost. Satan rules a kingdom in which the ultimate power of death is announced morning, noon, and night. But Satan cannot rule directly. God alone has the power of life and death, and thus Satan can only rule indirectly. He must rely on our fear of death.”[20]

Our reaction to the Covid-19 pandemic contrasts starkly with how our grandparents and great-grandparents responded to the much more deadly Spanish flu pandemic of 1918-19. R.R Reno writes:

“Their reaction was vastly different from ours. They continued to worship, go to musical performances, clash on football fields, and gather with friends.

“We tell ourselves a fairy tale about that reaction: Those old-fashioned people were superstitious and ignorant about medical science. They abandoned the weak to the slaughter of the disease for no good reason. We, by contrast, are scientific and pro-active, meeting the threat of disease with much greater intelligence and moral rectitude. We suspend worship and postpone concerts. I’m sure we’ll cancel family reunions as well. We know best what is most important—saving lives!

“That older generation that endured the Spanish flu, now long gone, was not ill-informed. People in that era were attended by medical professionals who fully understood the spread of disease and methods of quarantine. Unlike us, however, that generation did not want to live under Satan’s rule, not even for a season. They insisted that man was made for life, not death. They bowed their head before the storm of disease and endured its punishing blows, but they otherwise stood firm and continued to work, worship, and play, insisting that fear of death would not govern their societies or their lives.

“We, by contrast, are collectively required to cower in fear—fear that we’ll die redoubled by the fear that we’ll cause others to die. We are stripped of whatever courage we might be capable of…

“Alexander Solzhenitsyn resolutely rejected the materialist principle of ‘survival at any price.’ It strips us of our humanity. This holds true for a judgment about the fate of others as much as it does for ourselves. We must reject the specious moralism that places fear of death at the center of life.”

Fear of death the foundation of the “servile state”

The fear of death is ushering in the final stages of the “servile state”, which Belloc warned in 1911:

“[is] no longer a menace but something in actual existence. It is in process of construction. The first main lines of it are already plotted out; the corner-stone of it is already laid…

“They are the admitted foundations of a new order, deliberately planned by a few, confusedly accepted by the many, as the basis upon which a novel and stable society shall arise to replace the unstable and passing phase of capitalism.”

More than a century later the process of construction is approaching its completion – it only remains for the windows to be sealed and the doors to be permanently locked.

Does any hope remain?

Belloc saw only one salvation: the West must return to the Catholic faith. Humanly speaking, this might now seem a distant hope, yet we must always remember that we have no cause for despair.

In the end My Immaculate Heart will Triumph!

HELP KEEP THE WM REVIEW ONLINE!

As we expand The WM Review we would like to keep providing free articles for everyone.

Our work takes a lot of time and effort to produce. If you have benefitted from it please do consider supporting us financially.

A subscription from you helps ensure that we can keep writing and sharing free material for all. Plus, you will get access to our exclusive members-only material.

(We make our members-only material freely available to clergy, priests and seminarians upon request. Please subscribe and reply to the email if this applies to you.)

Subscribe now to make sure you always receive our material. Thank you!

Further Reading:

Follow on Twitter, YouTube and Telegram:

[1] Pope Leo XIII, Encyclical letter Libertas, promulgated 20 June 1888, No 1.

[2] Pope Leo XIII, Libertas, No. 5

[3] Ibid.

[4] Pope Leo XIII, Libertas, No. 8.

[5] Libertas, No. 8.

[6] Pope Leo XIII, Encyclical letter Immortale Dei, No. 3.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Libertas, No. 10.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Libertas, No. 13.

[11] Jonathan Sumption, interview on The World at One, BBC Radio 4, 30 March 2020.

[12] Libertas, No.16.

[13] Libertas, No.18.

[14] “Sunbathing is banned”, The Daily Mail, 6 April 2020, [accessed online].

[15] John Henry Newman, “Who’s to Blame?”, first published in the Catholic Standard during the Crimean War and re-published in Discussions and Arguments, (London, 1872).

[16] Ibid.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Pope Pius XI, Quadragesima Anno, Nos. 79-80.

[20] R. R. Reno, “Say ‘No’ to death’s dominion”, First Things, 23 March 2020.