Did Pope St Pius X condemn Newman in Lamentabili sane?

Every now and then we are told that Newman taught a proposition condemned by Pope St Pius X in Lamentabili Sane. Fr Edmond Benard shows that this is not the case.

Every now and then we are told that Newman taught a proposition condemned by Pope St Pius X in Lamentabili Sane. Fr Edmond Benard shows that this is not the case.

Editor’s Notes

Regular readers will know that ‘The Anti-Newman Legend’ is a favourite topic of The WM Review.

In a recent livestream – the same in which The WM Review was mentioned – His Excellency Bishop Donald Sanborn made the following claim about Cardinal John Henry Newman:

“I just read the other that he said that the motives of credibility of the Catholic Faith are merely an agglomeration of many probabilities. That is actually condemned by the Church.”1

The proposition which Pope St Pius X condemned is as follows:

“The assent of faith ultimately rests on a mass of probabilities.”

“Assensus fidei ultimo innititur in congerie probabilitatum.”(Lamentabili sane exitu, n. 25)

We can see from the outset that the accusation is imprecise: Pope St Pius X was condemning a proposition that referred to the assent of faith, and not to the motives of credibility. When someone is alleging that another man’s words have been condemned by the Church, it seems reasonable to insist that he represent both the man’s words and the Church’s condemnation with precision.

The pedigree of the accusation

Although this seems to be the first time that Bishop Sanborn has made this particular accusation, it has been around for decades – indeed, over a century.

In that time, it has been the Modernists themselves who have made this claim, whereas Catholics – even those critical of Newman, such as Cardinal Lépicier – denied it.

Bishop Edward Thomas O’Dwyer of Limerick also defended Newman against this charge, in a work approved by Pope St Pius X.

It is certainly true that Newman wrote something like the condemned proposition on several occasions in his body of work. But a merely material similarity is not sufficient to condemn someone. After all, propositions which include the words homoousios and homoiousios could be very similar – and we do not condemn statements containing the former word because of its similarity with the latter.

Fr Edmond Benard’s analysis

In order to consider this topic, let us turn to Fr Edmond Benard – the author of the work A Preface to Newman’s Theology – who addressed this accusation in details (and dismissed it) 80 years ago, in 1945. He shows that Loisy and the modernists distorted Newman’s words, and did violence to the legitimate meaning which the Cardinal had originally expressed. This is why he concludes:

“Evidently anyone who takes a little trouble to ascertain Newman’s exact meaning and to view his theory as a whole, and then to compare it with the error condemned in the decree Lamentabili, would hardly fall into the mistake of gratuitously extending the condemnation of the Holy See to one whom it has never intended to encompass.”

Who was Fr Benard? He was responsible for a very helpful essay about Pius XII’s teaching on the merely authentic magisterium of the Roman Pontiff. Novus Ordo Watch has previously described him, in relation to the book on Newman, as follows:

“The author, Fr. Benard, was an incredibly gifted young priest who was just rising to prominence as a Newman scholar. He died a premature death in his study at the Catholic University of America, during a fire on Feb. 4, 1961, presumably of smoke inhalation. However, knowing all the evils that would afflict the Church and society afterwards, we can see what a great mercy of Almighty God it was to call him to judgment when He did. Fr. Benard died at the young age of 46, but he lived long enough to leave to posterity this magnificent vindication of Newman’s orthodoxy.”

A more balanced approach

Although we have published much in defence of Newman, we do not wish to take a partisan line and defend the late Cardinal at all costs.

The very next chapter in Benard's work contains a critical appraisal of the Grammar of Assent. Overall, he account of Newman’s writings is balanced, containing criticism as well as defence and praise. This is the correct, and just approach, more or less followed by Fr Marín-Sola and Cardinal Lépicier in the texts which we have published: would that Newman’s contemporary critics followed it as well.

We note that, in the livestream in question, Bishop Sanborn has appeared to take something of more of balanced approach to Newman than in the past. He emphasised his acceptance of Pope St Pius X’s letter vindicating Newman’s orthodoxy. The presenter, Stephen Heiner, also raised the possibility that someone could be a canonised saint, in spite of holding to theological errors in good faith, which the Bishop granted.2

On another recent occasion, the Bishop also said:

“Cardinal Newman made a very explicit declaration of faith, which in a way absolved him of some of his former errors, so I wouldn’t say that he was a heretic or anything like that.”3

With that established, let us turn to Fr Benard’s account of the matter.

The Grammar of Assent and the Modernists

A Preface to Newman’s Theology

Chapter XVIII

Fr Edmond D. Benard

B. Herder Book Co., London 1945.

The condemnation in Laentabili sane

On July 3, 1907, the Sacred Congregation of the Holy Office issued a decree beginning with the words Lamentabili sane exitu, and listing and condemning sixty-five propositions of the Modernists. The twenty-fifth proposition to be proscribed read:

“The assent of faith is ultimately founded on a collection of probabilities.”4

“This,” wrote Alfred Loisy flatly, “was Newman’s doctrine.” Loisy “did not wish to believe that the Sacred Congregation desired to condemn Newman,” so he advanced the theory that the proposition might have been found in the works of some of Newman’s “disciples” or in Houtin’s writings or in a late work of his own. The impression he undoubtedly wishes to convey is that the Congregation, by condemning the Modernists for holding such a doctrine, had, whether it wished to or not, condemned Newman with them.5

What was Newman’s doctrine, and was it what St Pius X condemned?

The first question to be considered in this chapter is whether Newman’s theory of probabilities as definitively outlined in the Grammar of Assent was of such a nature as to fall under the condemnation expressed in proposition twenty-five.

It will be remarked that the proposition speaks only of a collection (“congeries”) of probabilities. It does not speak of the convergence of probabilities, and we have indeed no right to stretch the condemnation to include this method of proof by convergence, a method which, so far as we know, no authoritative Catholic apologist has repudiated.6

A sufficient number of independent facts, each in itself only a probable indication, but all converging toward one explanation, one justifying reason, one solution, are a legitimate source of certitude. Why? Because there must be a reason for this convergence, and the proof is thus based, not on the fact that our multiple indications are only probable, but that their convergence toward one solution must have a reason, and that the reason can be only the truth of that solution toward which the probabilities point. Thus the probabilities coalesce to form a certain, factual premise of an implicit syllogism, the other premise being the certain principle of sufficient reason, and the conclusion thus being certain.

Newman’s method of proof from probabilities was, in effect, nothing more nor less than this. He did not maintain that certitude was based on the mere collection of probabilities, but in their unanimous convergence toward one, and only one, solution or explanation.7

Newman also (and this is a point which seems to have escaped the notice of those authors who have defended him against Loisy’s charge) clearly implies the use of the principle of sufficient reason, although naturally he brought nothing so “metaphysical” explicitly into the Grammar. Discussing the proof of revelation, he wrote:

“Here, as in Astronomy, is the same absence of demonstration of the thesis, the same cumulating and converging indications of it, the same indirectness in the proof, as being per impossibile, the same recognition nevertheless that the conclusion is not only probable but true.8

“The logical form of this argument, is, as I have already observed, indirect, viz. that ‘the conclusion cannot be otherwise,’ and Butler says that an event is proved, if its antecedents ‘could not in reason be supposed to have happened unless it were true,’ and law-books tell us that the principle of circumstantial evidence is the reductio ad absurdum.”9

The proof by converging probabilities is “indirect,” “per impossibile,” etc., simply because there must be a sufficient reason for the convergence; because such a convergence would be impossible without this reason; and because the conclusion to which the probabilities tend cannot be otherwise than as indicated by these probabilities, because there would then be no sufficient reason for their convergence upon it.

Without saying so in the exact words, Newman has thus shown that his theory clearly implies, as an integral part, the principle of sufficient reason. If the Illative Sense, as Newman holds, recognizes the certitude which is the valid result of this convergence of probabilities, we may attribute the fact to its quasi-instinctive recognition of the principle of sufficient reason as a law of being and of thought.

Evidently anyone who takes a little trouble to ascertain Newman’s exact meaning and to view his theory as a whole, and then to compare it with the error condemned in the decree Lamentabili, would hardly fall into the mistake of gratuitously extending the condemnation of the Holy See to one whom it has never intended to encompass.

Do the modernists actually even adhere to Newman’s doctrine?

The second question for consideration in this matter is whether the Modernists faithfully reproduced Newman’s doctrine. Essentially the question is already answered by the facts: had they done so, their theory about probabilities would not have been condemned. As Christian Pesch, S.J., remarks, if the Modernists had been content with maintaining, as did Newman, simply that moral certitude is often arrived at by arguments which, taken one by one, are only probable and that this is a sufficient certitude for the preambles of faith, they would have held nothing but the truth.10

To bring our discussion down to concrete details, we will let Alfred Loisy be the spokesman for the Modernist “disciples” of Newman. In maintaining that Newman was included in the condemnation contained in proposition XXV of Lamentabili, Loisy claimed to have “reproduced” Newman’s doctrine in his article of March 15, 1900, in the Revue du clergé français. He also suggested that the Sacred Congregation may have found their censurable proposition in a volume of Houtin’s which cited this article. We are, then, within our rights in using this Loisy article as an example of the way the Modernists understood and “reproduced” Newman’s theory.11

On reading the article, we are struck by a surprising circumstance. Instead of citing the work in which Newman treats his doctrine ex professo and in detail— the Grammar of Assent—the only quotation from the Cardinal which Loisy uses in the course of the entire article is a passage from the Apologia pro Vita Sua. The context in which Loisy places this citation is remarkable:

“True religion is made to be known, experienced, lived, and this intimate experience has always been its true demonstration, changeable in its logical expression according to time and even persons, certain for all who believe, that is, for those who, regarding religion closely enough to know it well in itself and in relation to themselves, have the courage to embrace it by an act of the will… The most learned demonstration changes nothing regarding these conditions essential to faith. Here is what Cardinal Newman has written:

‘I say, that I believed in God on a ground of probability, that I believed in Christianity on a probability, and that I believed in Catholicism on a probability, and that these three grounds of probability, distinct from each other of course in subject matter, were still all of them one and the same in nature of proof, as being probabilities—probabilities of a special kind, a cumulative, a transcendent probability but still probability; inasmuch as He who made us has so willed, that in mathematics indeed we should arrive at certitude by rigid demonstration, but in religious inquiry we should arrive at certitude by accumulated probabilities;—He has willed, I say, that we should so act, and, as willing it, He co-operates with us in our acting, and thereby enables us to do that which He wills us to do, and carries us on, if our will does but co-operate with His, to a certitude which rises higher than the logical force of our conclusions.’

“In other words, the demonstration is perfected in the very reality of faith, in its substantial truth, from whence glows upon the mass of probabilities the ray of light which illumines them, the life which animates them, and the unshakable certitude which binds them together. Faith, we repeat, does not cease to be profoundly reasonable, although it is not an affair of rational speculation; but its high rationability appears in its full evidence only to those who sincerely desire to know it, and who are not afraid of the truth. There is nothing, to prevent the ignorant man from succeeding after his fashion just as well as the learned, without so much research and discussion.

This understood, the certitude of revelation is not diminished; it is referred to its true character, which is to be a certitude of faith, and not a scientific certitude.12

Here, as in most of Alfred Loisy’s writings before his final break with the Church, we find a strange mixture of verbal orthodoxy side by side with the dangerously tendentious, and between the lines the suggestion of a mode of thought completely untenable for a Catholic.

How Loisy distorted Newman’s words

Loisy involves in a hopeless confusion the absolute supernatural certitude which is the concomitant result of the divinely infused virtue of faith and the natural moral certitude which can be evoked by the spectacle of the multitude of probable arguments all converging toward the proof of revelation. It is his theory that only faith gives to the probabilities their probative value in the first place; it is only after faith has come, and in its light, that he would have the believer realize the cogent power of the convergent mass of probable arguments. He follows his quotation from Newman with the sentence:

“In other words, the demonstration is perfected in the very reality of faith, in its substantial truth, from whence glows upon the mass of probabilities the ray of light which illumines them, and the unshakable certitude which binds them together.”

But this is not at all Newman’s meaning “in other words.” To affirm, as Loisy does, that it is faith which recognizes the argument from probabilities as the basis of certitude, is an illegitimate extension of Newman’s statement, which speaks merely of God’s cooperation with a well-intentioned inquirer in the examination of the multiple probable arguments, prior to faith. For Newman, the convergence of probabilities in itself, logically preceding faith, forms a sufficient argument for the rational certitude of that faith.

So even Newman’s words as they stand are a far cry from the inference Loisy draws from them. But Loisy has torn Newman’s statement from its context and inserted it in an altogether alien one. In this passage Newman had no intention of establishing the theory of the argument from convergent probabilities. He realized perfectly that his words were neither a theologically exact nor a theoretically precise statement of the argument. This is clear from the explanation which he prefaced to the passage in the Apologia, and which Loisy neglected to include in his quotation.

“Let it be recollected,” Newman warned, “that I am historically relating my state of mind, at the period of my life which I am surveying. I am not speaking theologically, nor have I any intention of going into controversy, or of defending myself; but speaking historically of what I held in 1843-4, I say…” (Then follow the words cited by Loisy.)13

This passage, therefore, is merely Newman’s historical relation of the state of his mind as an Anglican, of what he held and believed in the last years preceding his entrance into the Catholic Church. To call such a citation the “reproduction” of Newman’s “doctrine” on the manner in which the assent of faith may be considered to depend on probabilities is not the act of a sincere “disciple.”

The importance of context: Neglected both by Loisy and Newman’s critics

In addition to grafting on to Newman’s words a meaning quite alien, Loisy has thus misrepresented the Cardinal because he has violated the elementary rule against tearing statements from their context (which forbids a fortiori their use in a context totally different) and because he has failed, unwittingly or deliberately, to observe the second principle which we have been speaking of: that to understand the scope and significance of a passage from Newman we must keep in mind Newman’s purpose in writing those particular lines.

It might be objected that M. Loisy, in stating that he had “reproduced” Newman’s doctrine, did not mean that he had cited it directly, but that, in the course of his article, he had expressed it in his own words. A reading of the article in the Revue du clergé français is sufficient to refute this objection. Loisy’s theory, as expressed in his own words, was far distant from Newman’s, and entirely discordant with the final expression of Newman’s thought on the subject in the Grammar of Assent. As we do not wish to prolong this chapter unduly, we will let a significant sentence from Loisy’s article illustrate this essential discrepancy. We have seen the stress which Newman laid on the convergence of probabilities, which the intellect recognizes as an adequate foundation for certitude. But Loisy wrote:

“The possessor of the keenest mind, after having studied the bulkiest volumes of apologetics, can remain very undecided and perplexed, if he has consulted only his reason in its function of reasoning, and has limited himself to a critical examination of proofs, inasmuch as each particular proof leads only to a probable conclusion, which does not absolutely exclude the possibility of the opposing conclusion, and the decisive efficacy of the proofs does not depend entirely on their accumulation, which creates for the reason only an extreme probability, but on the intimate experience which is had of it, and on the vital relationship which is established between the searching soul and the truth which presents itself.14

Here is the key to the question. Loisy did not believe that probabilities, however cumulative, could lead to certitude, but only to an “extreme probability” which, however “extreme,” is still probability. And for him the efficacy of the proof does not lie in convergence, but in “intimate experience,” “vital relationship,” and so on.

It is not difficult to understand why, in the light of his unorthodox, subjectivist theory, the Modernist Alfred Loisy was condemned by the twenty-fifth proposition of Lamentabili; nor is it difficult to understand why Cardinal Newman was not.

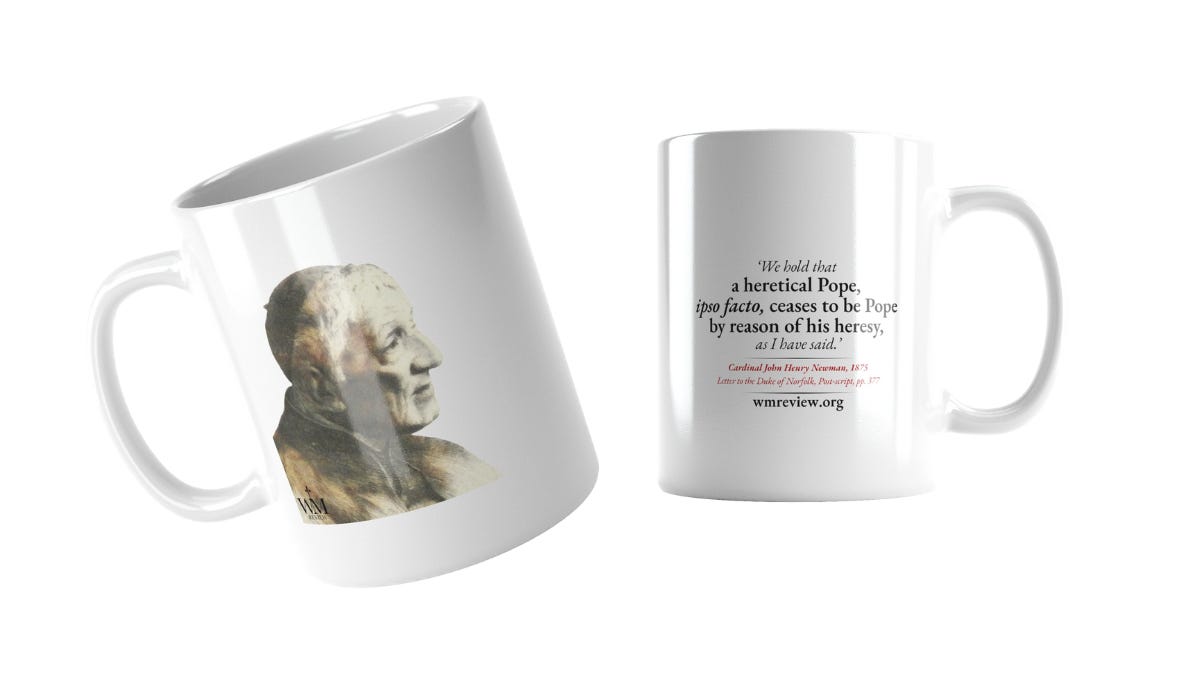

If you liked this article, why not enjoy it in mug form?

The perfect gift for anyone celebrating Leo XIV’s naming of Newman as a Doctor of the Church:

HELP KEEP THE WM REVIEW ONLINE WITH WM+!

As we expand The WM Review we would like to keep providing free articles for everyone.

Our work takes a lot of time and effort to produce. If you have benefitted from it please do consider supporting us financially.

A subscription gets you access to our exclusive WM+ material, and helps ensure that we can keep writing and sharing free material for all.

You can see what readers are saying over at our Testimonials page.

And you can visit The WM Review Shop for our ‘Lovely Mugs’ and more.

(We make our WM+ material freely available to clergy, priests and seminarians upon request. Please subscribe and reply to the email if this applies to you.)

Subscribe to WM+ now to make sure you always receive our material. Thank you!

Read Next:

Fr E.D. Benard – A Preface to Newman’s Theology

Plus, some highlights:

Follow on Twitter, YouTube and Telegram:

Unfortunately, the Bishop repeated a previous claim that Newman was “very tight” with the modernist Baron von Hügel, which is without foundation. The Baron was, in fact, “friends”(if the word is to be used so lightly) with all the leading men at the time – including Cardinal Manning, W.G. Ward and the future Popes Pius XI and Pius XII, prior to their elections.

Further, he was on considerably warmer terms with othees than Newman, whom he sharply criticised as “depressing” and – most importantly for the insinuations against the Cardinal – a “rigorist”. (Cf. The linked article.)

“Assensus fidei ultimo innititur in congerie probabilitatum.”

A.S.S., XL (1907), 473.

“XXV. The assent of faith rests ultimately on an accumulation of probabilities. This was Newman’s doctrine. I reproduced it in an article on the proofs and the economy of revelation, which I published in the Revue du clergé français of March 15, 1900. I doubt that the Sacred Congregation has gone back as far as this article. I doubt still more that the Congregation intended to condemn Newman. On the other hand, I do not find this proposition in my writings of the last few years. Either the Sacred Congregation has taken it from some disciple of Newman, or simply garnered it from the Question biblique au XXe siècle of M. Houtin, where my article is quoted (p. 75); or else it turned into a general proposition the words: ‘rational probabilities of this article of faith,’ which I used with regard to the divinity of Christ (Autour d’un petit livre, p. 129).”

Simples réflexions…, pp. 64 f. In late years Loisy renewed the charge (cf. Mémoires..., I, 48).

“There is no need of supposing (as some have done) that this twenty-fifth proposition of the decree Lamentabili represents Newman’s theory concerning the proof of the fact of revelation by ‘convergence of probabilities.’ Is it in any degree likely, moreover, that Cardinal Newman, and for a very defensible theory... should have been numbered among the partisans of this ‘synthesis of all heresies,’ as Pius X characterized Modernism?”

(S. Harent, article “Foi,” D.T.C., Vol. VI, col. 195).

The method of proof from convergent probabilities has been clearly set forth by H. Pinard de la Boullaye, S.J., in L’étude comparée des religions (Paris: Beauchesne, 1925), II, 388–424; and by A. Gardeil, O.P., in La crédibilité et l’apologétique (Paris: Gabalda et Cie., 1912), pp. 161–201. A brief, “popular” treatment of the same subject may be found in a fairly recent volume of apologetics by Joseph Falcon, S.M. (La crédibilité du dogme catholique [Paris: Emmanuel Vitte, 1933], pp. 113–15.) S. Harent in the article “Foi” which we have cited above, also gives an excellent outline of this method of proof. (D.T.C., Vol. VI, cols. 195–98.)

Cf., for example, G.A., pp. 320 f. (quoted in chap. 16 above); and G.A., pp. 319 f. (quoted below). S. Harent writes:

“Newman ne parle que de probabilités ‘convergentes’; la proposition 25 ne reproduit pas ce mot, capital dans sa théorie” (Harent, loc. cit.).

“Newman only speaks of ‘convergent’ probabilities; proposition 25 does not reproduce this word, which is central to his theory” (Harent, loc. cit.).

It is worth noting also that Newman attached a precise meaning to the word “probability.” By a “probability” he meant a fact, not necessarily of doubtful probative value, but merely not demonstrative (cf. above, chap. 13, A).

G.A., pp. 319 f.

Ibid., pp. 321 f.

Cf. Praelectiones dogmaticae (Freiburg: Herder, 3d ed., 1910), VIII, 131f.

Cf. supra, note 2 to this chapter. For a general analysis of the Modernist position regarding the assent of faith and the argument from probabilities, and a comparison, along very broad lines, with Newman’s theory, the reader may consult S. Harent, “Foi,” D.T.C., Vol. VI, cols. 194 f.

“La vraie religion est faite pour être connue, expérimentée, vécue, et cette expérience intime en a toujours été la véritable demonstration, variable dans son expression logique selon les temps et même les personnes, certaine pour tous ceux qui croient, c’est à dire qui, voyant d’assez près la religion pour la bien connaître en elle-même et par rapport à eux, ont le courage d’y adhérer volontairement… La demonstration la plus savante ne change rien à ces conditions essentielles de la foi. Voici ce qu’en écrit le cardinal Newman:

[Here Loisy gives the French translation of the text from pages 199-200 of the Apologia which we have repeated above].

En d’autres termes, la démonstration s’achève dans la réalité même de la foi, dans sa vérité substantielle, d’où rejaillit sur la masse des probabilités le rayon qui les éclaire, la vie qui les anime et la certitude inébranlable qui les rassemble. La foi, disons-le encore, ne laisse pas d’être profondément raisonnable, bien qu’elle ne soit pas affaire de spéculation rationnelle, mais sa haute raison n’apparait en toute évidence qu’à ceux qui veulent sincèrement la connaître et qui n’ont pas peur de la vérité. Rien n’empêche les ignorants d’y réussir à leur manière aussi bien que les savants, sans tant de recherches et de discussions.

Pour être ainsi comprise, la certitude de la révélation n’est pas diminuée; elle est ramenée à son véritable caractère, qui est d’être une certitude de foi et non une certitude scientifique”

(Revue du clergé français, Vol. XXII, no. 128 [March 15, 1900], pp. 142 f.).

Apo., p. 199

“Mais l’esprit le plus clairvoyant, après avoir étudié les plus gros livres d’apologétique, peut être encore fort indécis et perplexe, s’il n’a consulté que sa raison raisonnante, et s’il a borné son examen à la critique des preuves, attendu que chaque preuve particulière n’aboutit qu’à une conclusion probable, laquelle n’exclut pas absolument la possibilité de la conclusion opposée, et que l’efficacité décisive des preuves ne dépend pas non plus tout à fait de leur accumulation, qui ne crée encore pour la raison qu’une extrême probabilité, mais de l’expérience intime qui en est faite et du rapport vital qui s’établit entre l’âme qui cherche et la vérité qui s’offre” (Revue du clergé français, Vol. XXII, no. 128 [March 15, 1900], pp. 140 f.).

The “certitude” resulting from this “intimate experience” and “vital relationship” seems to be what Loisy had in mind when he wrote, some years later, of the “moral certitude” being by the “ensemble” of probabilities (cf. Simples réflexions… p. 70).

Blessings and appreciation from Sydney Australia.